OK, this is a geeky post, with maps and dates. But where else are you going to find these kinds of details, right? [Correction: now you can find a much fuller introduction to Fès on my friend Eric Ross’s blog at http://ericrossacademic.wordpress.com/2013/10/11/presenting-moroccos-imperial-cities/.] Still, I have to get this out of my system before I move onto all the photos of the highly photogenic Fez medina….

Morocco’s four imperial cities—Fez, Marrakech, Meknes, and Rabat—survive with one foot in the present and one in the past in part because they shared the status of “imperial city” with one another for many years.

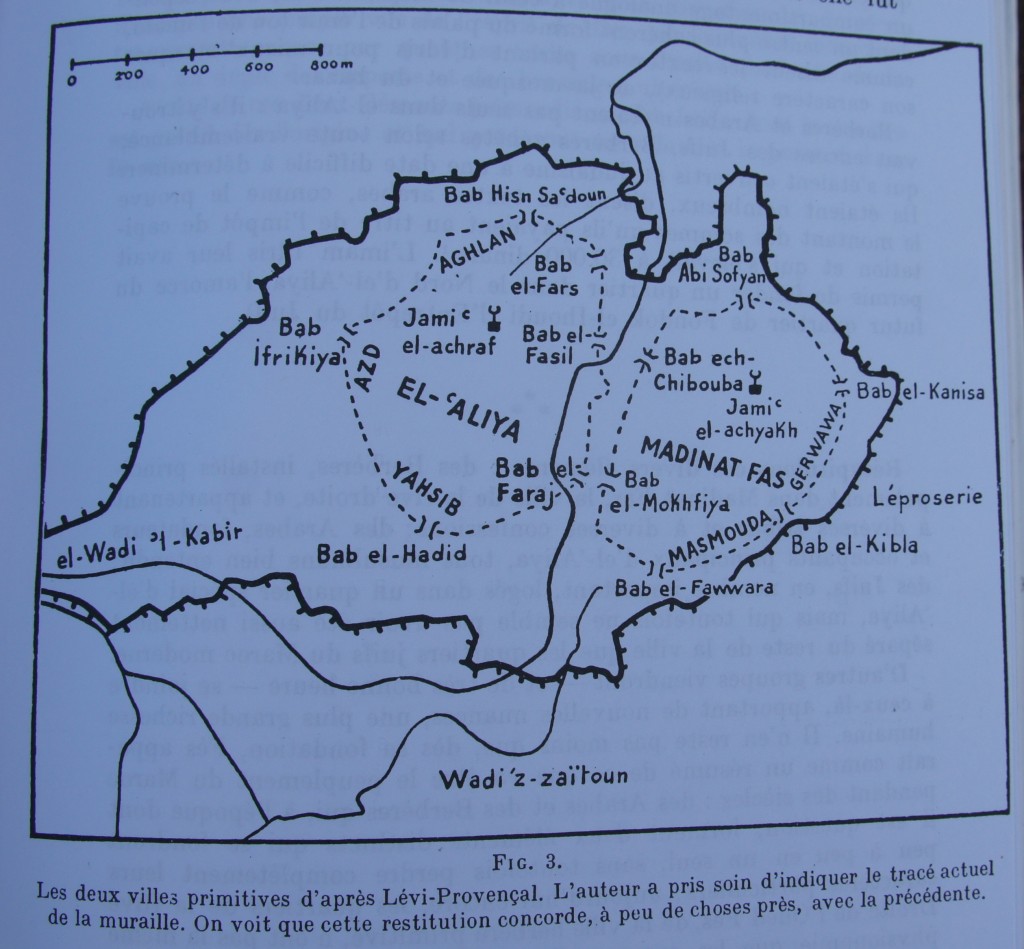

Fez was founded as Morocco’s first imperial city by the first Moroccan dynasty, the Idrissids. Actually, it was founded as two separate cities. First, Idris I founded “Medinat Fas” in 789; then, Idriss II founded Al-Aliyah twenty years later (809).

Notice the important rivers (wadis or oueds) running between and around the two towns

Notice the important rivers (wadis or oueds) running between and around the two towns

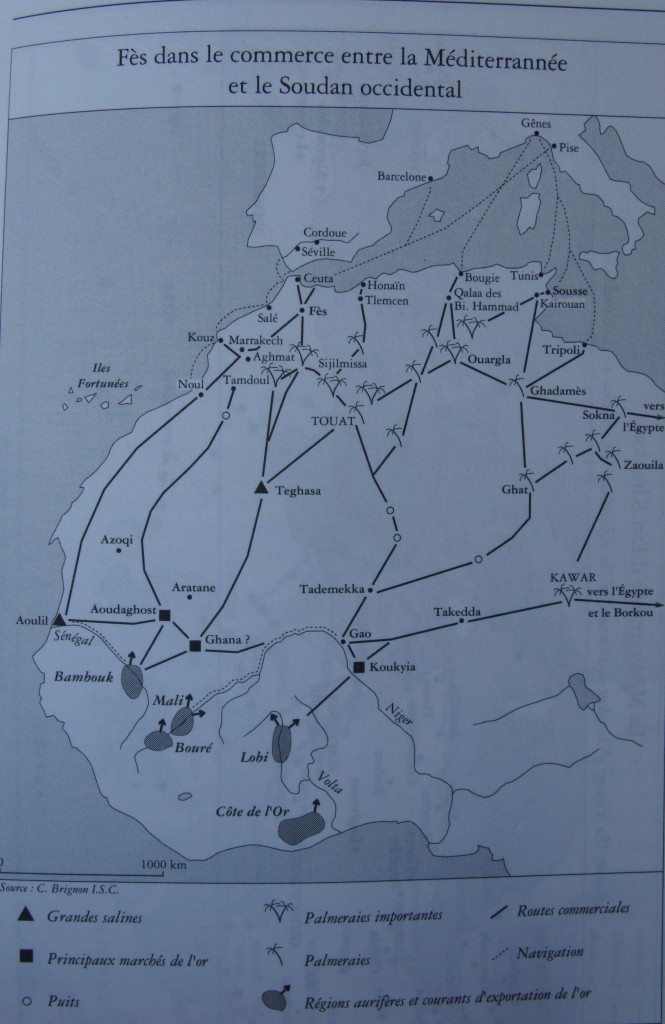

The two towns remained distinct, separately walled, for centuries. In a bid to gain greater independence from his local Berber protectors, Idriss II, identifying as an Arab, welcomed two waves of Arab immigration into the city of Fez: first, 800 refugee families from Cordoba settled in Medinat Fas in 818; second, 2000 refugee families from Kairouan settled in Al-Aliyah in 824. (You can find both cities on the second map below, the one with trade routes: Cordoba in Al-Andalus [modern day Spain], and Kairouan below Tunis, near Sousse.)

Imagine, if you can, 2000 families moving across the top of Africa en masse–or 800 families crossing the Straits of Gibraltar. What chaos that must have been! Imagine 2800 families–maybe 10,000 people? more?–settling into two tiny towns of mud buildings and trying to build a city big enough to hold them. The pilgrims landing on Plymouth Rock look like pretty small potatoes in comparison.)

Imagine, if you can, 2000 families moving across the top of Africa en masse–or 800 families crossing the Straits of Gibraltar. What chaos that must have been! Imagine 2800 families–maybe 10,000 people? more?–settling into two tiny towns of mud buildings and trying to build a city big enough to hold them. The pilgrims landing on Plymouth Rock look like pretty small potatoes in comparison.)

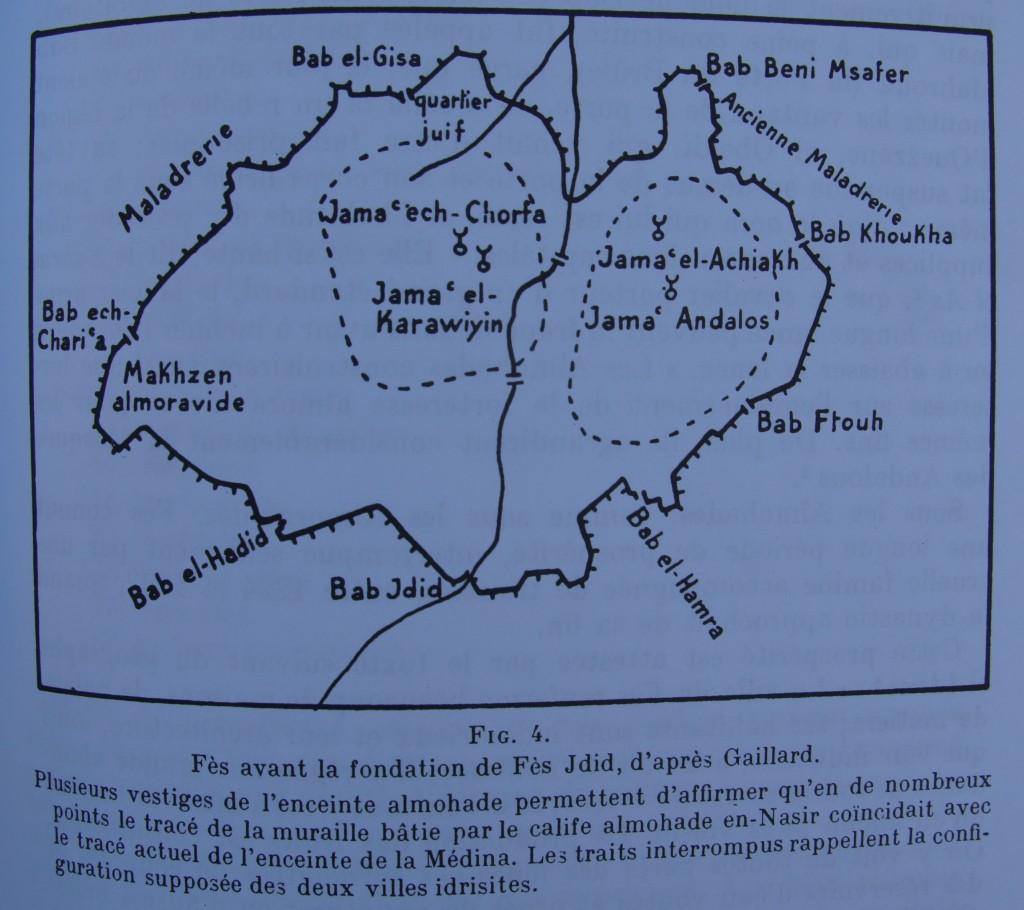

Both groups (from Kairouan and from Cordoba) were displaced by conflicts within the Islamic empire, but they arrived in Fez with different cultural assumptions and expectations–and they seem to have maintained those distinct cultures as they maintained the walls of their separate villages (and mosques). Jama’a means gathering–in the context of the map above, it means the gathering of the faithful in a congregational mosque. Fatima el Fihri, daughter of a wealthy businessman from Kairouan, founded the Qarawiyine mosque in 859, just 35 years after the refugees arrived in the city. The medersa, or Islamic school associated with the mosque, is the oldest continuously functioning university in the world.

Photo by Hans Munk Hansen, in the David Collection, Copenhagen

Now if all that that wasn’t complicated enough, let’s add in another factor: shortly before the founding of Fez, another important Moroccan city was founded: Sijilmassa, gateway to the Sahara and to the lucrative gold trade with Western Africa. Fez and Sijilmassa were cities in competition with one another, but their fortunes were also closely linked by the trade routes that fed them both. (Sijilmassa is in the midst of the palm tree symbols below Fez.)

Fez enjoyed the status of (contested) imperial capital for a couple of hundred years before being displaced by Marrakesh, a capital founded by the new dynasty of rulers, the Almoravids. The next dynasty, the Almohads, founded Rabat in their turn. But Fez continued to grow and thrive, becoming by some accounts the largest city in the world at that period (1170-1180). And the next dynasty, the Merenids, turned back to Fez, creating a new capital in Fez Jdid, effectively building a new city beside the old medina of Fes elBali, just as the French would do many centuries later with the “villes nouvelles” of the protectorate era.

Despite its imperial vicissitudes, then, Fez grew and prospered throughout the medieval period, thriving on the trade routes that brought wealth and culture to its many doors. And the Alouite dynasty, reigning from the seventeenth century to the present day, made a practice of ruling as a kind of circuit court, visiting each imperial city (and potentially troublesome region) of the kingdom in turn. This practice meant that each of the major cities shared in the royal attention and resources. As a result, the modern city of Fez–like the other imperial cities, only more so– is a kind of living palimpsest, with layers of history piling one on top of another.