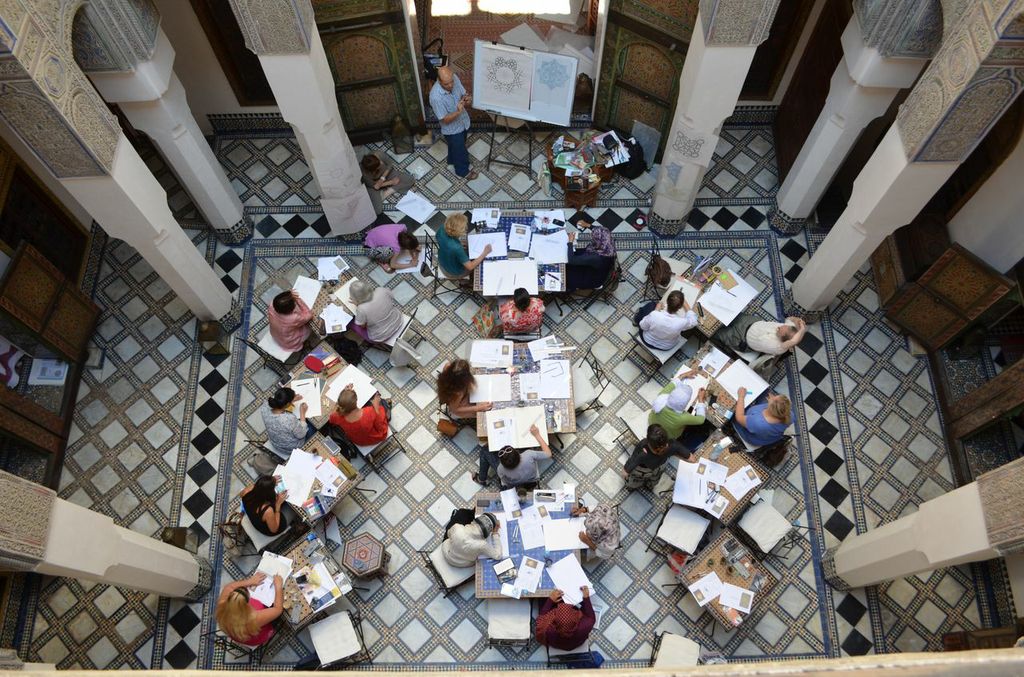

In this post, I’m trying to reconstruct a presentation given by Alla of Dar Seffarine, an architect originally from Iraq, but now a long-time resident of Fès. Alla and his wife Kate own the guesthouse Dar Seffarine; Alla also specializes in reconstructing traditional houses in the Fès medina, so he has thought deeply about the architectural features of the typical Fassi house.

Imagine these words as spoken by Alla, as he gestures towards the features recorded in the photos. (All errors, of course, are mine–and the first photo is actually of David Amster showing our group an entry to a derb, where the door and the guardian would have been located.)

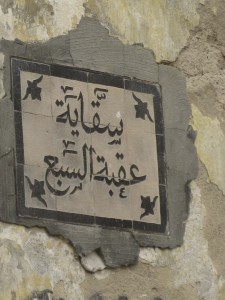

Alla: Every derb, or residential street, should have a door at its beginning, and that door should be watched by a guardian. The guardian will ask of each visitor: where are you going? who are you coming to see? how long will you stay? Only in the past 60-70 years has the tradition of the doors been lost, the doors themselves sold, the guardians unemployed. This entry (to Dar Seffarine) is actually the door to the street. Since there are only two houses on the street, the government lets us maintain the street door between us.

The riad is the garden (visible just through the window above the right-hand door); the house or dar exists just beside the garden. A duera is a small house connected to another house: servants’ quarters, housing the servants and slaves who served the family of the dar.

When you come to the house proper, you will notice that the door that opens for daily use is on the right side. You use your right hand to open the door. All this emphasis on the right hand comes from the Quran, which teaches that the right hand is the good hand.

