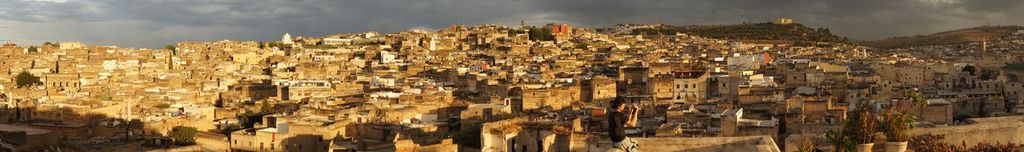

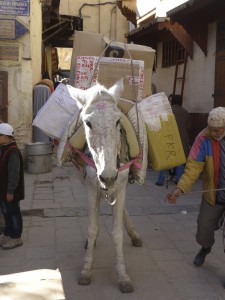

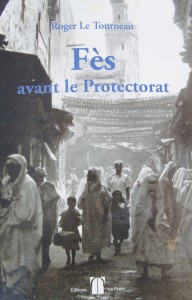

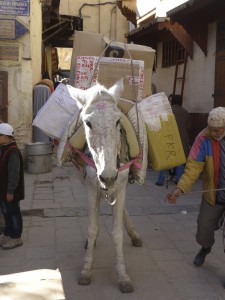

Narrowly defined, a palimpsest is a piece of writing material that’s been used more than once, so that earlier writing has been erased or covered, but traces of that previous text still remain. Fès is like that, with medieval elements peeking through its modern modes of functioning. The two time periods intersect most obviously, perhaps, in the fact that the both the UPS guy and the Coca Cola truck are… donkeys.

The cry of the medina: Andak! Balak! Look out: donkey coming through!

