I realize the word “fossilizing” refers to the process of becoming a fossil, but a day of fossil-hunting left us feeling (almost) desiccated and condensed enough to qualify.

We started out at Brahim Tahiri’s fossil museum where we met Abdelali, our guide for the day. “Today, you’re going into the Devonian and Ordovician,” Brahim told us. Zoë and I grinned at each other, enjoying the thought of traveling into geologic time periods. I had hoped for an English-speaking guide who could drill us in the differences between Ordovician and Devonian (for instance), but Abdelali had hardly any English or even much French, and he preferred to speak to James, often not hearing when I tried to ask a question in Darija. So here’s what I’ve dug up since our trip:

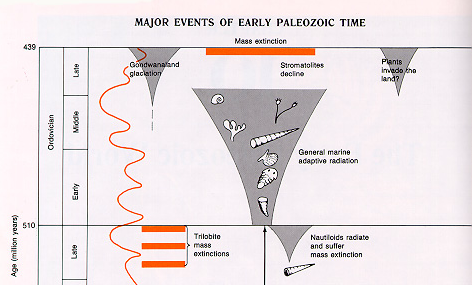

(see earth.usc.edu)

The Ordovician period precedes the Devonian. According to this USC website, the Ordovician period lasted from about 510 million years BCE until about 439 million years BCE; it was marked by a huge increase in biological diversity, during a time when all life remained in the oceans. Life flourished and developed in a warm climate, with reefs providing niche conditions favoring diversity. The end of the period is marked by a mass extinction in which over 100 families went extinct, probably due to earth cooling beyond the comfort range of organisms that preferred warmth.

One of the most remarkable things about the Ordovidian period is that North Africa was located over the south pole at this time:

(see earth.usc.edu)

(see earth.usc.edu)

Wacky. Whose idea was that? Points to them for thinking outside the box.

The Devonian

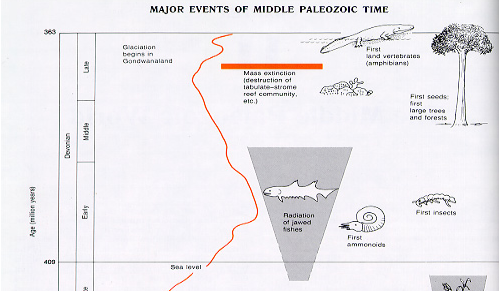

(see earth.usc.edu)

The Devonian was the beginning of the world we know: the first seeds, first land vertebrates, the first time life emerged from the oceans. But there was still a lot of life in the ocean–life that registers now in the fossils remaining in this section of Morocco. Note the mass extinction defining the end of the Devonian, like the mass extinction defining the end of the Ordovician. We’re in the middle of a mass extinction today as well. What new period is coming our way?

After loading up Abdelali’s 4×4 with some water, bread, and oranges, and La vache qui rit (packaged cheese), we drove out into the hammada, also known as the “black desert.” We turned off the road out of Rissani along this long line of peaks, a place where the earth looks like a breaking wave.

Along that piste through the hammada, there are two distinct veins of fossils, running parallel to one another. In the first, fossil miners have dug cave after cave in order to excavate plates of fossils from a layer of sediment some 10-20 feet under the surface.

Once the plates of fossils have been identified and chipped out of the substrate, they are assembled, a little like a jigsaw puzzle, on the surface near the mining pit.

These fossil plates seem to feature crinoids: creatures that in a fossilized state look vaguely like octopi. Or, as Zoë noted, trees.

(photo Zoë)

(photo Zoë)

According to the Bonnachere Natural History Museum,

“The Crinoids’ soft body was protected by several hard plates which formed in a bowl-like shape. From this came tentacle-like arms, which were used to gather food. It was fixed to the sea floor by a long flexible stem consisting of many discs. Once the crinoid died, the discs were scattered over the sea floor.”

There are also lots of little pieces of something that might be cephalopods?

