Early in the morning of Eid el Adha, I am listening to the sheep in the neighbor’s garden, waiting for the slaughter. For days, we have been watching the sheep go by, strapped onto the top of busses, lashed onto the backs of bicycles, driven in herds to the edges of towns.

I find myself braced, physically tense, as I listen to the children squealing, the noise increasing in pitch and intensity. Still the sheep bleats: I am waiting for it to bleat its last.

Ignorant as I am, the first details I learned of Eid el Adha came in discussion of Eid el f’tur at the end of Ramadan. Eid el f’tur (breaking the fast at the end of Ramadan) is also known as the “little Eid” (eid el sghir) versus the “big Eid” (eid el kbir) which is Eid el Adha. “So what happens during the Eid el Adha?” I asked Youssef. “What makes it the big celebration?”

“It’s the festival of the sheep,” he told me, which left me even more befuddled. What’s so special about sheep? This is a religion opposed to idols, right? Surely they’re not worshipping sheep.

“What happens, exactly?” I asked Youssef, and his face lit up. “My family all gathers. My father has bought a sheep. My brothers and I hold it by the legs, with the head up (miming a tussle), and my father cuts its throat. Then we hang it up and we pull the skin down and off.” Youssef’s Darija was punctuated by vivid explanatory gestures. I held up my hand to stop him: this was perhaps more than I wanted to know. But after Youssef left that day, I looked online and found multiple photos and descriptions of travelers encountering piles of sheep corpses on street corners. It occurred to me then that Spain might be an appealing destination for my vegetarian family over the Eid holiday.

But Eid has come and here we are. It’s almost 10 a.m. The children are still squealing in the garden behind our house. At the front, on our left, adult voices build, peak, recede. I hear the scraping of a shovel on the ground, the click of a bucket handle as the bucket is picked up and set down. I hear running water. I can’t seem to turn off my imagination’s visual accompaniment to this particular soundtrack. Inside our house, Jeremy is listening to the story of Mozart’s musical childhood. Outside, there are more sweeping and scraping and popping sounds. Are they chopping the sheep—separating the joints?

Another man stops by next door. “La bas?” (“What’s up?”) There is a guttural satisfaction to the exchange: I’m not sure of the exact words that follow, but I’d swear they translate to something like, “Now that’s the way to kill a sheep.”

James and I go out on the balcony and look over into the courtyard next door, where a sheep carcass hangs by its back legs, all pink and white.

I rethink “popping” as a description for the noises I heard: it must have been the sound of the skin being peeled off the body of the sheep, inch by little inch. Ripping, snapping, perhaps. On the wall across the road, the skin hangs, like a pair of footy pajamas turned inside out. It waits, as a gift, for whoever may need it.

Meanwhile, the sheep’s head is roasting on a fire the neighbors have built in a metal wheelbarrow: it looks both unreal and a little too lifelike.

James goes over to greet the neighbors: they welcome him in, past the hanging carcass. They encourage him to take photos; they force-feed him sweet tea and cookies. They urge him to bring me over as well, but he demurs on my behalf, pleading a combination of illness and vegetarianism. I wave from the balcony, feeling like an old-style Moroccan housewife, happy to keep my Eid a vicarious experience.

11 a.m. Around the neighborhood, smoke is rising from a dozen courtyards or more. The smoke and smell of roasting flesh drift into the house and I close the doors and windows. The noise of bleating sheep has diminished but not disappeared. Zoë swears she hears the sheep screaming; my hearing is not so finely discriminated, but the bleating is sometimes more frantic in quality, and sometimes abruptly interrupted.

There are thudding sounds from next door and I wonder again if they’re quartering the sheep. The family eats one quarter, gives a quarter to the poor, preserves a quarter, and gives a quarter to a second cousin or similarly distant relative. But no: still the pink and white carcass hangs, complete. James reports that the noise is the removal of the ram’s horns, before the head is returned to the roasting wheelbarrow. Eventually, they’ll crack open the skull and eat the roasted brain: a delicacy.