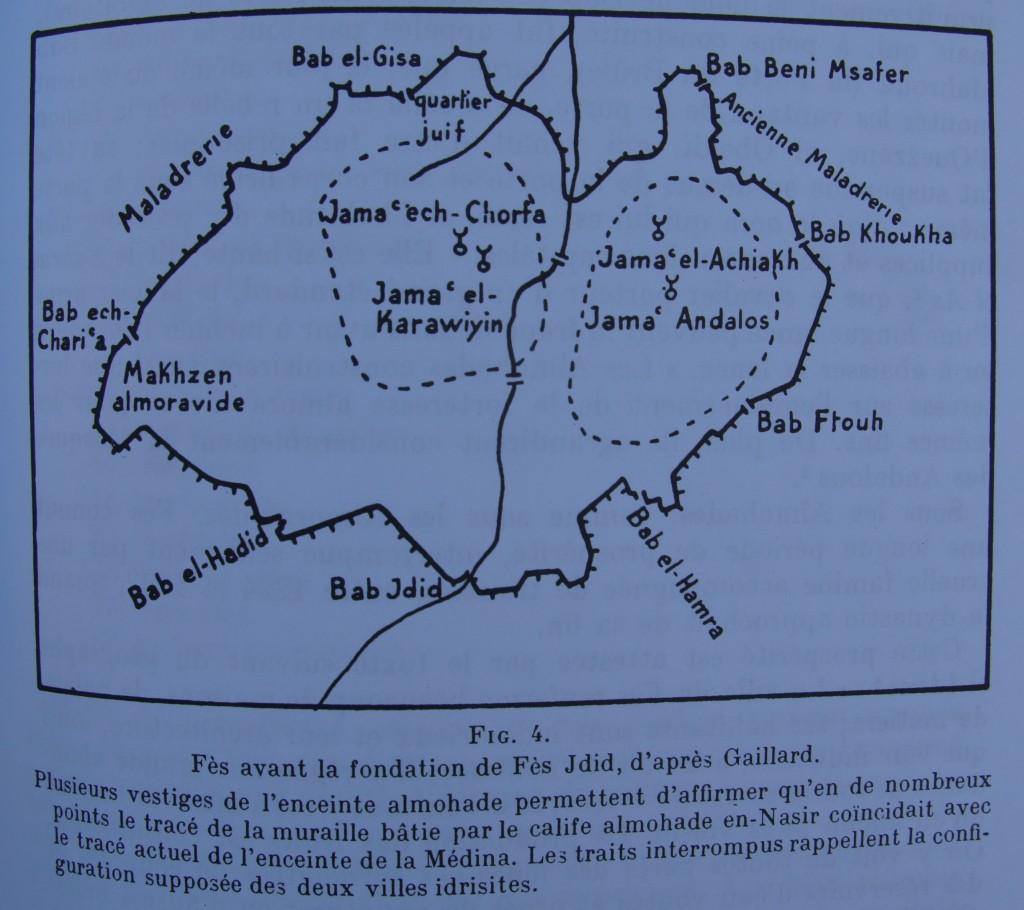

Can we recreate the previous writing of this palimpsest? Maybe not. Who really knows what the oldest layer of Fès (the Idrissid period) looks like?

Alla, Iraqi-Moroccan owner of the guesthouse Dar Seffarine and an architect specializing in Fès restorations, focuses on some basic elements. “Fès had water and materials for building. Mud houses had existed here for many many years, but with the major construction of the city in the 8th century, they imported architectural principles from the East.”

Water:

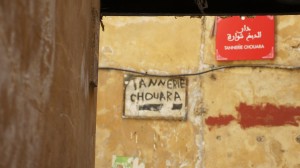

Some of Fès’s rivers are still visible, channeled through cement, but not yet covered over. The river still serves (and suffers from) the crafts practiced through the city: here, the tannery…

and, hidden under the bridge, some small-scale metalworking.

Materials for building:

The foundational material is “medlouk” (I think this is the regional word for what Marrakshis call tadelakt): 50% lime and 50% sand. The lime (chaux in French) is composed of limestone, marble, and shells; Romans similarly used limestone and volcanic rock to make a kind of concrete.

Medlouk takes its form from the “lime cycle,” connecting the architecture of this area with the limestone of the landscape. What’s the lime cycle? you ask. (Well, let’s pretend you want to know.) When heat is added to limestone, a chemical reaction occurs: CaCO3 turns into CaO (quicklime) plus CO2. When you add water to quicklime, you get slaked lime: CaO + H20 = Ca (OH)2. Expose slaked lime to air and it will slowly react with carbon dioxide to form calcium carbonate or limestone, plus water: CaCO3 + H2O. So here’s one way to think about all this: the buildings in Fès are made out of limestone–mined, fired, and reconstructed limestone. Its architecture is recycled rock–mineral shaped and transformed by humans, but still rock–almost a living, breathing stone.

David Amster, a resident of the medina and a passionate advocate for this traditional building material, says lime mortar is “like a solid sponge.” Because it’s porous, it insulates well: medlouk lets moisture escape. It’s also oddly flexible: in the slaking and the curing process, molecules themselves stretch. Medlouk distributes the weight of the walls–otherwise, the stone at the bottom of a tall Fassi structure would explode from the weight of the upper (stone) stories. In case of seismic activity, medlouk has some “give” to it; if it cracks, it can heal itself. By contrast, cement sets fast but it is brittle–and unlike medlouk, cement is not porous, so it traps moisture.

Cement covered with more traditional plaster

David leads our study tour on a walk through the medina, working to disprove the myth that Fassi exteriors were unimportant in comparison with interiors. David insists that the original façades were beautiful–though he grants that the interiors were still more beautiful. The highlights of our walk touch on elements that could have come from many different periods of Fès’s history, though they stress the basic elements of water and building materials.

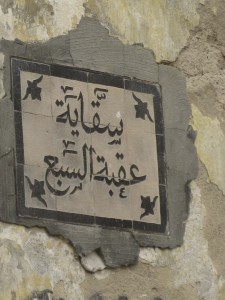

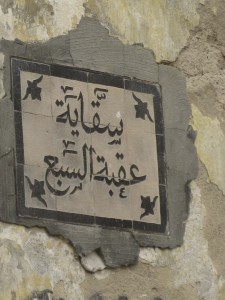

Until recently, water in Fès was free, available through an ancient system of fountains and pipes. A siqaya is a public fountain, built by a wealthy homeowner as a public benefit (the plaque on the right announces the name of this siqaya:

