Before the Tafilalt became known as the Tafilalt in something like its current configuration, the oasis was the ground of a glorious medieval city: Sijilmassa.

Sijilmassa was founded in 757 by people following the Kharijite vision of Islam: a vision of radical egalitarianism, in which any devout person could become the leader of the community, and all Kharijites were called to fight against unjust leaders. Yet by 956, Sijilmassa was the epicenter of the Trans-Saharan trade: a trade based on the exchange of salt for gold and slaves. Surely this central irony ranks right up there with the life of American founding father Thomas Jefferson .

The roots of Sijilmassa–and thus a large portion of Moroccan history–lie in both the success of and the fractures within the early Islamic empire. Here’s the shortish version of the story: in the ten years after Mohammed moved to Medina, the entire Arabian peninsula became part of the early Islamic empire (622-32; brown on the map below); in the subsequent 30 years, under the Caliphate (the early successors to Mohammed), it spread both east and west (632-661; orange territory); under the Ummayid dynasty, it expanded through Morocco, Spain and Portugal (661-750; tan on the map). That is an impressively rapid imperial expansion:

(image from Wikipedia)

(image from Wikipedia)

As you may remember, the fourth caliph (successor) was Ali, Mohammed’s son-in-law, and his rule was marked by a struggle over power. Those backing Ali and refusing to recognize the first three caliphs became known as Shi’a (the party of Ali); those backing the other three caliphs became the majority Sunni power.

The less-known part of this story takes place on a battlefield during Ali’s rule, when the opposing army tied copies of the Qur’an to their lances. A significant portion of Ali’s troops (traditionally 12,000) refused to fight on these terms; negotiations ensued, in which Ali’s negotiator somehow agreed that Ali should abandon his claim to the caliphate altogether (!). The dissenting troops withdrew in disgust from the battlefield and from Ali’s army, rejecting both the negotiations and the negotiators: they came to be known as kharijites (those who left).

Kharijites believed that any pious Muslim could be a leader of the Muslim community (membership in Mohammed’s tribe or family was not required); kharijites were also quick to name as unbelievers any leaders who acted against the principles of the Qur’an–such fallen leaders should be deposed or even killed. Kharijites insisted more emphatically than other Muslims on the radical egalitarianism enshrined in the Qur’an; the Haruriyya, an early kharijite group, even believed women as well as men could serve as imams. (It was also a Haruriyya who assassinated Ali, five years into his reign.)

By the 720s, small groups of Kharijite refugees, persecuted by the Abbasid caliphate of Baghdad and Kairouan, had arrived in the western Atlas mountains. Imazighen (Berber) inhabitants of the area were themselves in search of religious legitimation—a way to practice Islam without acceding to the Arab elites controlling more established urban centers of the Maghreb. Kharijite insistence on egalitarianism, an Islam open to non-Arabs, was popular in this context.

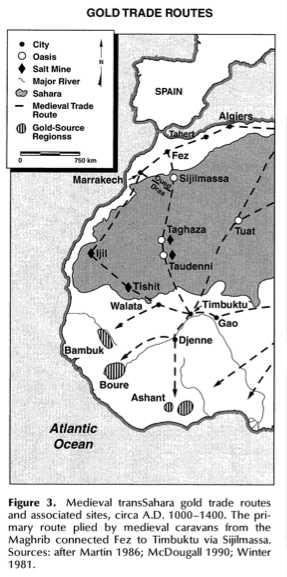

By 740, Kharijite agitators were associated with a massive “Berber revolt” across the Maghreb; in 757, Kharijite-inspired Zenata Berbers founded the city of Sijilmassa by the banks of the river Ziz. Benefiting from the support provided by the oasis there, Sijilmassa was also perfectly placed to profit from the West African gold trade: by 956, some sources said that Sijilmassa minted all the gold coming north from the Sudan.

(Image from Lightfoot & Miller, 1996)

(Image from Lightfoot & Miller, 1996)

But of course the gold trade was never only a trade in gold and salt: according to some estimates, from the tenth century on, roughly 6000 slaves were sent north each year along the Trans-Saharan trade routes. So how did a city founded on a belief in radical egalitarianism come to be the center of a slave trade persisting for many centuries?