is a whole lot harder than you might think–but also kind of obsessively compelling.

Here, Adam is trying to teach me how to see the patterns, the grids, underlying biomorphic designs in the Al-Attarine, but really, it’s a bit of a hopeless task. Take this panel, for instance:

I thought this little creature with eyes should be the repeating motif. So adorable!

Oops. Probably that’s not meant to be a creature at all. The double loop at the center of the image below (and placed in the four corners of the design as well) is a better unit to focus on for tracking the extension and tessellation of the image. See the grid that comes into focus around that repeated double loop? You’re looking for a rhomb, a dynamic (or diagonal) square shape that repeats both vertically and horizontally.

And now can you see why some of us might find this process challenging?

The plaster carvers would have created a cardboard (in medieval times, stiff paper or vellum) template to draw the design grid on the fresh, damp plaster. Then they would have “pumiced” the shape through the template, leaving black pigment on the plaster–and then they would have used fine, sharp tools to carve out the plaster into these shapes.

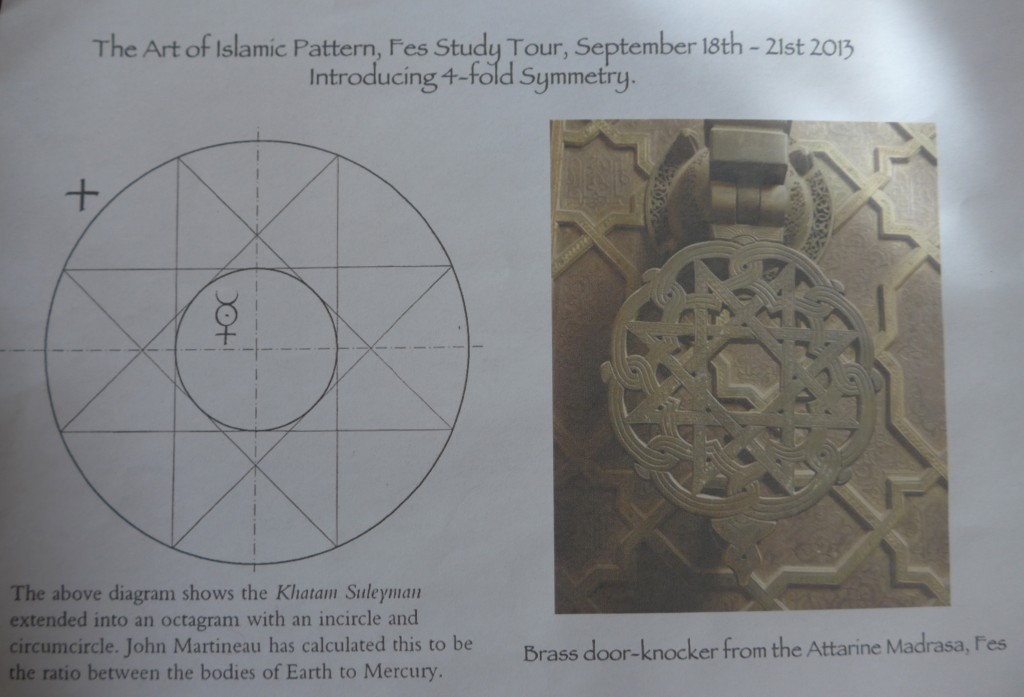

Adam has carefully parsed pattern after pattern for us. Here’s just one example: the stunning door and knocker at the Al-Attarine. The knocker itself is a khatam (static square plus diagonal square extended out from it), extended further into an eight-pointed star…