Noon: James takes Jeremy off to visit our friend Said, at Said’s father’s house, carrying a cake we bought to contribute to their festivities. On the way, James and Jem watch a sheep being skinned; near the entrance to the house, they pick their way through pools of watery blood. Said apologizes for what he names the unsanitary conditions—James responds honestly that he’s very taken with everyone’s openness and communal celebration.

Still the sheep in back of our house continues to bleat. I’m starting to feel grumpy with that slow-moving family. For the sheep’s sake, get on with it, people! A small child’s squalling blends with the more distant bleats. Online, the Huffington Post presents photos of Eid el Adha from around the Muslim world in 2012. Each photo includes the explanation that the holiday celebrates Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son Isma’al. How did I manage to ignore this for so many years?

I prefer the Muslim version of the story, really: Isma’al acceding to the sacrifice, unlike poor innocent, ignorant Isaac. The Muslim Ibrahim, like his God, asks more than a father should dream of asking—but the Judeo-Christian Abraham seems to me to betray both the duty of a father to protect his offspring and the truthful relationship of a father with his son.

In both cases, the readiness is all: Allah and Yahweh both permit the substitution of a ram for a son, right at the brink of destruction. In the Muslim version of the story, Ibrahim is rewarded for his obedience with a second son, Isaac. What does Isma’al receive? A lifetime of sibling rivalry? Does it take a ritual sacrifice of a first child in order to have a second?

Finally, all the sheep—even the one behind our house—are silent. James returns home, impressed at the number of people so very competent at managing the slaughter that that undergirds carnivorous consumption. This is more honest, he insists, than a lifestyle in which killing is rampant but almost totally denied.

We bake a chocolate cake and make lentil soup for a gathering of Americans abroad. “The Al Akhawayn Christmas party!” one of our guests quips.

The day after our party, a man comes down the street on a bike with a cart hooked to the back to collect the hanging sheep skins.

“Why don’t they shear the sheep first?” asks Zoë. “It seems so wasteful. All that wool gone to waste.”

I gesture at the stuffed wool cushions that make up the banquettes on which we sit. “They don’t go to waste.”

Zoë makes a face. “I wish you hadn’t told me that.”

The photo is out of date: the minaret has since collapsed. Of the satellite image, Eric notes “The actual shrine (mosque, mausolea, cemetery) in the north part of complex was destroyed by a flood in the late 1960s and is now completely ruined. Members of the Sufi order meet in the Guest House, next to the Shaykh’s house, in the complex’s eastern village. Half of this village too is ruined. The village at the west of the complex contains the shrine of Sidi al-’Arbi al-Ghâzî.”

The photo is out of date: the minaret has since collapsed. Of the satellite image, Eric notes “The actual shrine (mosque, mausolea, cemetery) in the north part of complex was destroyed by a flood in the late 1960s and is now completely ruined. Members of the Sufi order meet in the Guest House, next to the Shaykh’s house, in the complex’s eastern village. Half of this village too is ruined. The village at the west of the complex contains the shrine of Sidi al-’Arbi al-Ghâzî.”

