It feels as if we’ve only just returned from the Tafilalt, but John Shoup is taking a group of students to do field exercises in Meknes, and he’s agreed to let us tag along again: he’ll show us some of the monuments in Meknes while the students are busy with their exercises.

It’s a drizzly day, and the hour-long bus ride seems a little subdued. We pass fields with these odd-looking structures.

When we first arrived, I asked someone about the long strips of piled stone: were these stone farms, I wondered? Did construction companies come and gather a strip of stones at a time for building purposes? No, no! It’s busla! (Onions.) The area between Ifrane and Meknes is a big onion-growing area, and these strips are a storage technology. The stones keep the onions off the ground and away from (at least some) moisture. Within the curve of the stone, you place a layer of straw, then a pile of onions, then more straw, and finally plastic to keep the rain off. Insh’allah, the onions will keep through the winter, to furnish the souqs and the hungry people around Morocco.

The students are being sent out in groups of 3-5 people (with at least one good Arabic speaker in the group) to try to identify which parts of Meknes are successful neighborhoods. At lunch, one group shows us their photos: a friendly woman invited them into her house (hugs all around) and introduced them to some of her neighbors. The students are thrilled with their experience. This is one of the reasons John likes Meknes: the town is both smaller and friendlier than Fez, and people welcome his students and their endeavors.

The entry into Meknes does not give that impression, however: Moulay Ismail (1672–1727), who made Meknes his capital city in order to snub the uppity Fassis, invested heavily in stone as a demonstration of state power. Driving into the center of the city, we took the path diplomats would have followed, along two kilometers of a walled corridor that would have been lined with thousands of soldiers. Passing through a tunnel, we arrive at the mashwar or the fore-court of Moulay Ismail’s (second) Dar el Makhzen palace, where those diplomats would have been received.

The courtyard may seem large, but the “Pavilion of Diplomats” in the upper left corner is small enough to administer a snub: you’re not worth my full attention. In fact, John tells us that Lalla Aouda, wife to Moulay Ismail, was an unusually active member of her husband’s government, and often met visiting dignitaries in her husband’s place. In the macho culture of early modern Europe and Morocco, that too might have seemed a snub to foreign diplomats.

The small structures emerging from the courtyard provide ventilation for the vast storage chambers underneath. These were used to store grain and other food. Two years ago, John was present when workmen were installing chains to go along with the more intriguing story that these chambers were a dungeon. “No truth in that story,” notes John. “The chains are only two years old.”

We cross Lalla Aouda square, with the minaret of the Lalla Aouda mosque in the background (photo Eric Ross).

This is the forecourt of what was once Dar Lakbira (the Big House), Moulay Ismail’s first palace–of the three he built. As Eric notes on his blog,

“Over the course of his reign [Moulay Ismail] built three successive palaces, and surrounded these with multiple ramparts that enclosed an area more than ten times larger than the pre-existing city of Meknes, still largely confined within the Almohad walls. The palace-city included neighborhoods for civil servants and the army (largely slaves), vast storage facilities, stables, reservoirs, flocks, fields and gardens. So large was Moulay Ismail’s imperial city that within its walls, today, we find: the current Royal Palace (the second to be built by Moulay Ismail), dense urban neighborhoods (some old, others new), a military academy, a horticultural institute, a track for horse races and other outdoor sports facilities, a golf course, a university campus, as well as monuments open to the public.”

The Bab Mansour (also known as the Victorious Gate) connects the old medina to the palace-city of Moulay Ismail. The gate is named for its architect, El-Mansour, who played on Almohad design patterns and used marble columns from the Roman ruins of Volubilis (Oualilia or Walïlï). Moulay Ismail supposedly inspected the gate upon its completion and asked El-Mansour if he could have done better. El-Mansour felt obliged to answer yes–and in frustration, Moulay Ismail chopped off his head. The only problem with this story is that the gate was apparently completed five years after Moulay Ismail’s death. In any case, the glory of its architecture is addressed not to foreigners entering the city, but to the inhabitants of the city itself, when they turn toward their king. The gate is now a gallery which one enters through a side door, creating an uncanny tension between grandeur and indirection.

