Sijilmassa might have been founded by Kharijites and their supporters, but the rich city, repeatedly conquered by reforming dynasties such as the Almoravids (1055-1146 in Sijilmassa) and the Almohads (1146-1269), soon had the heterodoxy beaten out of it. The Almoravids smashed musical instruments and closed down wine shops throughout the city; Almohads massacred many of the Jews of Sijilmassa. Yet the city as a whole expanded after the Almoravid conquest (1054) and “retained its enlarged importance through the Almohad period” as a result of improved water resources: the redirection of Ziz to the center of the Tafilalt. [Lightfoot & Miller]

So what did Sijilmassa look like, back in the day?

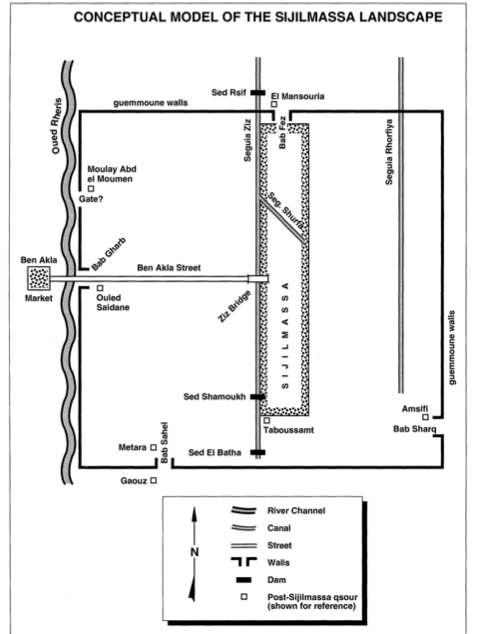

Here’s Lightfoot and Miller’s conceptual map of the city, drawn from oral histories of the area as recorded in the mid-1990s:

A long, thin city, bordered by a canal on one side, surrounded by a walled oasis.

Medieval historian Al-Bakri, drawing on the chronicles of Ibn Hawqal, records that in 814-5, an early ruler of Sijilmassa, Al-Yasa’, built a wall surrounding the town: the wall had twelve gates, eight built out of iron. Under Al-Yasa’, Sijilmassa also acquired a royal palace, an “excellent” mosque, “lofty” mansions, “splendid” buildings, and many gardens. Field and photo reconnaissance confirms that both the city and the oasis were once walled. [Lightfoot and Miller]

The famous traveller Ibn Battuta came to Sijilmassa in 1352-3 on his way to the Mali empire. Comparing Sijilmassa to cities in China, Ibn Battuta described Sijilmassa as including “orchards and fields and their houses in the middle,” making the city as a whole very large. These houses were undoubtedly different from the fortress-villages of the qsour, but this description shows an established pattern that the later qsur may have built on.

Ibn Battuta spent four months in Sijilmassa, preparing for a two-month Saharan caravan crossing. Camels were traditionally fattened for several months in the area around Sijilmassa to prepare them for the arduous journey.

Ibn Battuta also noted that the average trans-Saharan caravan included 1000 camels; large caravans might include as many as 12,000 camels. Miles and miles of camels.

Mindboggling. You wouldn’t want to be at the back of the queue.

According to medieval geographer Leo L’Africain, the city fell in 1393, when the inhabitants rebelled against the Marinid governor (renowned in oral tradition as the “Black Sultan,” as recorded by Lightfoot and Miller), broke down the walls of the city, quarreled among themselves, and distributed themselves amid the qsur (fortified villages) of the oasis. Writing of his two visits between 1510 and 1515, L’Africain praised the ruins of the city:

The city was built in a plain, on the Ziz, and was encircled by a high wall of which one can still see some parts…. Sijilmassa had fine temples and colleges supplied with numerous fountains whose water came from the river. Great wheels took this water from the Ziz and projected it into conduits bringing it into the city.

Mostly, though, L’Africain saw the fate of Sijilmassa as something like an object lesson in the importance of cooperation:

Back when the people were all agreed, they built…walls to stop the incursion of Arab horsemen. While the people were united, with a common will, they remained free. But factions arose, and they demolished these walls and each [group] called upon the Arabs to protect them. So it is that these people have become the subjects and almost the slaves of the Arabs… always fighting each other, doing as much harm as they can, which is to say damaging the irrigation canals which come from the river, [or even cutting] off palm trees at their trunk and steal[ing] from each other, which the Arabs abet.

You could almost say that when, in the early twentieth century, the French and their Moroccan collaborators destroyed irrigation canals and sabotaged water resources, “manufacturing a fifteen-year-long drought, followed by the 1944-5 famine” (Ilahiane), they were following something of a time-honored tradition.

Now, the al-bayud fungus is one of the greatest threats to the palmerie. Kind of a relief–or maybe not, depending on how seriously your palm tree is infected.

What remains of Sijilmassa today are actually the ruins of a mosque built in the 1600s and 1700s by the Alawite dynasty. These are atmospheric if somewhat misleading: I spent ages imagining (incorrectly) thousands of camels parading through these walls.

What remains of Sijilmassa today are actually the ruins of a mosque built in the 1600s and 1700s by the Alawite dynasty. These are atmospheric if somewhat misleading: I spent ages imagining (incorrectly) thousands of camels parading through these walls.

For a Romanticist, of course, it’s also easy to think of Shelley’s “Ozymandias:”

“Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!”

*****Quotes drawn from from Dale Lightfoot and James Miller, “Sijilmassa: The Rise and Fall of a Walled Oasis in Southern Morocco.” Photos from Tafilalt visit with John Shoup and Eric Ross.