I had not wanted to live in an expat community during this year in Morocco, but as I trudge up the hill toward the suq, I begin to see some advantages. I am wearing a pair of linen trousers and a linen shirt, both of which belong to Lynn-the-textiles-expert-who-is-leaving-for-Doha. I still don’t know Lynn’s last name or even her email, but over the next few months, I will be wearing her clothes, drinking out of her mug, eating her spices. Channeling Lynn. At the same time, I will be regretting my failure to record her impromptu lecture-demonstration on Moroccan rugs and textiles.

Lynn’s first career was as a spinner and knitter in the United States, and she achieved national recognition for her work. When I came by to look at her rugs and her give-aways, she was packing up some of the journals that featured her work. She showed me some exquisitely fine hand-spun lace knitting she had done, and (like all true spinners) dismissed my inability to work with a drop spindle. “It’s easy—and so convenient!” Convenient, yes; easy, for some. Give me a wheel any day.

“What brought you to Morocco?” I asked, but I should have known. It’s an old sad story. Textile artists, like many other artists, can’t survive on their work. When Lynn realized that even the top people in her field could make a living only by traveling and giving workshops six months out of the year, she decided she needed a day job—and that day job, in academic support, has taken her on a twelve-year odyssey around the globe, with a two-year residence in Morocco.

I think about Lynn, not only as I wear her clothes, but as I look around at her rugs, scattered through our house. We have an exquisitely soft, hand-spun, naturally colored brown-and-gray striped piece that I can’t bear to put on the floor. “It could be a couverture (bed covering) or a rug,” Lynn acknowledged, and I imagine huddling under its fibers in the cold winter everyone warns us about.

Similar in coloring, but rougher to the touch is a goat’s wool rug I’ve put under my work table. “Walk on it and the fibers will become shiny,” Lynn advised.

In the living room, we have a large rug, striped red, purple, blue, with one thin slice of bright orange.

“Those will be synthetic dyes, probably, because the orange is not available with the natural dyes. That stripe, it constitutes a signature,” Lynn told me. “The way it stands out, calls attention to itself: it’s a mark of individuality, idiosyncracy.”

On the other side of the living room, there’s a slightly older piece, hand-spun, all in red, with wonderful variations in color; the red comes from cochineal—crushed insect shells. Remember the insects that live on Opuntia–prickly pear cactus?

There are rugs I didn’t buy, because we felt so short of cash: one rug that had a wonderful patched hole in it, from serving as part of a Berber tent; another where the colors were too bright for my taste. There were other rugs Lynn wasn’t selling—she felt obliged to return them to the person she had bought them from, because she had had to work so hard to persuade the original owner to part with them. There was the immense “aliens” rug—yellow and brown with other accents, full of humanoid figures. “The prohibition on reproducing the human figure comes from Arab culture, not Berber society,” Lynn noted. “But what would you do with this piece? It needs to be hung in some monumental space.” She described another rug as being “woven with time.” The weaver used the same dye but left the rug exposed to the sun during the weaving process so that some of the coloring would fade, creating a two-tone pattern.

Lynn was particularly interested in a transitional moment in bouchereite: rag rugs produced by Imazighen (Berber) women. “There’s this explosion in creativity,” Lynn asserted. “All of a sudden, there were these industrial scraps available, and they were cheap, and so the sky was the limit. It wasn’t like working with wool that you had to shear and clean and card and spin. The rags must have felt like a windfall, a nearly free resource.” In her collection of bouchereite, Lynn tracked the way weavers would create a sense of motion in their work: the blue river, she called one piece, for the meanderings of blue rags down the middle of the pattern.