John leads us first to the Bou Inania medersa. This, like its larger namesake in Fez, was built under the Marinid dynasty (built 1331-1351). I’m struck by the way the lower level of the building, lined with zellij and cedar screens, gives the effect of being underwater, or a watery reflection, as if the main level of the building started half a story above ground.

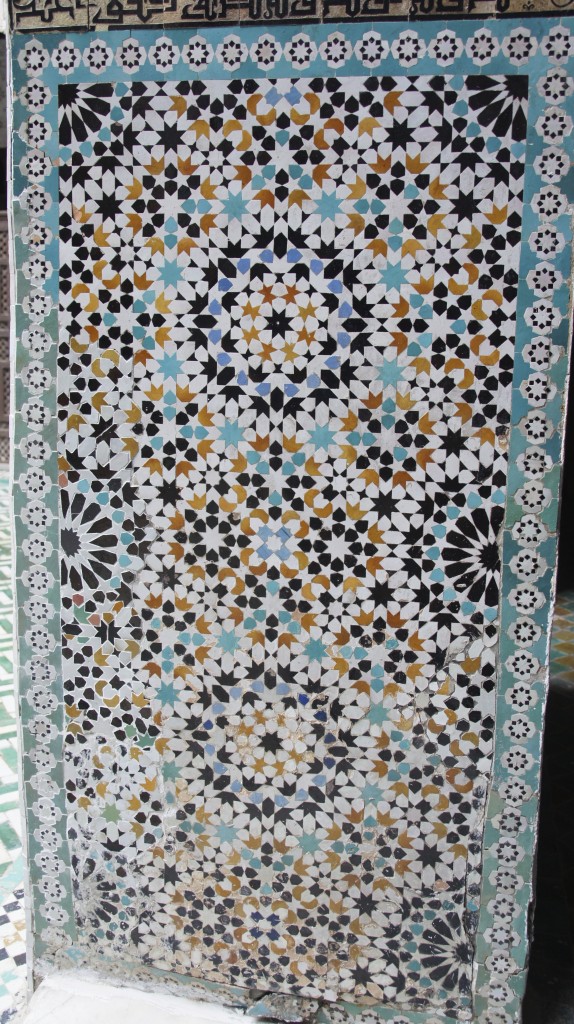

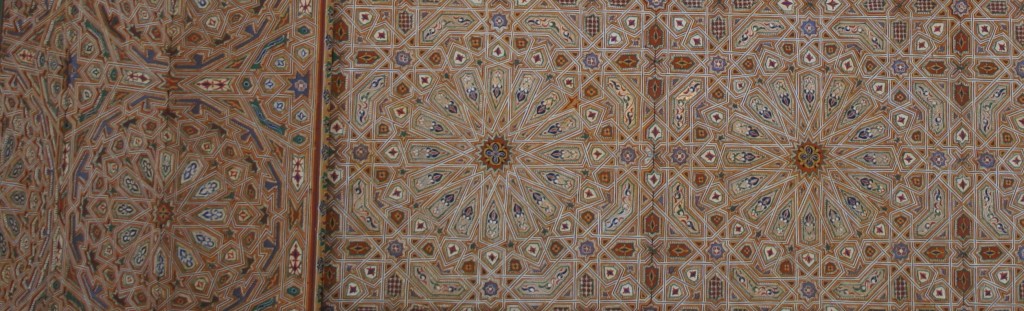

The zellij here is truly remarkable, with all the sophisticated complexity of the Andalusian style:

John tells us to find the center of the pattern (here, the black eight-pointed star) and count the number of layers of decoration radiating out from that center. I count nine layers out to the light blue stars, for what it’s worth. But notice too the excruciatingly small black and white tiled circles around the outside of the pattern. I’m very taken with the multitude of shapes and play of colors here.