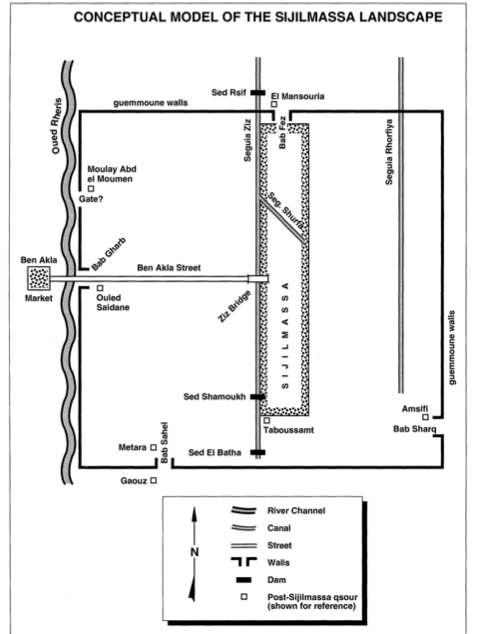

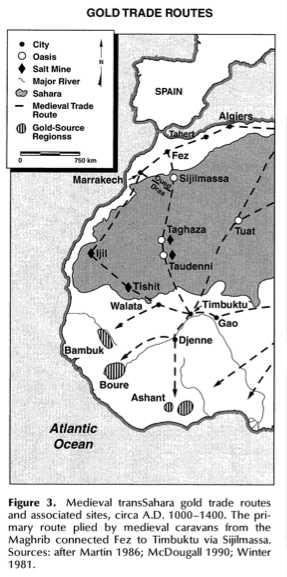

What remains of Sijilmassa today are actually the ruins of a mosque built in the 1600s and 1700s by the Alawite dynasty. These are atmospheric if somewhat misleading: I spent ages imagining (incorrectly) thousands of camels parading through these walls.

What remains of Sijilmassa today are actually the ruins of a mosque built in the 1600s and 1700s by the Alawite dynasty. These are atmospheric if somewhat misleading: I spent ages imagining (incorrectly) thousands of camels parading through these walls.

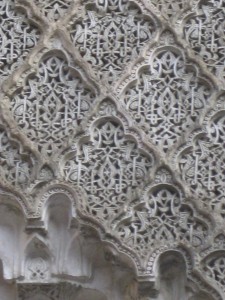

(Image from Lightfoot & Miller, 1996)

(Image from Lightfoot & Miller, 1996)

