This is how Moroccans give directions: “Drive into town, then call me and I’ll tell you where to go from there.” Really? I have to call you from the roadside and then try to listen to “second left, next right, two roundabouts” in French with bad reception while scrabbling for paper and pencil to write it down? You can’t give me a post code ahead of time and let me look it up on Google maps?

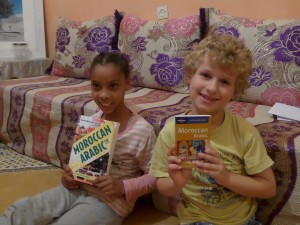

Actually, Google maps are not very satisfactory in Morocco. The site is blanked out over the royal palaces to protect the king’s privacy, for instance, but in addition to that, most city maps include a variety of unlabeled streets along with various streets labeled in Arabic script. Remember that I’m reading at about a first or second grade level. Picture us driving.

James: “What’s the next street we’re looking for?”

Betsy: “Uh, can you pull over and let me sound it out?”

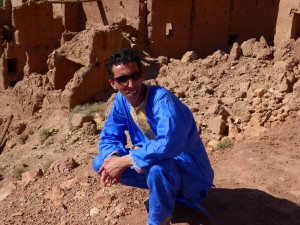

As instructed, we called Aziz once we reached the outskirts of Tinghir. “OK, just drive through town; the last café on the way out of town will be called mflmr. I’ll meet you there.” The name of the café is impossible to catch, even with three repetitions: James thinks it’s Ahmed’s café; I think it’s Mohamed’s. We’re in the midst of rush hour traffic, so it’s hard to drive slowly enough to spot the names of shops or cafés in the gathering dusk. We’re convinced that our plans for the night and the next day have just gone up in smoke. Suddenly, Aziz is standing beside the car, in the middle of traffic, like a ghost appearing out of nowhere. Moroccan magic. (This is the kind of story that annoys me when I read them in books, but still…) Aziz jumps in the car and tells us to turn right and right again and suddenly we’re on a dirt track curving along the bottom of the town. The noise and bustle drop away–we enter a courtyard with a Berber tent, incense rising, and dusk falling.

The auberge seems to be an all-male operation, which may explain a certain degree of grubbiness, but I’m too tired and sick to care. I crawl into bed; Aziz and his brother make me a verbena tisane to try to settle my stomach; James and Jeremy have a couscous from which Zoe abstains, then we all fall asleep.

November 5th: Guy Fawkes day in England: my birthday! As a present, James has organized another tour of the Todgha palmerie (and the children are willing to go along with it). Give Zoe enough sweet mint tea and she can cope with anything.

We bribe Jeremy by telling him Aziz will teach him to weave little camels out of palm fronds, but damn, that’s harder than it looks. (In the palmerie, six-year-olds are already doing this with ease…) Aziz is amused by our struggles with the simple task.

Those of you who know my passion for permaculture will understand my obsession with the palmeries: these are permaculture sites that have been operating abundantly for thousands of years. Our brief earlier tour did nothing to slake my curiosity about the details of how these palmeries are structured and maintained.

We start again at the garden of the Sacred Fish (Poissons sacrées) café and restaurant: a fresh water spring inhabited by salt-water fish. Don’t ask me how this works: that’s why they’re sacred.

They’re hard to see in this picture, but they’re a little scary when swarming (leaping) for bread tossed on the water.

We’re hardly into the palms when Aziz stops for a conversation with a man passing by. The man is his uncle, and they’re discussing the harvesting of a shared family date palm. Aziz noticed that the dates were close to ripe and he told his brother to harvest them. Evidently, there is another branch of the family (cousins to Aziz) with whom this uncle has some issues. “I thought they were harvesting the tree,” said the uncle, “and I was going to give them what for” (a gesture with the hand–coincidentally?–holding a knife) “but then I saw it was your brother, so I left him to it.”

“Are there many family issues about dividing the harvest?” I ask Aziz. “Not really,” he answers. “The best thing is for everyone to be present at the harvest and receive their share. If you can’t be present, then you don’t really have the right to complain.” I’m not quite sure how this statement of principle works out in the context of the family story he just told me, but I don’t press the issue. My family wants to get moving.

“You want to understand dattel farming?” Aziz asks me. “Well, to start with, the farmer has to keep the palm trees pruned properly, or they will not produce. Here, this tree is very messy: many fronds, no dattels.” (I’m not sure why Moroccans call dates dattels–it doesn’t seem to come from French or Arabic or English.)

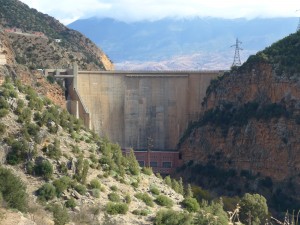

We cross the river which makes this particular palmerie so productive,

looking as we pass at the rock-and-wire bulwarks that people hope will contain the floodwaters when they come, so that the floods don’t uproot plants and trees in the oasis, as they have done in the past.