The door opens to the inside of the house, and you find yourself in the corridor. Every house has a corridor: it is an essential part of the house. Sometimes, the corridor is only a meter long; sometimes it is much longer and has a door at each end; but all traditional Fassi houses have a corridor. To be polite, you stand in the corridor as your host goes into main part of the house and tells the women to leave, that a guest will be entering.

Notice the square holes down at foot level: these are ventilation for the basement. Fassi houses have basements, with columns and arches, where one can escape the heat of the summer. Some houses, you enter, and then go four or five steps down: again, the principle is to use the cooling available below grade.

Also in the corridor, you may see windows to the street: this will help with ventilation.

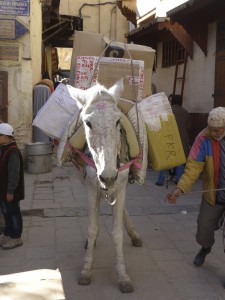

The street itself may be roofed (as seen in the second photo of this post) to create a tunnel to help move the breeze through the space.

Above your head, you may see a boxed in area. This is a storage space for taxes, or zakat, the charitable giving obligatory in Islam. At the end of Ramadan, each household had to give 1.5 kilos of flour to the poor [multiplied by some factor, it seems to me—bb]. That boxed area made it possible for householders to buy the flour when it was cheap, store it, and then distribute it at the appropriate moment.

Immediately inside the door to the house, you see another door, leading to an internal staircase: this allows the man of the family to visit one of his wives without the others having to know. Separate doors for separate wives: this minimizes conflict within the family.

On the wall in our corridor, we have hung the contract of sale for our house. As you can see, this is a large document, recording the most recent three sales. The three pages—one for each separate sale—are bound together. Every time the house is sold, the oldest contract is removed, and the newest contract connected to the document.

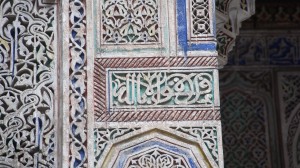

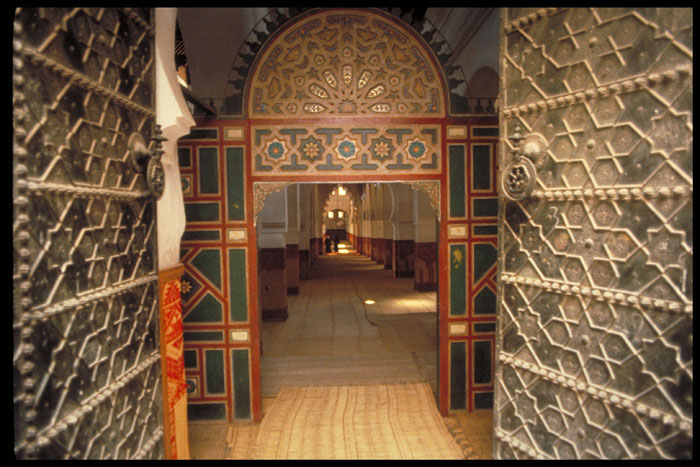

At the end of the corridor, we have another door—a door within the door. The larger door allows for large items to enter or leave the home; the small door, for everyday use, forces the person entering to duck. You must enter the house with respect. When you have stepped through the doorway and you straighten up, you raise your eyes to the calligraphy opposite, which reads: “All this belongs to God” or “There is no power but God.” This saying counterbalances pride in the owner of the house and envy in the visitor.

Finally, you find the courtyard on your right. You will never enter a traditional house directly: always, you turn to discover the house, the central courtyard.

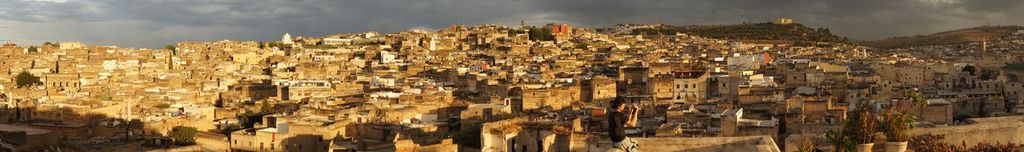

That courtyard is open to allow for gradual cooling overnight. Houses in Fès were single-storey buildings originally. Seffarine’s small minaret tells the story: the minaret must always rise above surrounding buildings, but today that minaret is dwarfed by the houses and buildings around it. Originally, the houses would have been a single story, but as the city grew and wealth increased, homeowners expanded their houses upwards, building additional living quarters around the existing courtyard.

