On the second day of our trip to the Tafilalt, John and Eric took us to visit a qsar that now houses a museum: Qsar al-Fidha.

First, we looked at some qsur (plural of qsar) from the outside, and talked about pisé or rammed earth construction.

As we saw in the construction of the Fez medina, pisé or rammed earth architecture is both sustainable and locally appropriate. The thermal mass of the thick walls offers insulation, keeping housing cool in summer and warm in winter. Typically, construction uses subsoils low in clay, saving topsoils for agricultural use. The mud can be shaped into bricks which are sun-dried; these are then stacked in a temporary frame and connected using a mud slurry. Alternately, damp soil can be poured into the frame and directly tamped down using ramming poles, working up 4-10 inches at a time until the top of the frame is reached.

According to Wikipedia, rammed earth holds humidity “between 40% and 60%, the ideal range for asthma sufferers and for the storage of such susceptible items as books.” For an academic with an asthmatic child, this is of no small interest! The width of rammed earth construction also offers significant sound-proofing, helpful when an entire village is living cheek-by-jowl.

The downside of pisé construction is the ongoing labor of its maintenance. A new earth-based rendering needs to be applied almost every year in order to keep the walls from dissolving in the winter rains. And the communal nature of the qsur means that if your neighbor lets her house disintegrate, your house is much more vulnerable to decay. Here, external ramparts work to support a wall whose decay threatens its neighbor.

The process of decay also makes visible the rammed earth bricks underlying the connective slurry.

The process of decay also makes visible the rammed earth bricks underlying the connective slurry.

Another example of earthen bricks in the process of decay; water pipes working direct water far from the rammed-earth walls.

(John also mentioned a 20th century Egyptian architect, Hassan Fathy, who works with rammed earth. Unfortunately, Fathy’s carefully designed rammed-earth village has suffered from salt-stone foundations; if you’re interested, the village is featured in this video: https://vimeo.com/15514401. Rammed earth is becoming a hot topic on sustainable building sites: check it out.)

On to Qsar al-Fidha! Eric describes the “onion” layering of this particular qsar: a large outer courtyard, surrounded by walls; a smaller inner-walled compound, with additional buildings around the edges; a central compound which was occupied by the governor of the local province, “always a member of the royal family.”

The first courtyard or mashwar is big enough to allow the drilling and display of military force, though at the moment, it mostly makes for a long walk for women and girls collecting water.

In the photo below, our host Abdullah, the head of the museum, proudly descended from the upper slaves of the royal family, crosses the mashwar to prepare for our visit. Certainly, the size of the space has a psychological effect on a lonely visitor.

When you pass through the gate pictured above, you find yourself facing a wall: this was an obvious architectural defense strategy, breaking the momentum of any possible enemy charge:

A second “elbow” turn in the structure of the qsar served as a guardpost, where the guardian of the village could keep an eye on everyone coming in and out (and what they were carrying). In this particular qsar–the qaidate, or the local center of government–the guard post would also have been the place where taxes were delivered and counted. Taxes were paid in kind, so people would have brought bushels of wheat, quantities of dates, heads of sheep and so on. This would also have been the courthouse, where unresolved conflicts across the oasis would have been brought to be decided by the governor, or more likely his deputy. The finer stucco finish of this gate area speaks to its grander purposes (unfortunately, the photo doesn’t give much sense of the space included in the L-turning).

Soon after the guard post, the corridor/street gives access to the mosque and the well. Two things you could not refuse a traveler: water and a place to pray. (But you could position those resources close to the guard post so that you could keep an eye on those dubious strangers.)

The well only provides water for washing now–the water quality is too low for drinking or livestock or irrigation–hence the long walk out to the more modern water fountain.

The next layer of the onion brings us to the governor’s palace. Here, we see classic white-and-blue plasterwork designed to rest the eyes from the glare of the sun as you enter a darker space.

Before we get to that restful vision, however, we pause once again in the antechamber to hear John’s account of the qaidate under the French and earlier.

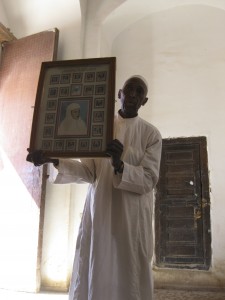

Our host, Abdullah, is proud of his lineage, drawn from high-level palace slaves. Here he holds pictures of the Alawite dynasty his family has served through the generations. As John explains it, Abdullah’s father would have been given as a slave to the son of the governor when he was a boy. The two boys would have grown up together, as intimates, closer than brothers, since the royal boy’s brothers would be competing with him for power. Once grown, the governor’s slave would be the second most powerful man in the region, offering a separate channel of access to the governor. People would approach the governor’s advisor (rather than the unapproachable governor) and pay him to put their case to the governor. The advisor-slave would maintain his power by being absolutely honest with the governor, so he would have to choose the cases he accepted with care.

Audiences held in the antechamber probably featured the governor sitting in front of a curtain, a curtain that could serve many purposes: decoration and demonstration of power, but also a hiding place for the governor’s advisor/slave. The governor in thinking over an issue raised by an audience could lean back slightly to hear from behind the curtain the views of his slave advisor on the matter or the people at hand. (Yes, yes, the wizard of Oz and the man behind the curtain definitely comes to mind here.)

But these kinds of governing structures also had a role to play under colonialism, also known as the French Protectorate.

The Tafilalt was one of the last parts of Morocco to fall to the French. The center of this region fell in 1930; the outskirts, down to Zagora, held out until 1933. The battle around Jebel Sahro cost the French more officers per capita than were killed in World War I. (Local people targeted the easily-recognizable officers, having realized that the rest of the soldiers didn’t know what to do if the officers were killed.) Force majeure concluded the struggle: the French brought over their long-range artillery from French-held Algeria and bombarded the town until concessions were finally made.

Area of heavy resistance to the French

Area of heavy resistance to the French

Victory was relative. Our host remembers his father answering the phone, setting the receiver down, and walking away. An hour later, he might return, pick up the receiver and say, “Oh! you’re still there! I forgot about you!” The message? “The qaid rules here, not the French. You will have access to the qaid when I feel like granting you that access, not before.”

So the French would have to get in a jeep and drive from Erfoud to this qsar in Rissani, just above Merzouga–only to find that they were kept waiting at the gate until someone could be bothered to let them in. Same basic message. This kind of passive resistance persisted for some 20 years. Only in the 1950s did the French decide to move the administrative center to Rissani, shifting the caid’s office to the same building, in order to acquire ease of access. Until independence in 1957.