It’s all about the ramparts. The waves breaking on the rocks just beyond, the rows of sombre cannons facing the sea

(even if the only thing left to aim at is a stray seagull).

(even if the only thing left to aim at is a stray seagull).

The fabled isle of Mogador lies just offshore, amid the crashing waves, on the far side of the smaller Iles purpuraires (the purple islands): this one with the fort is Dzira Sghira; it was disarmed by the French when they bombarded the town in 1844.

The Phoenicians established some trading posts on Mogador, or the iles purpuraires, back in 1100 BCE (Amazigh tribes had been fishing in the bay for a couple of thousand years before that). In about 600 BCE, the Phoenicians established the settlement of Migdal, or watchtower, on the island now known as Mogador. Then, in 500 BCE, Hanno the Carthaginian visited Mogador and established the trading post of Arambys.

Starting in 25 BCE and lasting until about 300 CE/AD, Juba II established a Tyrian purple factory, processing murex and purpurae shells found in the intertidal pools between Mogador and the mainland

into precious purple dyes used to color imperial Roman senatorial togas. (Tyre is a city in Lebanon where these dyes were also produced.) Tyrian purple was valued in part because the color was supposed to improve rather than fading with age.

Phoenicians, Carthaginians, and Romans: oh my!

I want to go find a tidal pool, but this seems challenging. In the meantime, James chooses a cannon, ready to repel an attack from the sea,

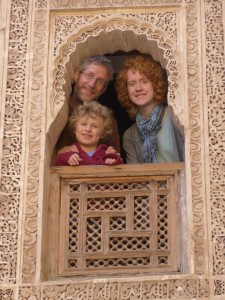

and we encounter our Ifrani friends, the Dye family.

Jeremy, Zoe, and I climb the tower to peer down on things from above. Beware incoming seagull!

The town was known as Mogador until Mohamed III had it rebuilt by French and Genoese architects and builders and renamed it Essaouira (little fortress souira, or well-drawn picture souera). The name Mogador may come from Migdal, or from the saint Sidi Mogdoul whose shrine is here (he was reputedly a Scot–MacDougal–shipwrecked on the coast, and endowed with baraka). The French changed the name back to Mogador, but independence brought a return to Essaouira.

Baraka Mohamed: maybe some of it will rub off on us.

Jem and Zoe pose in the circle close to the entry to the ramparts.

But it looks a little different from the other side, in the evening light.

That’s one of the interesting things about Essaouira: it’s both a tourist center and (still) a fishing village, even though the fishing industry has suffered in recent years.

As tourists, we enjoy the wandering musicians (whose music Zoë hopes to share),

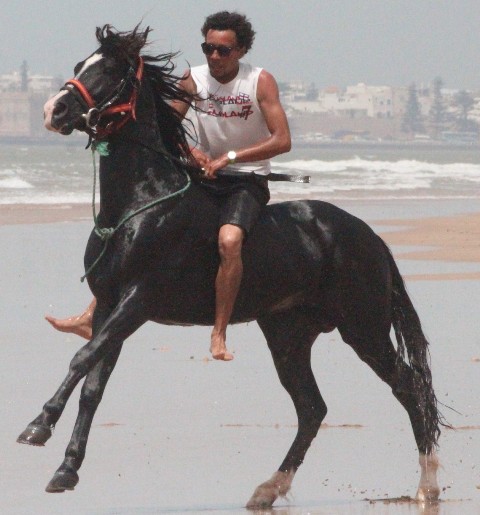

and we go horseback riding on the beach in the afternoon.

and we go horseback riding on the beach in the afternoon.

I like talking with our guide, Brahim. He sits on his horse so comfortably, kicking a leg over now and again: half the time, it looks little like he’s lounging on a sofa.

“Were you a jockey?” I ask. He’s got the physique and the professional comfort level. Brahim nods.