On either side of the courtyard, two salons face each other: one salon is for family use; one is for entertaining guests. This salon is a man’s space.

Above, there is a mezzanine for the women’s use, where the women could sit and listen to the men’s conversation without being seen.

[BB: From the inside, the mezzanine is fabulously decorated with ornate zouaq–painted wood–but it’s a small space, too low to stand in. Definitely only a space for sitting on the floor and listening.]

The norm in domestic architecture as in more monumental or sacred spaces, is to decorate the floor and lower areas with zellij, tiles in complex geometric patterns; above the zellij comes plaster (often plain, then carved), calligraphy (in plaster or tile), and then carved or painted wood. Dates in houses are recorded in terms of the Hijra or Islamic calendar–a lunar calendar starting with 622, the year Mohammed moved to Medina–and they normally just register the date the most recent plaster was finished.

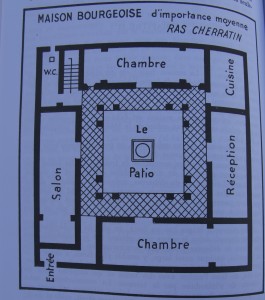

To complement Alla’s presentation, here’s a map of a traditional Fassi house before the Protectorate from Roger Le Tourneau’s book:

Here you can see the stairs, the bathroom, the kitchen, and the entryway. But what stays with you after a visit to Dar Seffarine is the glory of that courtyard, lifting the eye to wonders overhead.

