The day of visiting teachers in Telouet is a study in contrasts: the movie studios we pass on the road out of Ouarzazate both opposing and imitating the villages themselves; the teacher’s thumbdrive serving as an unexpected counterpoint to his improvised, plastic-covered blackboard, and so on.

Here are some highlights of the trip:

School 0: On the road into the first small village, we pass a gaggle of children on the road. The tallest boy in the group runs to shake hands with Hassan out the driver’s side window. “Hassan used to teach in this village,” Ahmed explains. “That boy was one of his students.” Clearly, Hassan was a beloved teacher. Still, I wonder why the children are not in school this morning. At this first stop, we don’t even get out of the car. There’s a small school on the left and a small residence up the hill on the right. Hassan calls to the children in the school, but there doesn’t seem to be a teacher present. One of the children runs up the steps to bang on the door. After five extended poundings, Hassan calls him back, laughing. Enough is enough: either the teacher is not present or he or she is not in a state to meet with us. Hassan restarts the car and we drive on.

School 1: As Ahmed asks the teacher, Lahcen, about the needs he would like to see addressed in the next training session, Hassan talks to some of the children, trying to help the little girl nearest me to see where she went wrong with the math problem in her notebook. What Lahcen most wants is a way to use the materials Hassan and Ahmed are bringing (a set of picture books and children’s magazines) to really develop a love of reading in his students. It’s a central issue: how to make these materials come to life for the children?

School 2: We stop at a preschool where the teacher who’s been participating in training has now moved onto a new placement in Rabat; her replacement asks eagerly whether she could participate in the training instead.

School 3: A husband-and-wife team divide the upper classes: Abdulrachman teaches French, and Hayat teaches Arabic. Only during this visit do I realize that the school day starts around 8:00 and ends at about 12:30, with a break at 10-10:15; after the break, the children who have been studying with Hayat go to work with Abdelrachman and vice versa. In most of the schools in this area, education continues to be split evenly between Arabic and French, with the students speaking Tamazight at home. In this context, my limited Arabic and non-existent Tamazight make me feel like a slouch.

The walls of Hayat’s classroom have posters about H1N1 and others proclaiming Allahu akhbar: God is great. I’m struck by the mix of state religion and hygiene. Hayat is wearing a bathrobe, as are some of her students, for warmth; she’s just had a tooth pulled, and still suffers pain in that jaw. But she’s sharply focused on the books and the discussion of pedagogical needs. She is looking for activities that children can do independently for a sustained period of time, to enable her to intervene more directly and extensively with those children who are struggling.

As we are leaving, Hayat addresses me in a mixture of French and English, and we end up talking about family. It turns out that the teachers have a four-year-old son and eighteen-month-old daughter. The children sleep until 10, when Hayat runs home to make breakfast for them before coming back to teach the second half of the morning. I hope there’s an adult home with the children as well, and I assume there is, but I don’t want to ask. Still, I’m struck by the lack of margin in Hayat’s life, the pressure to be teacher and mother, even though I’m sure she also celebrates the opportunity to fill both roles as fully as she can. I’m missing my children as well, as we climb back in the car for the next extended drive down the rough piste.

School 4: We wait for the teacher to come back from lunch. The director of the school invites us to sit in his office, and eventually tea is produced. Hassan and Ahmed take the opportunity to ask whether the teacher we’re waiting for has been sharing her new resources with other teachers at the school. “Not really,” the director replies; pressed for detail, he specifies: she hasn’t shared software or library books or teaching techniques. Ahmed recaps the conversation for me while the director goes off in response to a different teacher’s request.

“That’s not good,” I respond, somewhat indignantly. “It’s a good thing you found out. People shouldn’t hoard resources.”

“Yes, but perhaps she didn’t understand what we were asking of her,” Ahmed replies gently, and I stand reproved. When will generosity come as my first response to other people’s actions?