This particular siqaya shows the distance between earlier craftsmanship and more recent repairs:

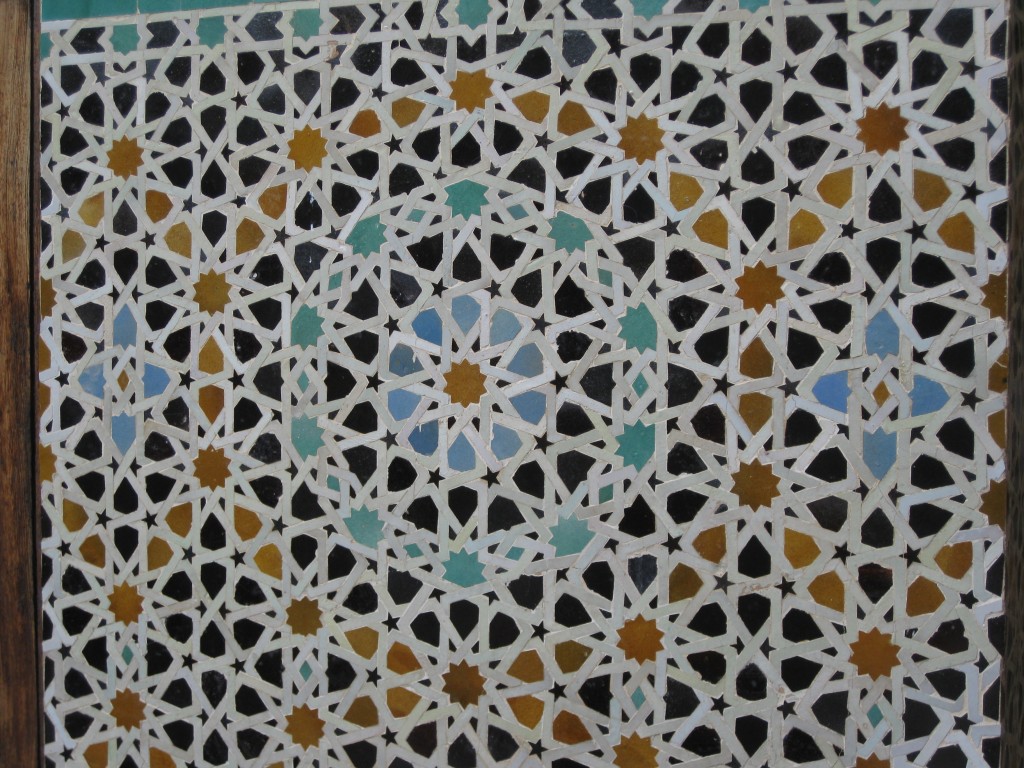

The left shows the original zellij; the right shows the relatively shoddy repair work.

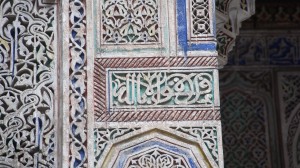

The black calligraphy around the fountain is produced by glazing the tiles black, then carving out the negative space around the shapes and letters. Once again, the recent repair work (visible in the right hand image, in the odd little alien-esque figures) seems laughably poor in comparison with the original.

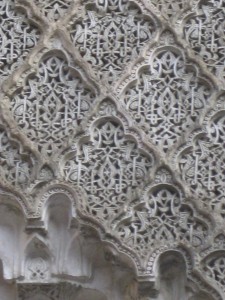

Medlouk as an exterior surface has a certain austere beauty, but it could be decorated by pressing wire into the plaster surface before it dries, as in the example of this carefully remodeled house, Al Adir:

Or this more extravagant design:

Below is another design pattern, with bricks visible below. Bricks were expensive, so they would have been left exposed (while stone would be entirely covered with medlouk):

Carved wooden surfaces offer another medium for elaboration: amazingly detailed even when discoloured by age, and half-hidden by an unattractive street lamp.