Sama straightening out one of my many confusions…

Sama straightening out one of my many confusions…

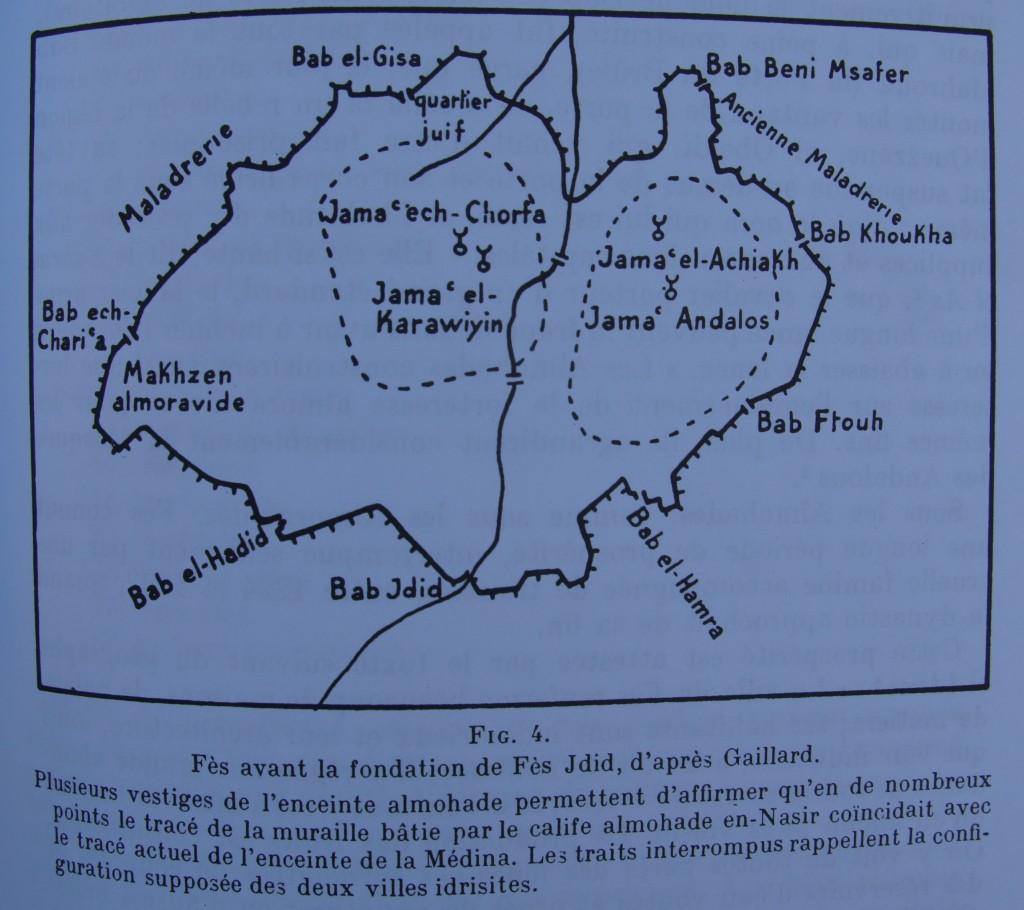

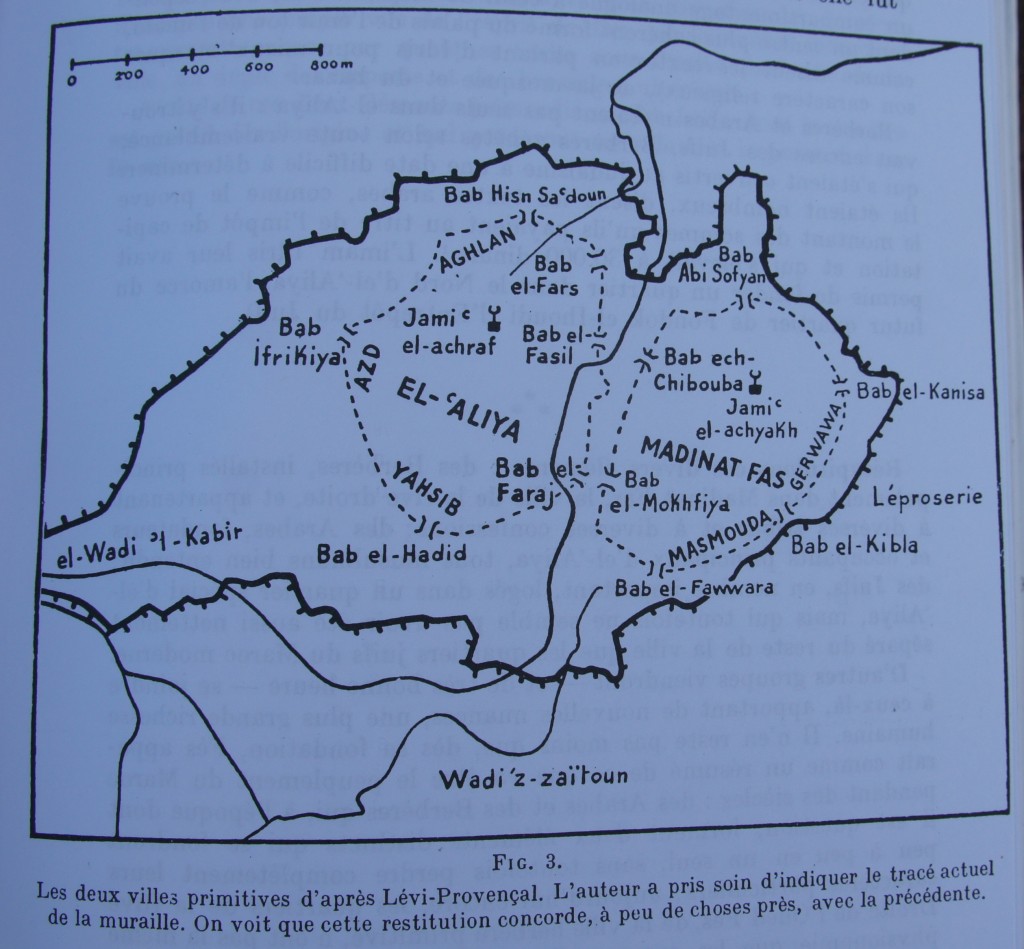

Notice the important rivers (wadis or oueds) running between and around the two towns

Notice the important rivers (wadis or oueds) running between and around the two towns