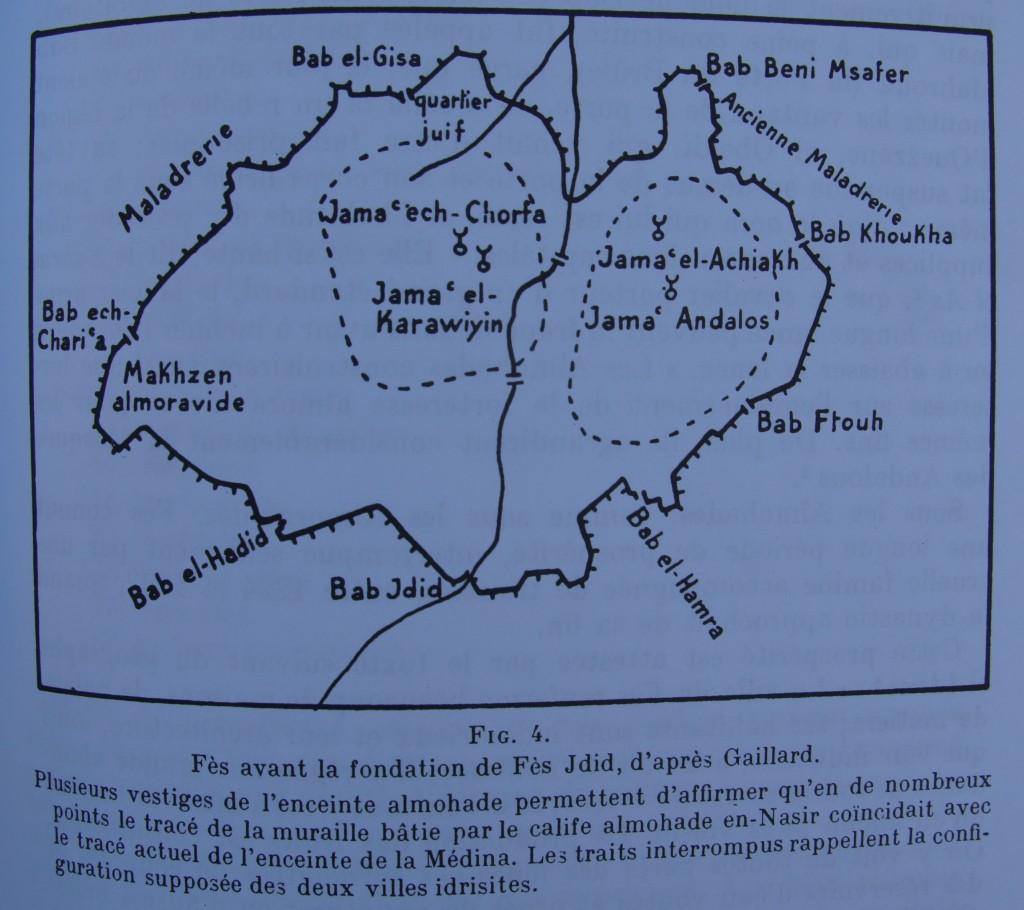

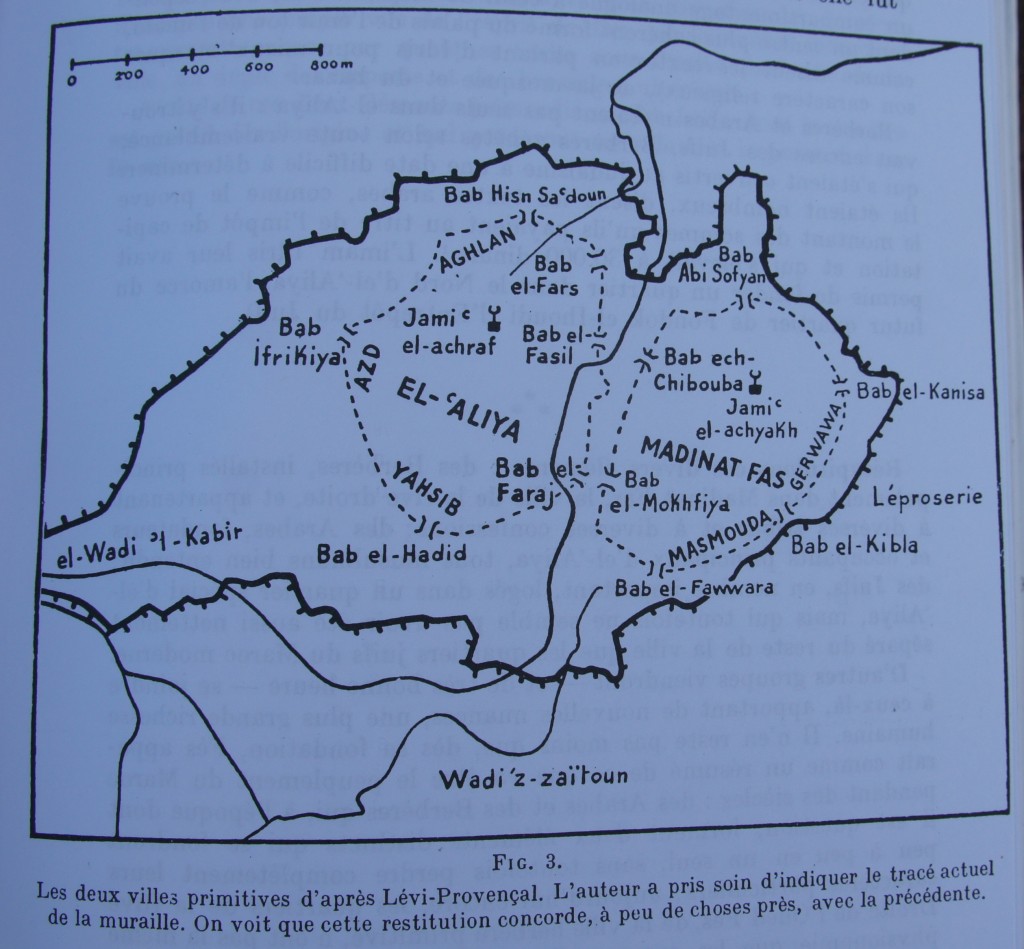

Notice the important rivers (wadis or oueds) running between and around the two towns

Notice the important rivers (wadis or oueds) running between and around the two towns