One of the delights of the palmerie is the cool shade it provides, even in the midst of blazing sun:

The middle layer of the palmerie–fruit trees–is much more closely interwoven with the palms than I had expected: here’s a fig tree entwined with the base of a (badly pruned) palm, and a pomegranate very near by.

Aziz stops to greet an elderly man. In his youth, he was called Karim (the word for generous), but his nickname now is simply Aki.

Aki is busy working his garden, located behind a head-high pisé wall. He invites us in to take a look. In fact, the first thing he does is climb a big palm to pick us a few lingering dates. I hope I’m half as agile when I’m in my 80s.

The date season is already mostly over by early November, but there are 26 varieties of dates in the oasis, and there are always a few somewhere that are slow to ripen. These are premium dates, Aki tells us, and they are indeed the best tasting dates I’ve ever had: enormous and sweet and juicy.

Each year, as a good farmer does, Aki prunes back a lower layer of palm “branches;” this means you can read the age of the tree by counting the rows of pruned branches up the trunk. Some varieties of palm have tightly spaced branches; others are more loosely spaced. As a result, the height of the palm doesn’t tell you the age of the tree: you need to count the pruning rings.

But date palms are only part of the picture here: there are fruit trees (including olives) around the edges of Aki’s garden,

green fields of mint and (nitrogen-fixing) alfalfa (with some loose-leaf cabbage–this is the preferred variety of cabbage in the south),

and beets and peppers and eggplant, oh my!

Every time I admire a plant, Aki promptly harvests one and hands it to me: note the large bag of loot I am accumulating. When he hears I’ve got a stomach bug, he finds a variety of celery that he says will help, along with more verbena.

Then he wants to show us the oven built into the side of a wall: he shows us how he hangs, say, a leg of lamb inside the oven, with the coals below, and then banks it to cook slowly for two days. Then he grins at us: it’s a good photo here! Aziz, take their picture!

Laden with food, we leave Aki surveying his garden (built on the space where a house once stood) and head back out into the more open spaces of the oasis.

Water is everywhere: this palmerie is incredibly rich in water, flowing under bridges made from palm trunks.

The al-bayud fungus threatening the palmerie is treated by cutting down infected palms and burning the surface : the fungus lives on the outer layers of the trunk, so the inner trunk can be used for construction purposes.

One of the things I envy most is the remarkable ease and simplicity of irrigation here: a few stones, a handful of mud, and gravity. It certainly beats bucket and hose.

Deep beds (rather than raised beds) allow for deep irrigation, flooding for a few hours at a time:

Even if the irrigation is easy, though, the labor is still hard. I remember Eric Ross drilling it into us: an oasis or palmerie is an agricultural system, highly productive but incredibly labor intensive. Aziz has been telling us that the older generation know how to work all day long without getting hot or tired; the younger generation has lost this knack. Here, for instance, the older man is wearing a djellaba and long sleeves, while the younger man is stripped as far as is decent.

Pruned palm fronds make a fence defining a family’s plot. Nothing is wasted here. Even the date stems, stripped of the dates, can be used for brooms, as Jeremy demonstrates:

This half-harvested plot is also one of Aki’s fields, Aziz tells us. He’s one of the most productive farmers in the oasis. This is a field of mint, left perennial. He harvests it to take the mint to market (for the essential Moroccan mint tea); by the time he’s reached the end of the field, the beginning is ready to harvest once again. I’m amazed it rebounds so well and so quickly–but then, it is mint, liable to be invasive unless handled with tough love.

There’s an interesting mixture of the traditional and the new in the work of the oasis. Note the dangling earbud on the man driving the donkey.

After touring the oasis, we went to visit the abandoned village above the fields. The pisé buildings with the mountain behind are very evocative of the American Southwest, aren’t they?

Inside, we see more of the palm trunk floor/roofing, and also the upper layer of the house. I’ve been wondering about why people have moved out of these traditional buildings in such droves, but Aziz’s explanation clarifies things for me: not only is there no running water, but the traditional mode of living included larger domesticated animals (donkeys, sheep) on the ground floor, then smaller animals (chickens, rabbits) on part of the upper floor where the family lived.

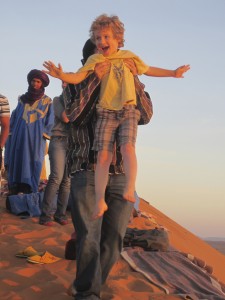

The village offers a lovely warm spot for baking in the sun during colder winter days: Zoë decided to clone herself so part of her could stay here.

We leave Aziz at the Poissons Sacrés cafe and drive out of the gorge toward the desert. On the hill above the palmerie, you can see both the fertility of the oasis and the aridity of the landscape surrounding it:

The contrast underscores the near-miracle of oasis productivity–and the precariousness of this life in an erratically warming world.

The contrast underscores the near-miracle of oasis productivity–and the precariousness of this life in an erratically warming world.

We were so glad we did! The “map of Africa” is the formation’s claim to fame,

We were so glad we did! The “map of Africa” is the formation’s claim to fame,