Abdelali kept using darija words that seemed to mean tentacles or branches, and every time I started talking with one of the miners (most of them had some English), Abdelali wanted to hustle us away, probably for monetary reasons…

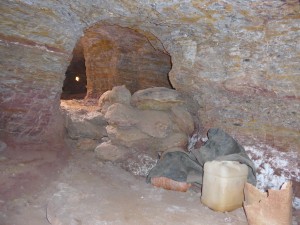

The work is daunting. In the deeper pits, or those with stronger sides, miners dig ladders into the side of the pit. Elsewhere, they seem to rely on a rope held by a colleague. Notice the miner’s feet and back tucked into the passage on the right. Talk about claustrophobia!

Earth is removed from the pit by means of a pulley system, in some cases run off a solar panel.

Down in the mine: all the comforts of home?

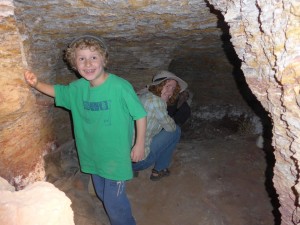

We went down into one of the mines: one with a collapsing set of steps down the side instead of a vertical ladder.

Hard to imagine working down here with any kind of precision. Imagine the endurance, the psychological strength, required to crouch here, chipping away in solitude day after day.

You have to look past Zoë’s hat to see me, down at the rock face. And the light comes from a camera flash, so imagine the normal conditions. We were glad to come out again.

But the miners themselves don’t have any such quick and easy exit. It’s cooler beneath the surface during the heat of the day, but it’s parched out there. Workers bicycle along the rough piste; some seem to live next to the mines, in a couple of rough huts, perhaps as night guards? No one seems to mind us scrabbling around in the slag heaps, looking for fossils…

We walk over to the second vein of fossils–featuring orthoceras!–where we pick through more slag heaps left by what looked like earth moving equipment. Instead of carefully constructed pits or caves, there seemed to be large scoops dug out of the earth, and piled alongside the worked vein.

Orthceras were a little like the squid of the Ordovician world. We find both (nearly) complete creatures, and little cross-sections.

In the black or grey stone, they make me think of shooting stars, as if the residue of this little squid were a path through the stone, light through the darkness.

In the black or grey stone, they make me think of shooting stars, as if the residue of this little squid were a path through the stone, light through the darkness.

Jeremy found a lock, which he enjoyed flinging through the desert air; his parents loaded up with fossil finds…

It was hot out there, even though spring is still a week away. After a few oranges (too many seeds! we’ve been spoiled by tangerine season!), some water and a few hunks of bread, we drive to a different fossil site. This is on the scree slope just under the crest of a small mountain. We’re looking for trilobites, one dominant species of the ancient ancient world.

Let’s face it: we’re wimps. Jeremy was wanting to go back to the hotel, even before he fell and scraped both knee and elbow. James fell also and scraped his arm, though he didn’t notice the damage till a few days later. And the trilobites were harder to find: tiny points of evidence suggesting a larger creature buried in a rock. James eventually got enthused, finding possible trilobite geodes just under the rocky outcropping capping the hill, and Abdelali clearly knew what he was doing, but I went back to the car with the children for another drink and nibble and a look at the Erg Chebbi dunes not too far away.

We persuaded a reluctant Jeremy to hang on for one more site: this involved driving past what appeared to be a local garbage dump, complete with goats and birds. We think the goats must know better than to eat plastic–or else they have very strong constitutions and the plastic doesn’t bother them.

Past the goats and the garbage, we climbed a slight elevation with the desert stretching out below in both directions.

Jeremy perked up when he got to hold a hammer. Finally, a real paleontologist’s tool!

J looked like he was having fun, too:

But then we were pretty well done for the day. We went back to the Tahiri museum, where we took another look at the process of preparing the fossils for museums and private collectors. The reconstruction of a large plate of fossils:

The first pass at chipping away the stone surrounding a trilobite:

Polishing:

Closer detail work:

Trilobites were amazing! Such a range of forms, improvisations on a single basic shape. Eyes made out of something like shale. Impossible curvatures, impossible protuberances. And the world they came from is almost unimaginable to me–though the world we’re heading into may be almost as unfamiliar.

Still, the thing I learned most clearly today was how hard it is to be a fossil miner. What I may remember most vividly (other than the heat, the thirst, the isolation) is the extent of the desert as seen from our little elevation–or the way the hills we drove along at the start of the day seemed to remember the waves of the ocean that once covered them.