The Almoravids founded Marrakesh in 1062 (four years before the Normans landed in Hastings, England), but the only architectural remains are this small shrine or Koubba (qubba), half hidden by the streets of the city rising up around it:

The shape of the crenellations can be found throughout the middle east and North Africa; their origins are lost in time. Along with the keyhole arches, the dome, the decoration over the dome, these architectural details will carry forward into Andalucian architecture.

The Almohads, who succeeded the Almoravids, destroyed most of the city, including the mosque, the foundations of which were not properly aligned with Mecca. But they rebuilt the Koutoubia mosque, with its fabulous minaret:

Towering above the medina, the Koutoubia minaret glows from dawn to dusk, orienting the entire city.

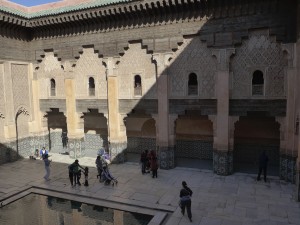

The Marinids were major builders in Marrakesh, looking back to the Almohads with their Medrasa Ben Youssef, a Quranic school attached to the Ben Youssef mosque.

But the Saadians embellished on the Marinid work, both in redoing the Ben Youssef Medrasa and in creating the famous Saadian tombs.

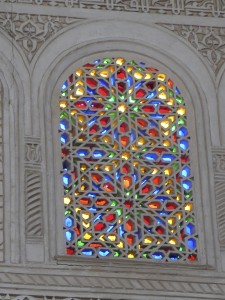

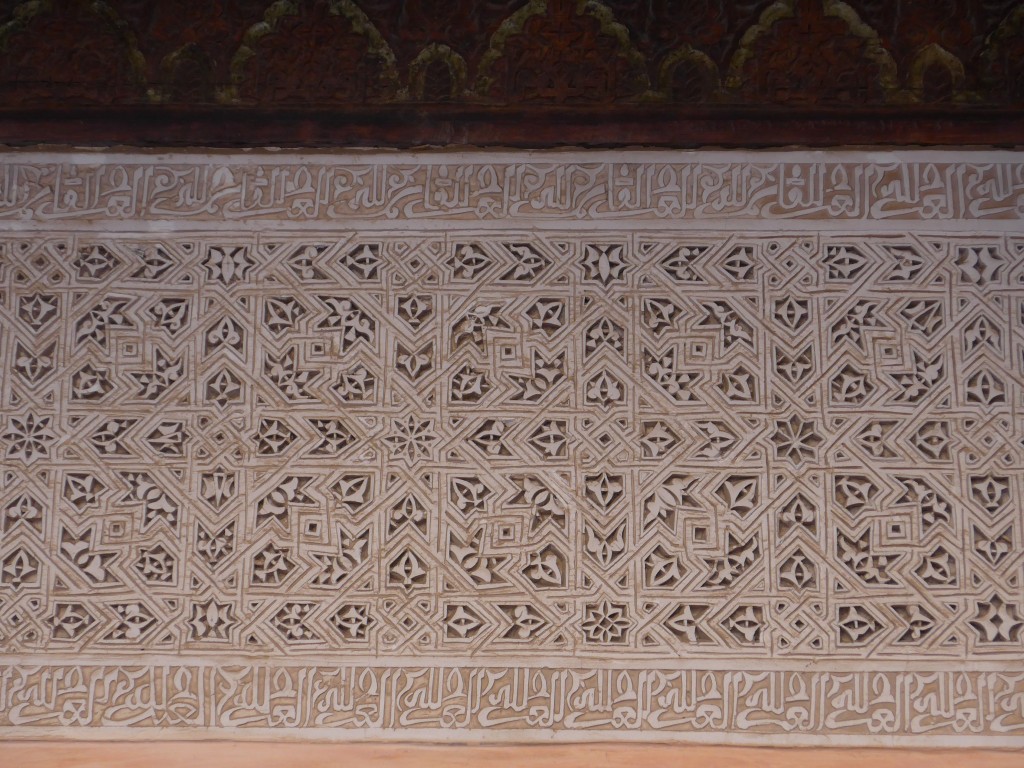

We loved the Ben Youssef Medrasa. I liked the way the zellij played with slightly different patterns than the ones we had seen in Fez and Meknes.

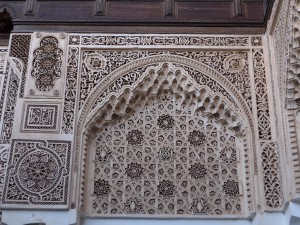

The plasterwork also stood out, both for its coloration (reflecting the colors surrounding and defining the “Red City”) and for its more severely geometric patterns (at least in some parts).

We wondered about the source of this cedar in Marrakesh: was it brought all the way down from the cedar forests around Ifrane, or was there a closer source, in the High Atlas?

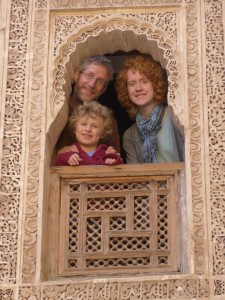

The courtyard was peaceful, empty at certain moments, filled with quiet tourists pushing strollers at other moments.

But what we liked best were the student quarters, with all their corridors and quiet nooks.

The rooms were arranged around a number of separate courtyards, each with its own access to the sky, each with its own collection of resting birds (?) if you look closely enough…

As with the Meknes Bou Inania, you could see that students would have been tightly packed into these rooms.

As with the Meknes Bou Inania, you could see that students would have been tightly packed into these rooms.

But the living quarters were a little less dilapidated than those of the Bou Inania, and James with his public school (boarding school) background, said that he could feel the spirits of the boys who had lived here, looking on in bemusement as we (and thousands of other tourists) wandered through their haunts.

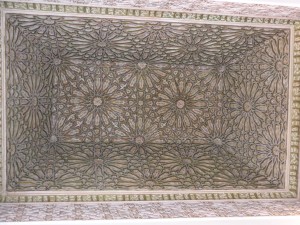

At the other end of the medina, the Saadian Tombs, built by Ahmed Al-Mansur, were famously walled up by Moulay Ismail. Even now the entry is through a narrow corridor that Jeremy found a little spooky. The gloomy grandeur of the Chamber of the three Niches is hard to capture in a photograph,

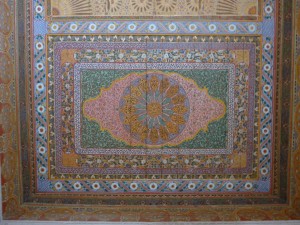

but I could have spent hours gazing at the ceiling alone:

.

.

The mausoleum for Al-Mansur’s mother is drenched in light and thus easier to grasp, somehow.

.

.

My favorite detail: the carved wooden khatems high above one side entrance, almost lost in the honeycomb pattern defining the arch…

It’s as if they’re floating in space.

Jump forward in time several hundred years to 1860, when the grand vizier Si Moussa began the Bahia Palace, further embellished by his son Abu “Bou” Ahmed. Bou or Ba Ahmed was born to a slave woman, and he himself was dark-skinned, but he rose to become vizier or chamberlain to Hasan I, who succeeded in reunifying much of Morocco after years of disruption. After Hasan’s death, Ba Ahmed arranged for his younger son Abd el-Aziz to become sultan; Ba Ahmed ruled for six years as regent until his death in 1900 (he’s believed to have been poisoned). Various stories told in the Djemma el Fna tell of a black slave becoming sultan, presumably with the story of Ba Ahmed in mind. During the Protectorate, Thamis el Glaoui occupied the Bahia palace.

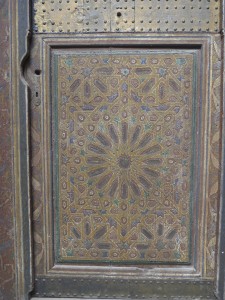

The zellij at the Bahia palace is still interesting and intricate, as is the plaster…

but the artwork I found most compelling was the zouaq, or the wood painting. Some of this remains in older styles and colors, but the influence of European aesthetics begins to be seen in different color palettes:

The ceilings in particular were mind-boggling in their detail and precision:

But the palace overall was defined by its age: an age of complex negotiations with European powers, as seen in this Europeanized aesthetic: