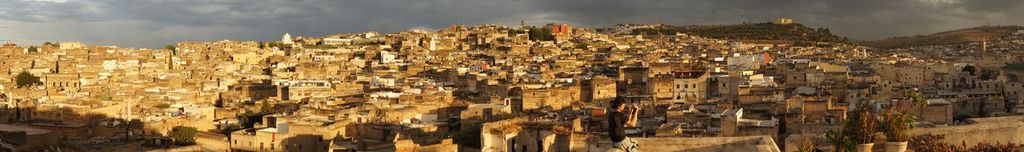

The city of Fez is shrouded in a mist of nostalgia. [Note: Fez in Arabic is spelled Fas; the adjective for things associated with the city is Fassi.]

[Note: Fez in Arabic is spelled Fas; the adjective for things associated with the city is Fassi.]

Everyone who writes or speaks of it—and there are many people who love this city deeply—seem also to speak of its present state as a dim reflection of its past glory; often, they describe the city as perched on the brink of destruction.

The local bakeries are closing; the public fountains are drying up. The buildings themselves are on the edge of collapse, some or many of them, depending on whom you talk to.

I find myself totally caught up in this sense of imminent ruin, only to remember that Edith Wharton was already marking the city’s demise in the 1920s, and Paul Bowles foretold its end in the 1950s. [In what follows, I don’t mean to downplay the real threats of overcrowding and limited resources–I’m just struck by the persistent perception of imminent demise.]

Wharton, an enthusiastic supporter of empire, is hard to read today: her prose is at times wonderfully detailed and energetic, but it is almost always marked by a willful prejudice, a pre-judging of what she sees. Her “first vision” of Fez is introduced by the ideological (and clearly false) claim that “Nothing endures in Islam except what human inertia has left standing and its own solidity has preserved from the elements. Or rather, nothing remains intact, and nothing wholly perishes, but the architecture, like all else, lingers on half-ruined and half-unchanged.” I want to distance my view from Wharton’s, but she too is focused on Fez’s liminality.

“There it lies, outspread in golden light, roofs, terraces, and towers sliding over the plain’s edge in a rush dammed here and there by barriers of cypress and ilex, but growing more precipitous as the ravine of the Fez narrows downward with the fall of the river. it is as though some powerful enchanter, after decreeing that the city should be hurled into the depths, had been moved by its beauty, and with a wave of his wand held it suspended above destruction.” Note how “dammed” evokes the idea of damnation just before Wharton changes direction from religion toward a narrative that might have come from the Thousand and One Nights.

Paul Bowles had his own predispositions. He wrote in his preface to The Spider’s House, “I wanted to write a novel using as backdrop the traditional daily life of Fez, because it was a medieval city functioning in the twentieth century.” The struggle for independence intervened, however: “I soon saw that I was going to have to write, not about the traditional pattern of life in Fez, but about its dissolution.”

But has traditional life really dissolved? Or has it just morphed to include high top sneakers and modern shoes along with seasonal mandarins and beans?

But has traditional life really dissolved? Or has it just morphed to include high top sneakers and modern shoes along with seasonal mandarins and beans?

Sure, there’s an uncanniness here: a medieval city in the modern world,

minaret with satellite dishes

an acclaimed World Heritage Site that survives partly on its own terms, but largely as a simulacrum of itself, offering up its performance of authenticity to the tourists whose influx of money keeps the life support functioning. I don’t mean this critically: I’m fascinated by the liminal status of Fes, and even more fascinated by the length of time that liminality has lingered.

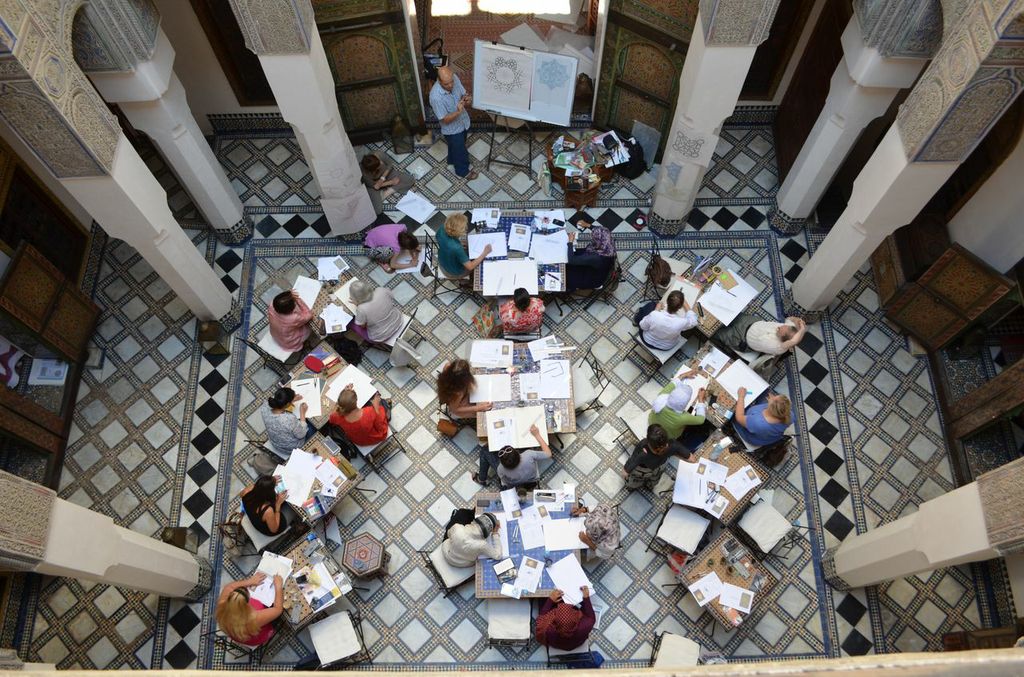

I hope you will linger in Fez with me for the next week or so. I have come down the mountain from Ifrane to Fez to take a study tour of “The Art of Islamic Pattern” led by two British artists and teachers: Richard Henry and Adam Williamson.

The course includes teaching sessions on the geometrical and biomorphic patterns of local Islamic art, along with tours of the medina—tours focused on architecture and traditional arts. Disclaimer: as a result, my image of Fes is shaped by a number of English-speaking interpreters, guides, teachers (and of course books in both French and English). So here’s what’s coming up: a quick primer on the history of Fez in relation to the rest of Morocco and the Islamic empire; a glance at Fez as a palimpsest, full of historical layers and overwriting; an overview of domestic architecture; a glance at some of the logic underlying geometric pattern in Fassi zellij or tile mosaics; a still briefer glance at some principles of biomorphism in Fassi plaster and wood carving; and a trip through the artisanal centers of Fez, divided into four separate posts. Lots of photos and not too many words, I promise!