Other arches sport small decorative zellij and calligraphy at the keystone:

David persuaded a friend to restore a wall within the medina to the standard he thinks would have obtained during original construction in ancient Fès : exposed bricks, interesting design, elegant medlouk. Imagine an entire medina like this:

Architectural principles from the east:

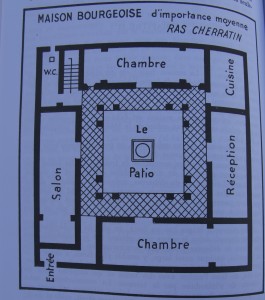

After water and building materials comes architectural principles. Alla describes simple shapes, responsive to the environment. Lines: “Follow the breeze. The old street plans are a diagram of the movement of air. The plan of the city sent all roads to the north. But then in the summer came sandstorms, and they moved some of the streets to block the storms.” Circles: “The medina is an organic form. At the center of each neighborhood, there is a mosque. Around the edges, the free façade of that mosque, some trading develops into a suq. Around the suq, houses are built; around the houses, gardens; around the entire area, a wall.”

This map from skyscrapercity.com shows some of the street layouts defining Fès today, though most of the derbs or residential streets don’t appear. The rivers that watered the ancient city are still visible at the margins.

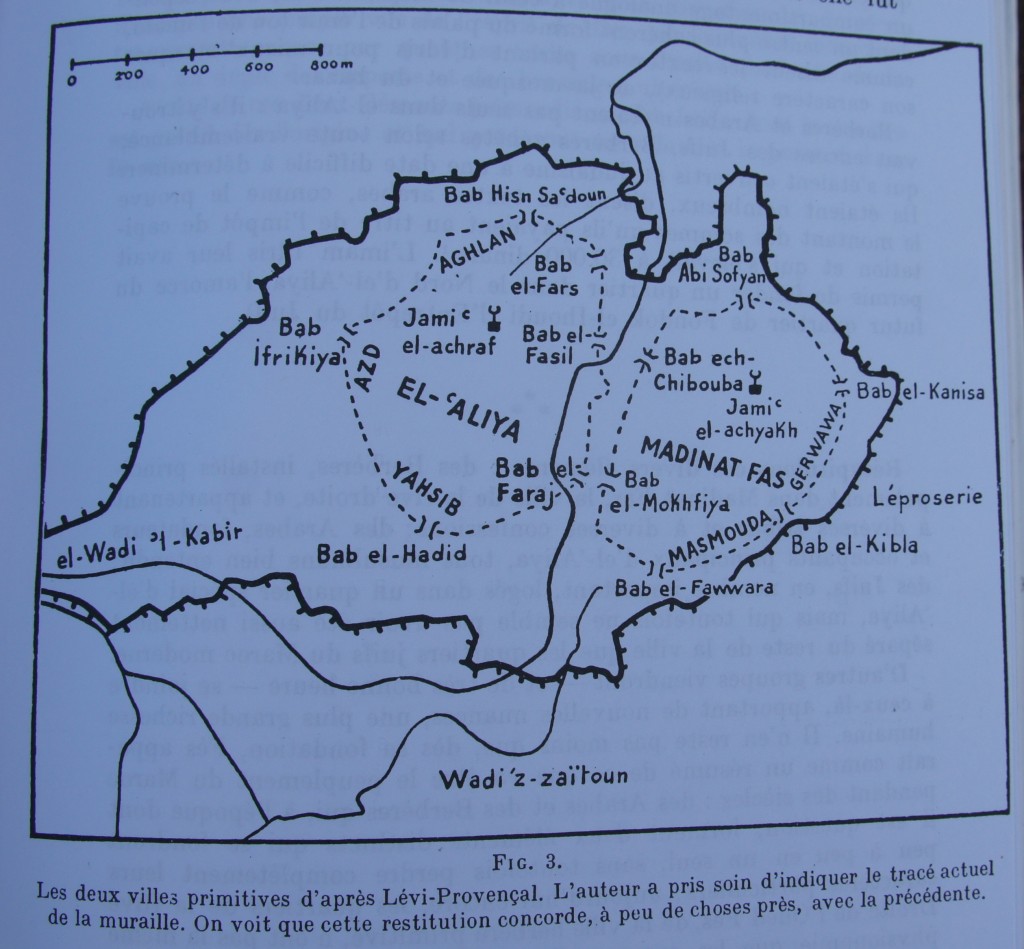

But descriptions of Idrissid Fès, according to Wikipedia, describe a rural town, a far cry from the sophisticated cities of Al-Andalus (Moorish Spain) and Ifriquia (Algeria/Tunis). Imagine two small centers, with open areas surrounding them.