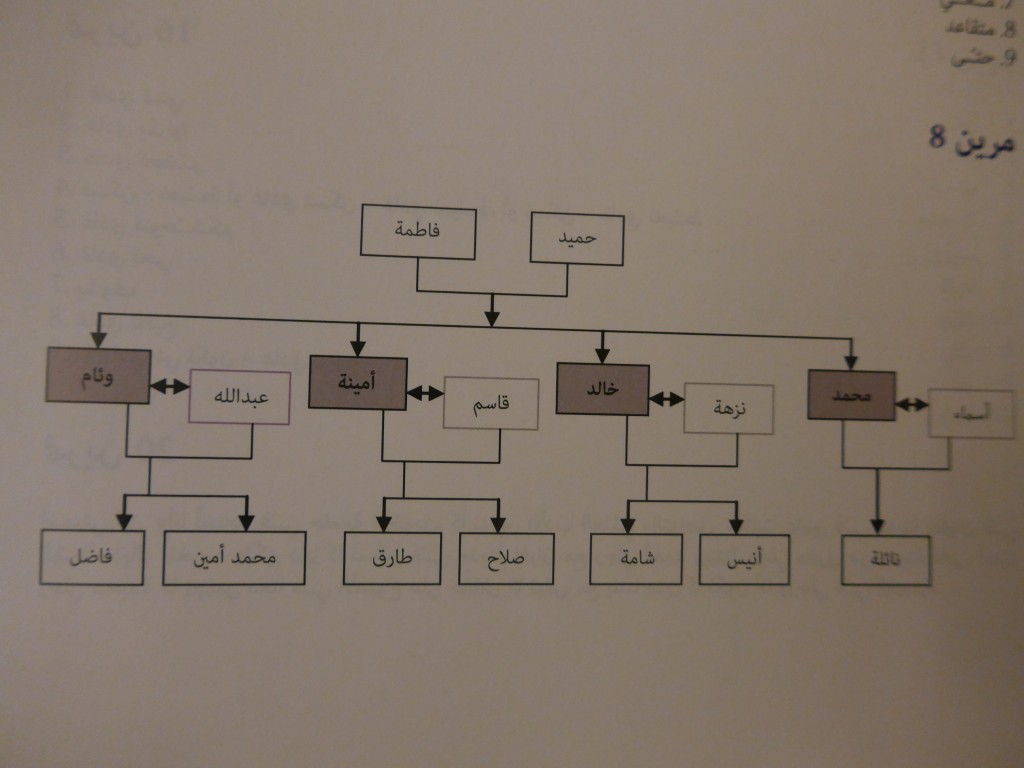

Another piece that she called the red trellis showcases the traditional diamond pattern that Lynn insisted was vaginal—“I have a picture of this old weaver woman, her knees wide, holding open her vagina: it’s a classic diamond, I’m telling you”—and a recording of lineage, a weaver recording her family back through her mother and her mother’s mother.

Lynn prized the oddities, the idiosyncrasies in rugs: “These are the places where you see a woman, weaving in isolation, making a statement, creating something personal. The workshops that have been set up more recently make women’s lives much better by offering them a community in which to work, and providing a clearer market for their goods, but there’s a loss in terms of creativity. Instead of a single woman making her individual decisions, there are set patterns that are taught and maintained. They’re all good—I just happen to like seeing the individual weaver at work.” But the transitional moment passes. “After that initial explosion, the spark goes out,” Lynn said. “It’s as if the women suddenly looked up and recognized what they were working with: garbage. Call it recycling, repurposing, call it what you want, but it’s the same old story: you don’t get any real resources after all.” Now there’s a Marxist-feminist analysis: base and superstructure as seen through the lens of gender.

Someday, once we acquire a car and my Darija improves, perhaps we’ll go rug-shopping for ourselves, for the education of it. In the meantime, Lynn’s rugs have moved into Omar’s house, and together they offer a beautiful, comfortable back-drop to our lives here. And that’s even before considering the linen towels, sheets, and pillowcases Lynn gave me: suq finds that I hope to replicate, if my fingers can ever become as knowing as Lynn’s, as quick to feel the differences among linen, cotton, and synthetics. “This piece,” she said, showing me a prize she would take with her to Doha, “came from Hungary: you can tell by the design. I love to see these fabrics travel, to imagine the route that would bring them to this little suq in Ifrane.” Fabrics and people, wandering through this landscape.

Omar’s house is unusual in several respects: it separates public areas (ground floor) and private sleeping areas (upper floor) instead of mixing them together; it has a well-equipped kitchen, including an oven (!) and a microwave;

Omar’s house is unusual in several respects: it separates public areas (ground floor) and private sleeping areas (upper floor) instead of mixing them together; it has a well-equipped kitchen, including an oven (!) and a microwave;

and it’s nicely furnished in a mixture of Moroccan and French styles.

and it’s nicely furnished in a mixture of Moroccan and French styles.