People kept telling us that the southern route from Erfoud to Ouarzazate or Marrakesh was much slower than the northern route (don’t trust Googlemap times in Morocco!), but we’d been on that stretch from Tinghir through Kelaâ M’Gouna and Skoura too many times, so we decided to test out the alternative for ourselves.

The road was fine to start with, lulling us into a false sense of speed. Then we hit kilometer upon kilometer of potholes. But the landscape was so stark and compelling, we almost didn’t mind.

Ruined ksour on a cliff above a palmerie; solitary figures walking or riding through a barren landscape–almost too stereotypically Moroccan–but very striking.

We had decided to break the journey in Tamnougalt, just shy of Agdz, at Chez Yacob. Yacob himself turned out to be a major highlight of the journey (see next post): fluent in English, a long-ago collector of traditional tales (back in 1992), a superb and delightful host, and a key figure in a nightly jam session of traditional music.

We arrived mid-afternoon and started with a tour of the still-inhabited mellah of Tamnagoult. Texture, texture, texture: surfaces were rich and evocative everywhere we turned. From the carefully detailed brick mantel over the entryway…

to the stark simplicity of corridor walls, the nearly crumbling pisé construction of an inner courtyard or the arch of that entry…

to the stark simplicity of corridor walls, the nearly crumbling pisé construction of an inner courtyard or the arch of that entry…

to the eloquent surfaces of daily objects,

or the architectural imagination that turns a brief glance into a (re)framing of the sky.

Because the mellah is still inhabited, there were signs of daily life: water bottles, mouths covered with lace to keep with water clean, and people working on the roof.

Because the mellah is still inhabited, there were signs of daily life: water bottles, mouths covered with lace to keep with water clean, and people working on the roof.

One courtyard seemed to feature more Andalusian style arches; another had lower arches and presumably ceilings:

At the chef’s room, where local court cases would be heard, the walls were tadelakt, burnished with egg whites, and the ceiling was in Berber style:

J was intrigued by the traditional lock, all made from wood:

There was a small museum, with examples of a pisé construction frame (with tampers),

There was a small museum, with examples of a pisé construction frame (with tampers),

and other items, like wooden supports for donkey saddlebags, a large-scale mortar and pestle, a “treasure chest” that delighted Jeremy, and a rather gruesome goat-skin used for making butter (someone would swing it back and forth to churn the cream into butter).

Many of the hallways were dark, but that made them feel all the more atmospheric, at least in the short term:

And the detailing of the windows at and near the exit was quite extraordinary. If you look closely, you can see a little hand at the top of the window on the right.

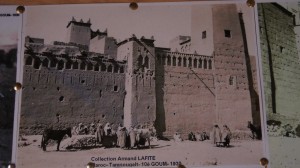

Our guide had his own collection of historical items: grindstones, oil lamps, sandals, platters, and so on–plus photos of the old community and of films that were made here:

After our tour of the mellah, we went wandering in the lovely palmerie.

I was struck by the wealth (a wealth of water, coming from the river visible in the top half of the photo) that meant pomegranates could be left unharvested,

with the result that songbirds were feasting, and filling the air with their song.

with the result that songbirds were feasting, and filling the air with their song.

Spring crops seemed to include peas and wild asparagus.

Fields of forage were also full of wildflowers, the air was scented with fruit blossoms, and the fresh leaves, especially of the fig, were incredibly green.

In the hour before dinner, I stayed with the children while James wandered up to the old kasbah, passing women and children and donkeys all carrying food and supplies back home.

As promised, the kasbah was an empty shell, but impressive nonetheless.

The palm-tree lintels seem to have been dug out for re-use, except in the long hallway where they’re still doing important structural work.

Overall, an interesting, but slightly spooky place, in which to watch the night come on.