The Almoravids

After Idrissid Fès comes Almoravid Fès. In 1070, the Almoravid Ibn Tashfin conquered Fès and transformed its two rural towns into a single city. Walls separating Medinat Fès from Al-Aliya were taken down, bridges were built over the river, and a new wall was built to connect the two centers. The Qarawiyyin mosque was expanded and renovated in 1134-43 and Fès became a famous center for Maliki legal scholarship. (The Malekite school is one of four major traditions within Sunni Islam: more details coming on a historical reference page.)

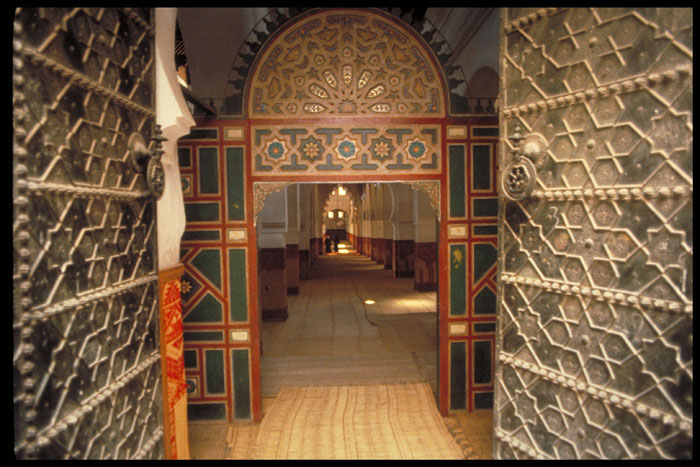

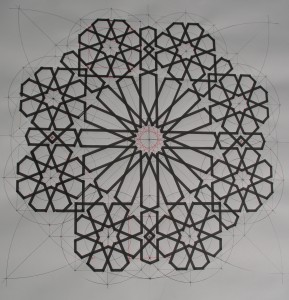

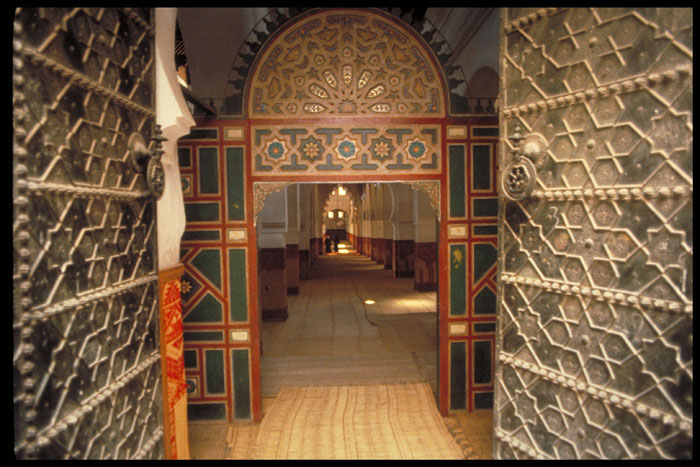

Image from Walter B. Denny Islamic Art Photographs, University of Washington Digital Collection