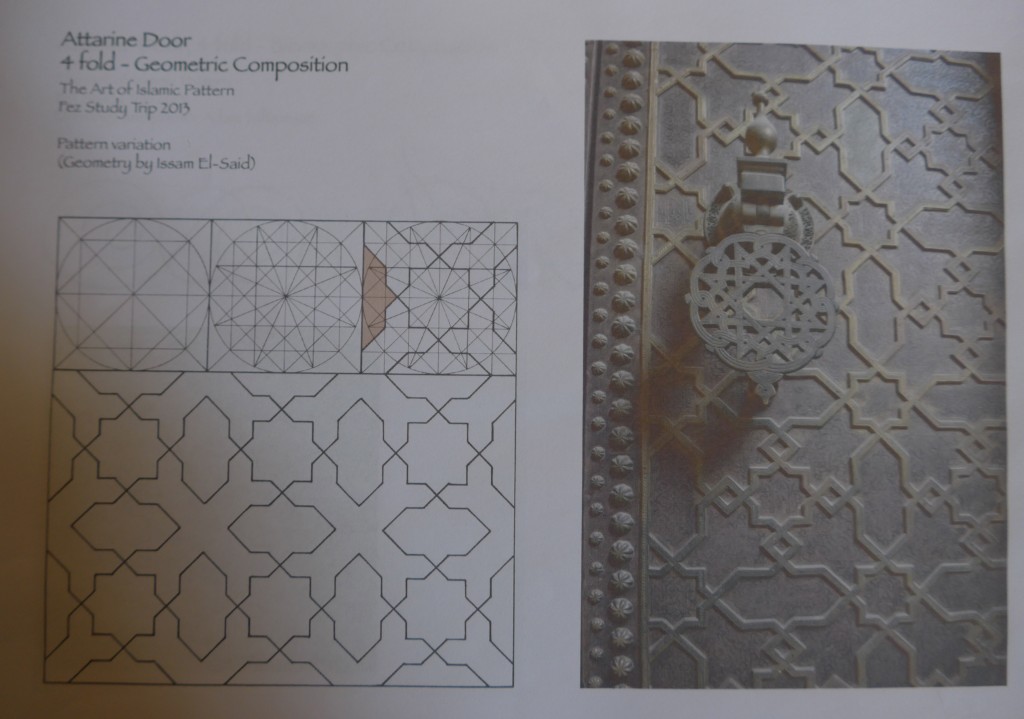

What about the door behind the knocker? It’s almost like a variation on my beloved “breath of the compassionate” pattern: khatams, some surrounded by four dynamic squares, diagonal crosses, plus safts (or petals) to fill out the pattern.

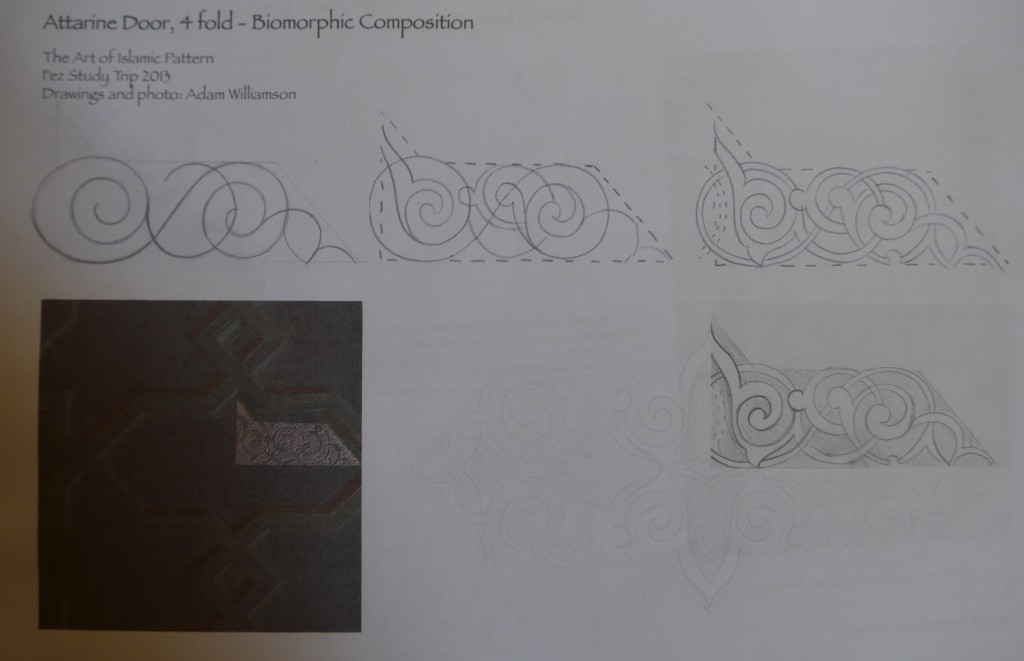

Adam takes the analysis one step further, drawing out the incredibly fine (and faint) biomorphic design traced within each of those large safts:

Isn’t this amazing? First, the painstaking detail of the design–and then the painstaking, even meditative recreation of that design.

Not to mention the painstaking correction of student errors in attempts to further replicate those designs…

Geometry and generation:

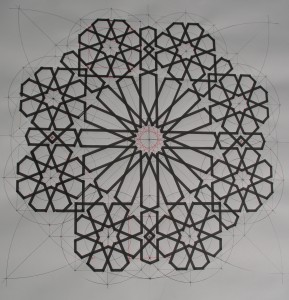

On the geometrical side, meanwhile, Richard (having walked us through the many stages of creating a 12-fold rosette among other patterns), asks us to think about the shapes that can be generated from a khatam. Some of us understand the question well enough to sketch some possible shapes. (Tip: think about cutting pieces out of a khatam or possibly extending corners out to make a new shape.)

Richard chooses the most useful propositions and has us cut out templates for creating watercolor zellij–paper versions of the cut tiles used in Maghrebi mosaics.

We paint and cut out the shapes, and then we play with different arrangements, from small to large:

Some principles for productive play: 1) think about the white space; 2) join shapes point to point, not side to side; 3) follow straight lines to extend patterns; 4) be intentional about color patterns; 5) share your pieces; 6) have fun!

Islamic art: Islamic carvers from Egypt, Persia, and Spain are renowned for their skills and attention to details. For fittings and furniture, they executed the highest level of decorations and paneling. The most delicate and elaborate woodwork by Islamic carvers is found in mosques and private homes of individuals in Cairo and Damascus. The most common style was to cover the surface with an intricate lacing pattern. These patterns were formed using ribs. The spaces between the ribs would then be filled with wood carved with foliage. They used different wood types to emphasize the art and make it more appealing. Arabs are the most prominent of carving art in flat surfaces. The appreciation of surfaces and lines is well displayed in a gate mosque in Cairo.