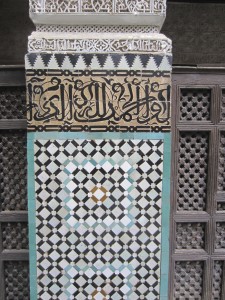

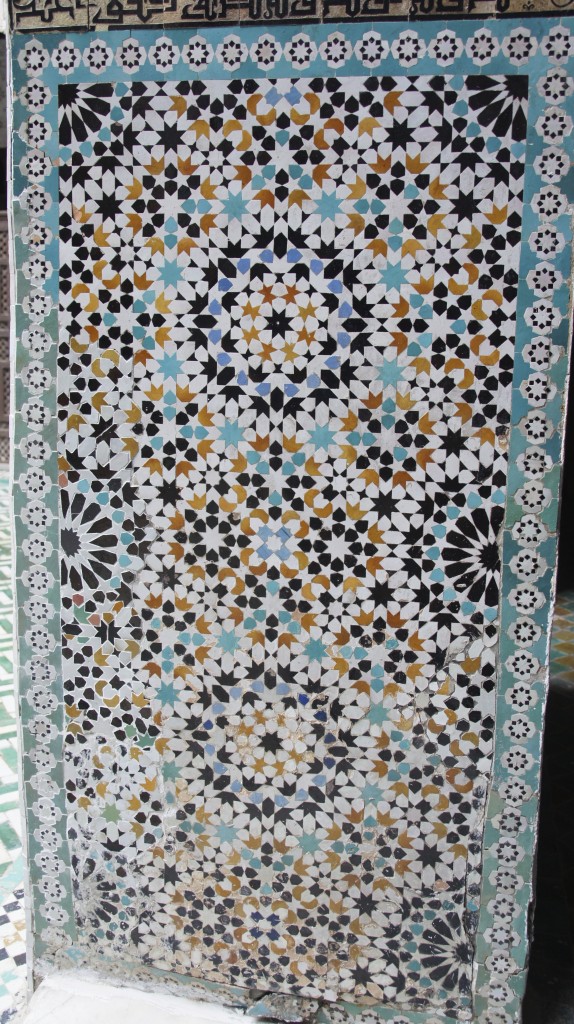

In other places, the zellij is quieter, more subtle, in a way that seems sophisticated to me:

Shadow patterns within patterns.

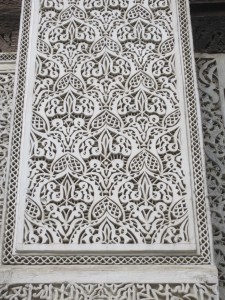

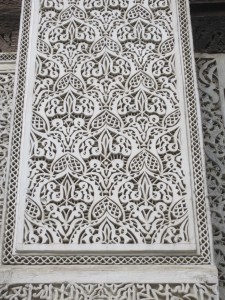

The plaster work also strikes me as quite phenomenal. Is it easier to follow, or am I getting better at seeing the grid?

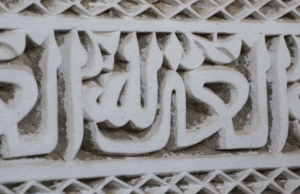

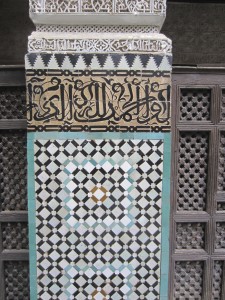

I like the integration of calligraphy and biomorphism here:

And the stark geometry of the medallion, surrounded by biomorphic design here:

And what about rosettes intersecting with other rosettes here?

John tells us a little about the work of the medersas, an intermediate level of Islamic schooling. Students would have begun their educations in kuttabs or msids, schools often attached to a mosque or a zawiya. Such schools would teach the beginning elements of Arabic speaking and writing, along with memorization of early (shorter) surahs. More talented and motivated students would arrive at medersas, and their goal would be mastery of the Qur’an in its entirety. Students would also study astrology, astronomy, and law. Astrology was linked to the human body and its health; astronomy was important for Islamic practices, ranging from certainty about when to perform the five daily prayers to advance warning about the timing of holy days.