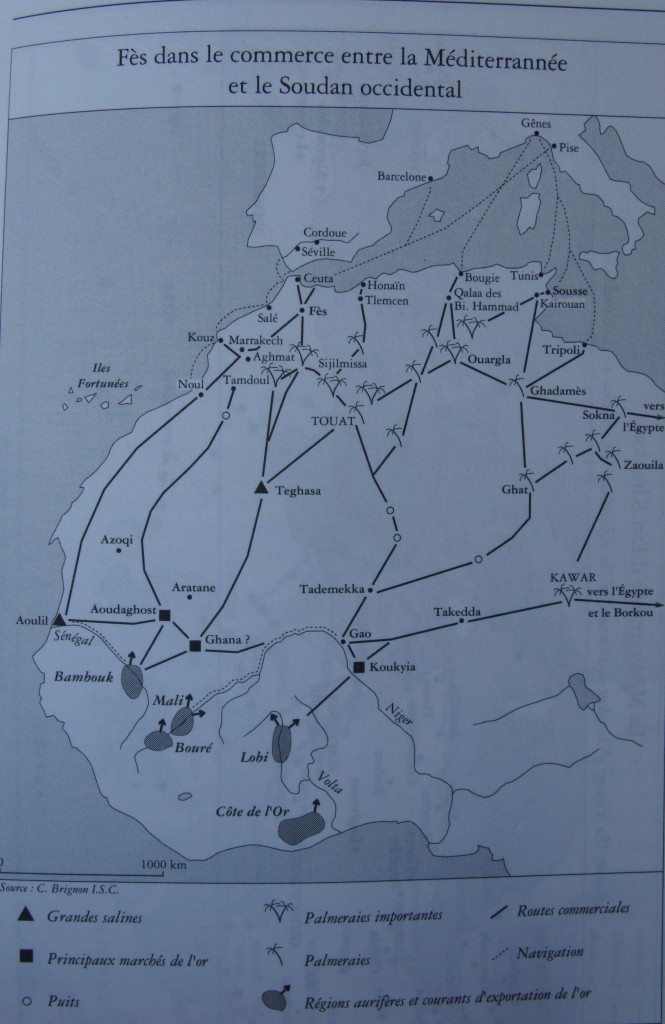

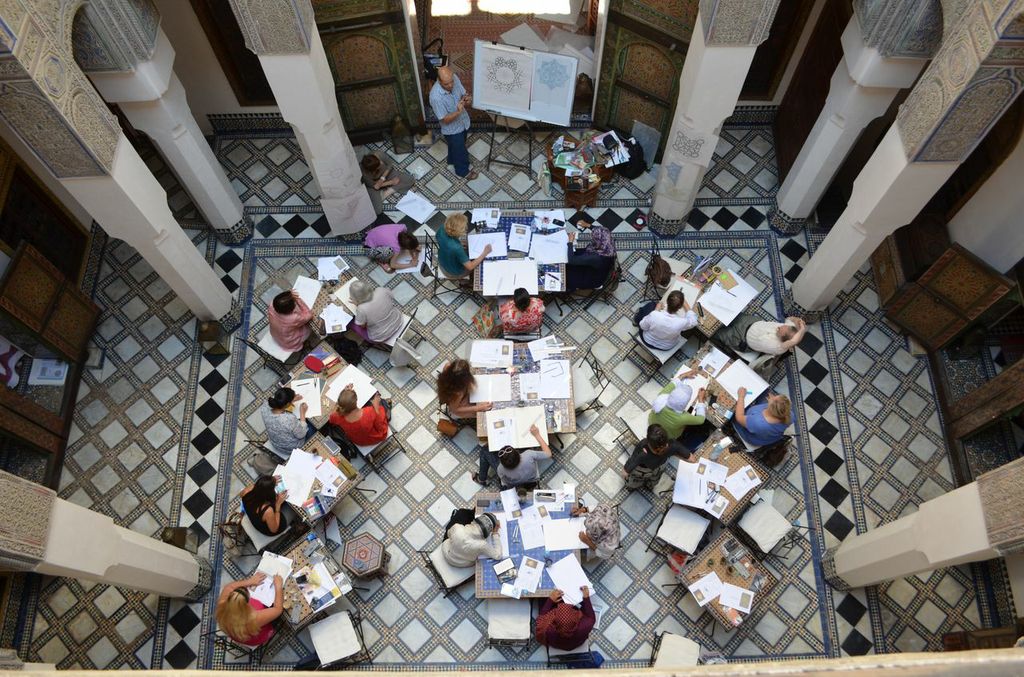

The next dynasty, the Almohads (1121-1269), broke down the old Idrissid city walls and constructed new walls which still define the outer boundaries of Fes el Bali, the old city. Under the Almohads, Fès became a major center for trade, the largest city in the world in the years 1170-80. Part of this merchant city’s structure were the funduqs that served as hostels for traveling merchants, with an open courtyard for pack animals surrounded by artisan’s workshops on the groundfloor, with rented rooms on the floors above.

