The road south from Ifrane to the Tafilalt oasis is marked by a beautiful stream that always lifts my heart,

more commonly by dry river washes,

(where water remains, somewhat surprisingly, just a foot or so below the surface), and perhaps most consistently by the evidence of remarkable geological forces at work:

.

.

If you’re six, however, the road is punctuated primarily by sandwiches and animated videos:

Thank heavens for well-equipped friends! It’s a long road.

We’re tagging along on a trip with Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI), the culmination of their 7-week sojourn in Morocco, doing an integrated field study project. John Shoup, anthropologist, and Eric Ross, geographer, both of Al Akhawayn University (AUI) are leading the trip. (Both photos lifted from the internet: apologies.)

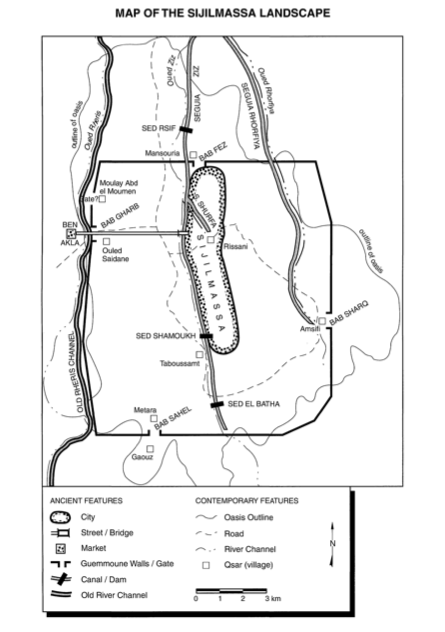

We’re headed to the Tafilalt oasis and to the site of a powerful medieval city, Sijilmassa.

Sijilmassa was once one of the most powerful urban centers of the Maghreb; one medieval chronicler [Mas`udi] claimed it took half a day to walk Sijilmassa’s long main street. The eleventh-century writer Edrissi described it this way:

As for Sijilmassa, it is a big and populated city, visited by travelers, surrounded by beautiful gardens and fields inside and outside [the ramparts]; it does not have a citadel, but it consists of a series of palaces [ksur], houses and fields, cultivated along the banks of a river coming from the Western side of the Sahara; the floods of this river, during summer, resemble those of the Nile, and its waters are used for agriculture in the same manner as those of the Nile are exploited by the Egyptians. [qtd in Iliahane (2004), 40]

I’m a little obsessed with Sijilmassa. It seems to me that the vicissitudes of this vanished city are somehow central to the aspects of Morocco I find most baffling: the nearly miraculous creation of a nation on the edge of a desert; the (disputed) segmentation of Maghrebi society, with Arabs, Berbers, Jews, “blacks” and other foreigners remaining quite distinct despite general insistence on social pluralism; the perhaps-related silence around race; the reverence accorded the king; the role of Islam in public understanding of the nation.

Bear with me, if you will, as I look into the history of the region and the city in a series of related posts, focusing (albeit not in any particular order) on (1) irrigation technologies (for building or maintaining oases in the desert), (2) Sijilmassa’s founding and social history, (3) agriculture or permaculture: the growing patterns of the palmeries, (4) the religious institution of the zawiya, (5) the architecture of a royal qsar in relation to local resistance to French colonialism.

References:

Dale R Lightfoot & James Miller, “Sijilmassa: The Rise and Fall of a Walled Oasis in Medieval Morocco” in Annals of the Association of American Geographers 86:1 (Mar 1996), 78-101.

Hsain Ilahiane, “Ethnicities, Community-making, and Agrarian Change: the Political Ecology of A Moroccan Oasis” (University of America Press, 2004).