In studying law, the student’s job was to memorize not only the primary texts of the law or sharia, but also all subsequent discussions of the primary text within the tradition. This education would conclude with an oral exam in which each student would be presented with a hypothetical legal case and asked to solve it by quoting from memory (word for word) both the main source of law in this area plus all subsequent texts on the subject, along with an account of how the student would apply these texts. Students who passed this test would be awarded an Ijazah and given a robe and a turban–the origin of graduation robes and mortarboards in the West, where educational systems lagged behind this level of medieval Islamic development.

At Independence, 30% of the Moroccan population was educated (could read and write) and almost 100% of those educated people came from these medersas. The medersas were closed in the 1960s, to be replaced by public schools. The fact that the Bou Inania no longer functions as a school or a religious center means that we can climb the stairs to look at the student dormitories.

This room might have housed two older boys: windows became available as you moved up in the hierarchy. Larger rooms would have housed four boys. There would never have been much space to spare. Yet you would have been fed, and housed, given one new set of clothing each year, plus enough freedom from other tasks in order to dedicate yourself to mastering the Qur’an and its applications to law, life, and theology. Medersas and their students were funded by wealthy merchants or craft guilds for the honor they brought to the city. Still, everyone knew boys would be boys: the doors to these rooms lock from the outside, and there were common accounts of students slipping away from the medersa over the rooftops and trying to sneak back in again late at night.

We climb up to the roof ourselves to look at the renovated minaret. In 2010, the minaret of the nearby Bab Berdieyinne Mosque collapsed during Friday prayers, killing 41 people and injuring many others. The king ordered that minaret rebuilt to historical specifications and other minarets inspected and renovated to prevent further damages.

James likes the beldi (traditional) tile of the rooftop.

We ask John the meaning of the three golden balls mounted on the top of many minarets in Morocco. He tells us the traditional story: the chief wife of a sultan in Marrakesh is supposed to have broken her Ramadan fast with 3 pomegranate seeds; in remorse, she had all her gold jewelry melted down and made into three “seeds” to be mounted on the Koutoubia minaret in Marrakesh, to the glory of Allah.

Time to leave and wander the medina for a while.

Look familiar? Think of the Attarine in Fez…

.

.

The photo is out of date: the minaret has since collapsed. Of the satellite image, Eric notes “The actual shrine (mosque, mausolea, cemetery) in the north part of complex was destroyed by a flood in the late 1960s and is now completely ruined. Members of the Sufi order meet in the Guest House, next to the Shaykh’s house, in the complex’s eastern village. Half of this village too is ruined. The village at the west of the complex contains the shrine of Sidi al-’Arbi al-Ghâzî.”

The photo is out of date: the minaret has since collapsed. Of the satellite image, Eric notes “The actual shrine (mosque, mausolea, cemetery) in the north part of complex was destroyed by a flood in the late 1960s and is now completely ruined. Members of the Sufi order meet in the Guest House, next to the Shaykh’s house, in the complex’s eastern village. Half of this village too is ruined. The village at the west of the complex contains the shrine of Sidi al-’Arbi al-Ghâzî.”

There you are, driving through the desert, and you see a bunch of enormous anthills. Really? Ant-hills? Maybe mole hills? How big are those moles? The size of camels?

There you are, driving through the desert, and you see a bunch of enormous anthills. Really? Ant-hills? Maybe mole hills? How big are those moles? The size of camels?

What’s visible on the surface are merely the waste piles: the heaps of sand and scree dug out of the water channel and removed to the surface of the earth.

What’s visible on the surface are merely the waste piles: the heaps of sand and scree dug out of the water channel and removed to the surface of the earth.

Area of heavy resistance to the French

Area of heavy resistance to the French