The magnificently restored funduq now serving as the Nejjarine Museum of wooden arts and crafts was built much later (1711), but it gives a (grander) sense of what the earlier funduqs might have been like.

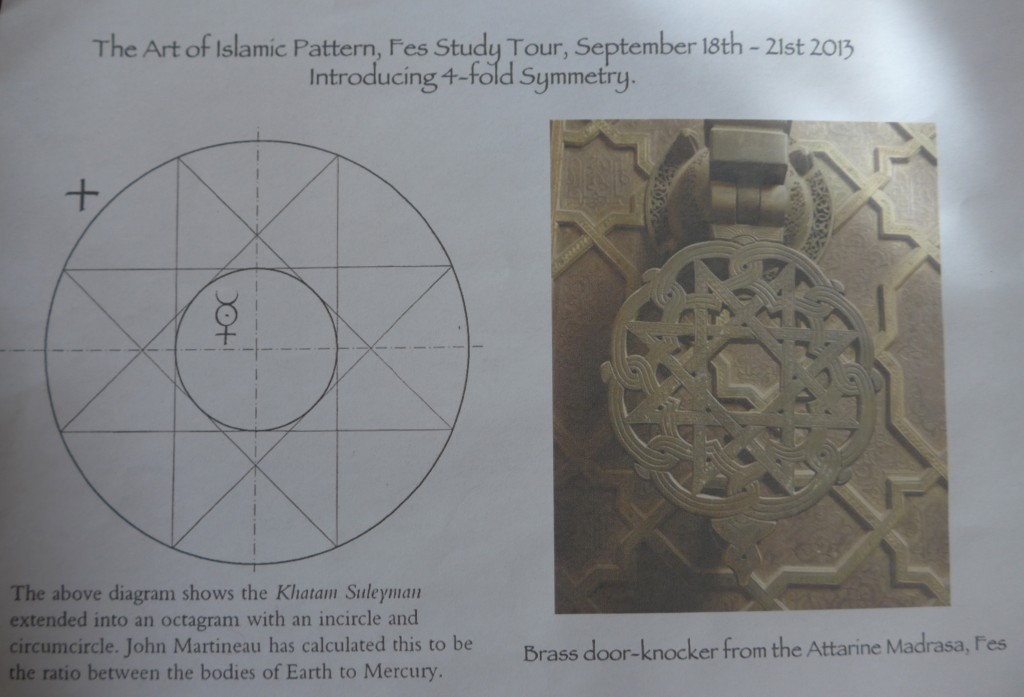

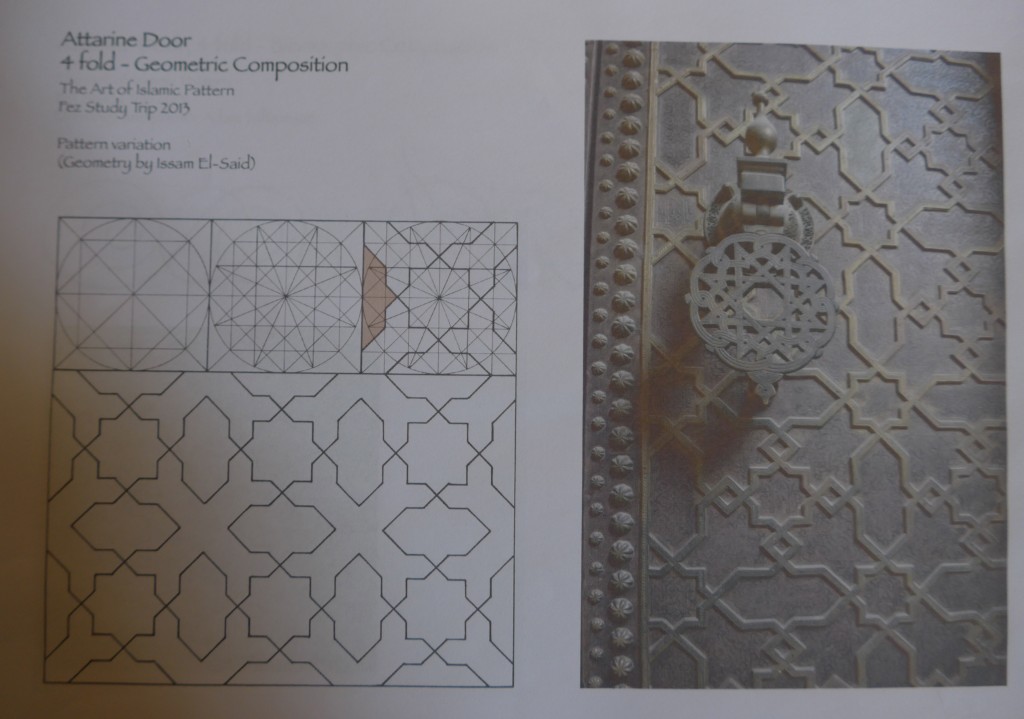

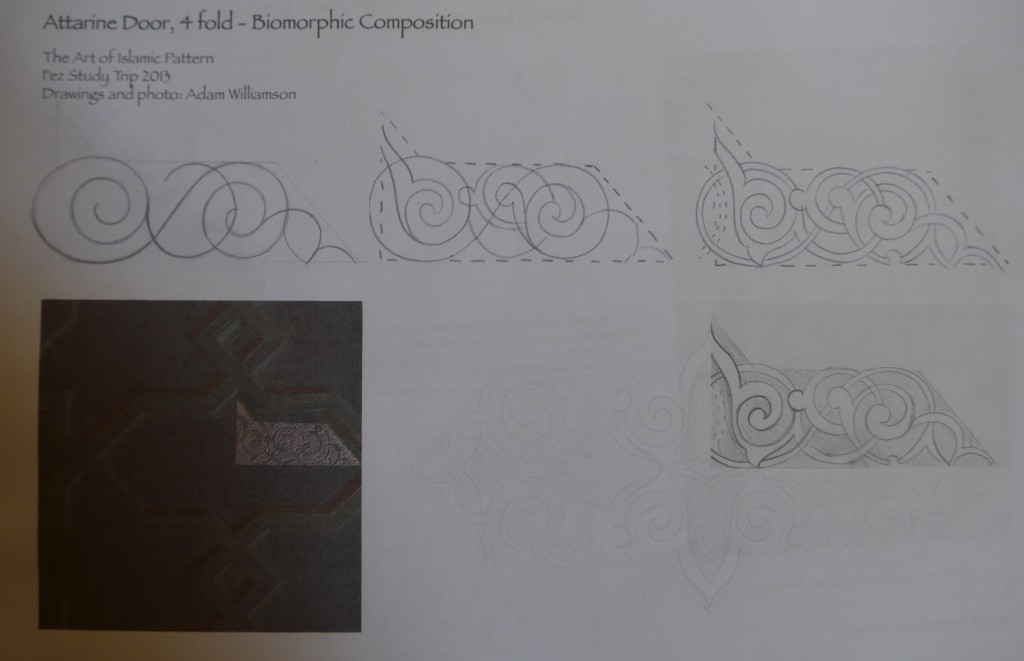

Still, I think everyone would agree that the Marinid dynasty (1244-1465) left the most extravagant visual effects, particularly in medersas like the Bou Inania and the Attarine.

Bou Inania

These architectural gems are so complicated, though, that they deserve a post or more just for themselves. Coming up soon!

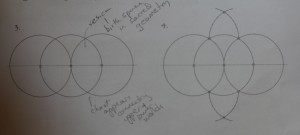

starts out something like this:

starts out something like this:

Sama straightening out one of my many confusions…

Sama straightening out one of my many confusions…

Notice the important rivers (wadis or oueds) running between and around the two towns

Notice the important rivers (wadis or oueds) running between and around the two towns