When Sukhaina arrives, in fact, she is full of energy and ideas. In the past training, she appreciated Lotto as a way of teaching students categories of French vocabulary. What she most wants from this next training is a demonstration of different learning games: she wants her students to learn by doing. Asked about what she’s done to share what she’s gained from the workshops, Sukhaina is quick to say that her fellow teachers haven’t been interested in learning what she’s been taught, and Ahmed quietly but firmly clarifies: even if the other teachers are not interested, you need to take books to them, you need to demonstrate the software or describe a new teaching strategy in staff meetings. Work with your director: he’s keen to extend the read of the training.

School 5: We spend quite a while at the next school: Ahmed goes off to talk with the director of the school and Hassan and I hang out in the preschool class. Some seventeen 3-4-year-olds sit at two long rows of tables; another 4 children sit on a rug at the side of the room. The teacher is working on Arabic: she’s drawn a stick figure on the board, and the children repeat the fusHa (or modern standard Arabic) after her: femoon, nefoon, eienoon, oudnoon. It’s odd to hear this formal-sounding language coming out of these tiny mouths.

Hassan focuses his attention on Leila, a three-year-old deaf girl. She’s tiny, engaging, just on the almost-manageable side of hyperactive. When it’s Leila’s turn to go to the board, the teacher has her point to the stick figure, then stroke the relevant part of her own body: modified signing. Hassan calls a boarding school for the deaf in Ouarzazate: a school where he used to work. The director there agrees to talk more with Hassan about Leila’s case, and the two try to set up an assessment for Leila. Her best hope, Hassan thinks, is to go to the boarding school, even at age 3. There’s no instruction for her, and almost no potential for communication, in her home village. In the not too distant past, deaf people have been physically abused (Hassan’s word is “tortured”) in Morocco.

School 6: Ahmed tries to call ahead, but when we arrive, the teacher is nowhere to be seen. “Moroccan mobile phones!” Ahmed jokes. “Even when you talk to the person, the phones don’t work.”

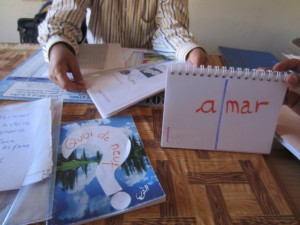

We sit in the director’s office and Hanan arrives, along with tea and little tea cookies. I’m particularly impressed with the teaching books and materials Hanan has produced. Talking about digital stories leads into a conversation about how much the children enjoy doing plays with home-made puppets. She also shows us the story books her older children have produced–and the flip books she has made to help her students understand components of French words (syllables, prefixes, suffixes, etc.)

Bonus school: As we near the road back to Ouarzazate, we pass a new “community school” that has only just opened. The idea here is that numerous small villages will send their children to this one larger community school. The school is designed to hold some 80 boarding students and about 200 day students. The whole place is spanking clean and new. The students are practicing for an inaugural ceremony: they are singing the national anthem. Hassan and Ahmed know everyone here, from the gardener to the director. Everyone gives them a hero’s welcome.

I’m struck by the fact that Hassan and Ahmed vanish briefly (sequentially, leaving someone to keep an eye on me) to pray. We started the day at 7:30 in the morning; we were given some bread, butter, olives and honey at about 10 a.m.; it’s now 5 p.m. One of the phrases from the dawn call to prayer (or just before) is this: “It is better to pray than to sleep.” I think of this now: for Ahmed and Hassan, it seems, it is better to pray than to eat. I am terrifically impressed with their dedication, their good humor, their attentiveness, their focus. When I try to tell them this, they laugh. “We work harder than Americans!” they exclaim, wonderingly. It becomes clear that they are trying, quietly, to transform their country, to compensate for their countrymen and women who are not working as hard as they might. Education is the key to the transformation they desire: a world of possibility and hope for all.

.

.

Sama straightening out one of my many confusions…

Sama straightening out one of my many confusions…