“Did you get hurt?” He nods again. It’s a stupid question. All jockeys get hurt.

“Break some bones?” Nod. Enough already, Betsy. It’s like picking at a scab–I can’t quite stop–but at least I can stop with the personal questions.

photo Zouina cheval

“Where is there racing in Morocco?”

Marrakesh, Rabat, Casablanca, Tangia: all the major cities. The responsibility for organizing the year’s racing rotates among the cities, so each one takes a turn. Ibrahim rode for an owner with a large stable–nine jockeys. But then the owner married a French woman, moved to France, and sold all his horses. Ibrahim was a little unsure what to do next. He came to Essaouira to meet a friend at the Gnawa music festival–he’s also a musician, in his spare time–and he discovered Zouina Cheval was in need of a manager. He and the boy leading Jeremy run the stable, just the two of them. Ibrahim likes it better than being a jockey–likes talking with the tourists, meeting people from all over the world. He has a wonderful face, with wise eyes.

photo Zouina cheval

photo Zouina cheval

Brahim only worries when the riders are a mixed group, like us. “Your son is doing well, but sometimes the children cry. I worry they won’t be happy.”

We too were worried that Jeremy would be unhappy–but now I only worry for the young man leading Jeremy. Jeremy is as happy as can be–and demanding as well. “Vite! Vite! Ma mère a dit wakha, c’est bon.” Jeremy mingles French and Darija like a Moroccan. “Fast, fast! My mom said it’s ok, it’s good.” The young trainer gets his boots splashed by a sudden wave, and runs up the sand. Jeremy laughs and laughs: “Encore! Dans la mer! Encore!” Again! In the sea! Again!

Nancy and Jeff look very professional–Nancy says it’s her first time “running” a horse. She did beautifully.

J and Zoë and I splash through the surf with Mogador in the background. Visible on the island are the mosque and a women’s prison, now defunct, originally built by Moulay Abdelaziz in 1897 to lock up rebellious member of the Rhamnna tribe.

Here are two photos of the prison from http://www.essaouira.nu/mogador_island.htm (a great resource): first, “Berber prisoners” sent to this prison by Moulay Abdelaziz,

and then a view of the four gates constituting the only way in or out of the prison.

The structure had no roof. Prisoners evidently had to take the rain or sun as it came.

By contrast, this sunny, breezy afternoon on the beach feels like such a luxury–as indeed it is. It turns out that we’re in Essaouira during the non-windy time: the wind blows constantly from April through September. Brahim tells tall tales, of the village down the coast where every house has two doors. All summer, the wind blows from the north and villagers use the southern door. All winter, the wind blows from the south, and villagers use their northern doors. (The town now hosts a wind farm, so there’s definitely an abundance of wind.)

After our ride, we head back to Essaouira, which is gleaming in the evening light. The juice sellers here decorate their stands with what strike me as orange “scalps” (sorry):

And the fishermen are hard at work, preparing their sun-bronzed boats for the next day or week or month:

À vendre: for sale. Fishing boat, anyone? Or shall we settle for supper in a bag on a bike?

At evening, the seafront is full of hidden corners,

And the sunset heightens the magic of the iles purpuraires:

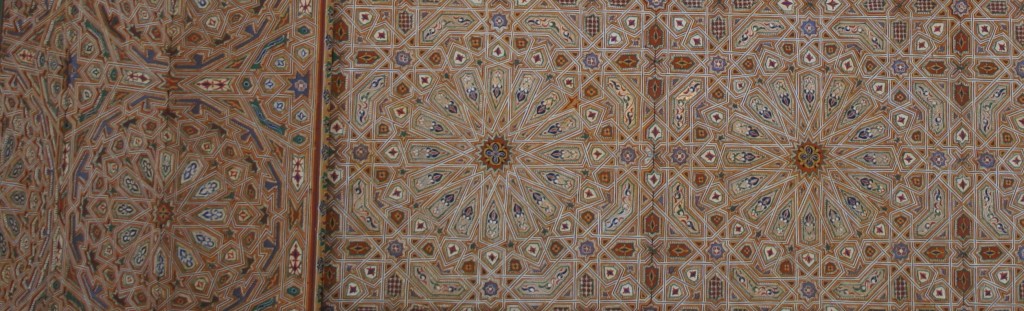

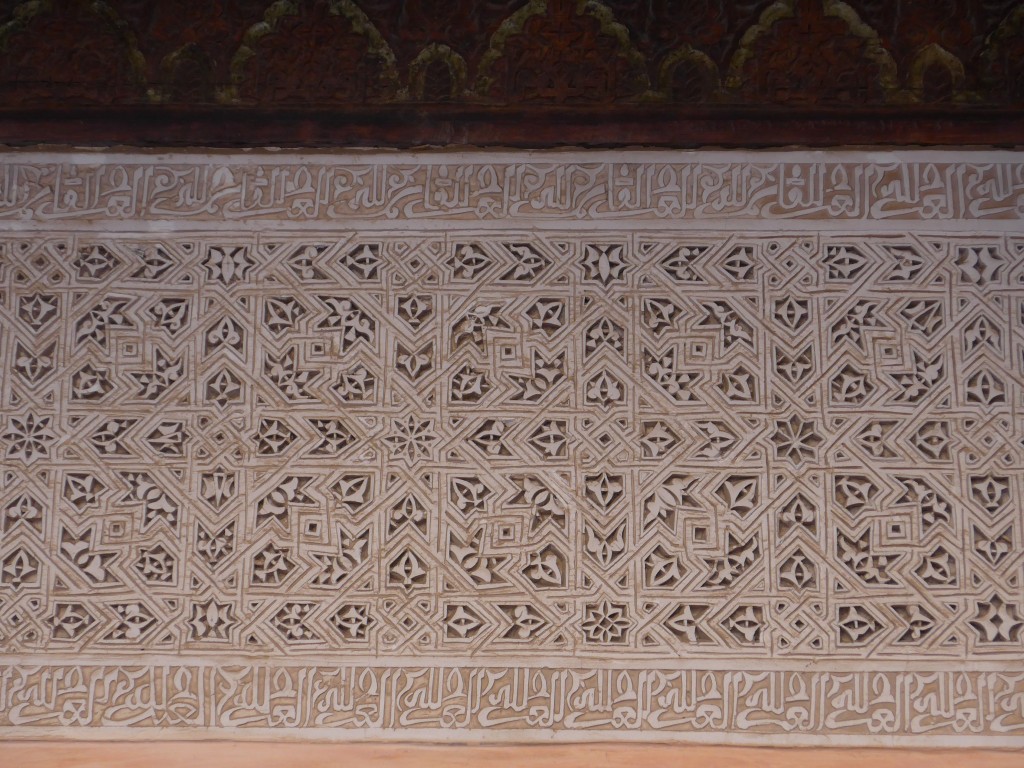

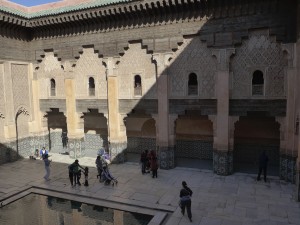

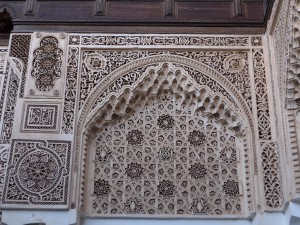

As with the Meknes Bou Inania, you could see that students would have been tightly packed into these rooms.

As with the Meknes Bou Inania, you could see that students would have been tightly packed into these rooms.

plus an example of an ancient oil press, with technology even more “beldi” or traditional than what we saw outside Demnate:

plus an example of an ancient oil press, with technology even more “beldi” or traditional than what we saw outside Demnate: