When you spend two hours a day with someone, that person starts to feel a little like a friend or a family member. Youssef finds this easiest in relation to Jeremy. “Aji!” he calls to Jeremy. “Gliss!” (Come here! Sit down!) He pats the chair next to him emphatically. Jeremy looks at me sideway and I nod: yes, you need to go and sit down, at least briefly. Jeremy does so. Youssef then tries to carry on a one-sided conversation: “Ki deir? Mizian? Hamdullah! Sahebi?” (How are you? Good? Thanks be to God. Are you my friend?) I nod at Jeremy, and he obediently nods at Youssef. Friends. Youssef gives him a hug.

Before long, Youssef has raised the ante: “Khuya.” Jeremy is now his brother. (People on the street also call each other “my brother” or “my sister,” but in this context, it’s a little more intimate.) Before we came, I worried some about the famous Moroccan love of children. I wasn’t sure Jeremy would appreciate being loved by people he didn’t know well, but while he’s a bit timid at present, he’s taking all the love in stride. Still, he scrambles off to play again as soon as he thinks he can get away with it.

In many ways, Youssef seems more traditionally Moroccan than many of the people we meet here in Ifrane. Most Ifranis have at least moderately good French, for instance, even people who only made it through 3rd grade. Youssef has some words of French, but not enough to communicate clearly. (He doesn’t speak much English either, which makes it hard to ask about new words or concepts. And occasionally, the translations he offers head in the wrong direction: “God needs you” instead of “May God help you.”) Like “the country people” Ifranis describe, Youssef doesn’t change his watch with the official changes in time. (Morocco follows daylight savings time, but goes off DST during Ramadan, and then returns to DST at the end of Ramadan. We changed our clocks with the official time, but Youssef didn’t, with the result that for about a week he turned up an hour before we expected him.) Less traditional, I imagine, is Youssef’s passion for linguistics: he just finished a master’s degree on using technology to teach modern standard Arabic to foreigners; he’s hoping to start a new degree in Fez come the fall—perhaps a national doctorate (as opposed to an internationally recognized PhD).

In practicing vocabulary, Youssef and I talk about families and where we come from. Youssef was born in Errachidia; he lives with his two brothers in Azrou.

One brother is a greengrocer; the other sells furniture like Moroccan banquettes. Youssef occasionally drives a truck for this second brother, picking up furnishings from El Hoceima, for instance, on the Mediterranean coast, and grabbing a few hours on the beach in the process. Back in Errachidia, his father used to sell vegetables in the suq; he’s now retired. Another brother brings truckloads of produce from Agadir (on the southern Atlantic coast) to sell in Errachidia.

If I recall correctly, there are four brothers and three sisters in total. One of the sisters lives in Rabat; I lost track of the other two. But I’m struck by the geographical distribution of the family, given the importance of family within Moroccan culture. Still, one of Youssef’s nephews is going to marry one of Youssef’s nieces—Darija makes it clear that this is cousin rather than sibling marriage—a practice still quite common in Morocco.

Family vocabulary is very important in Darija, so it’s interesting to see what the structure of the language allows and emphasizes, and what it obscures. There’s no simple word for cousin, for instance: instead, one specifies the relationship through the older generation. A cousin is “son-of-a-paternal-aunt” or “daughter-of-a-maternal-uncle.” An American “blended” family is hard to describe in Darija. To talk about my much-loved stepmother, for instance, I have to refer to her as my father’s second wife, which has rather different overtones. Talking about my stepfather is a little more shady: “Your mother’s second husband?” (Really?)

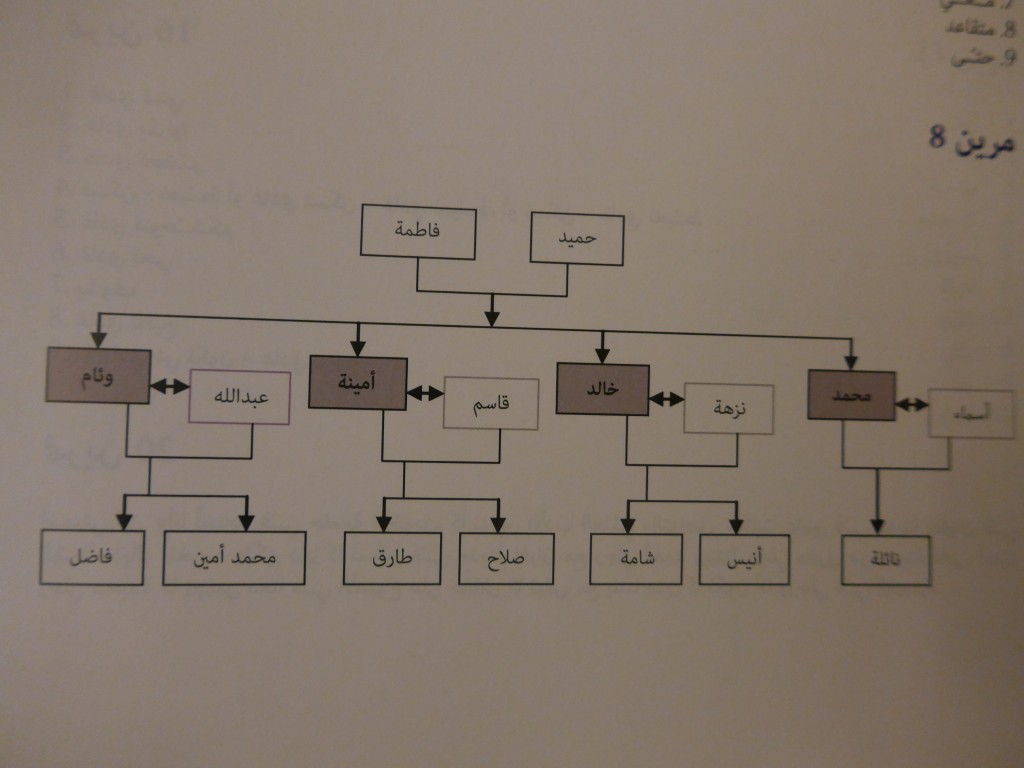

Youssef and I work on an imaginary family tree.

Fatima and Hamid are the grandparents; they have four children, two girls (Ouam and Amina) and two boys (Khalid and Mohamed). All four are married: Ouam to Abdellah; Amina to Qasm; Khalid to Nizha; Mohamed to Ismaa. I read the family tree from the wrong direction, left to right, taking the women ahead of the men. When I ask about terms like sister-in-law, Youssef points me to the mother-in-law relationship.

“No, I want to know how to describe the relationship between Ismaa and Nizha.”

“There is no relationship there. No word to describe it.”

“Really?”

“Really. Besides, they hate each other.”

“What do you mean?”

“This woman (pointing to Nizha) always hates this woman (pointing to Ismaa). At least if the brothers share a house.”

Ah, the light dawns. Brothers share the family house, and their wives are structurally in conflict with one another, struggling for dominance, disagreeing over how family resources and space should be managed.

Youssef isn’t done. “But the worst is this one.” He points to Fatima, the matriarch. “Both of these women (Nizha and Ismaa) hate her and she hates them. They must work for her, and she may be terrible to them, making trouble for them with each other and with their husbands. The older women are especially bad: no education, nothing in their life but the power to make their daughters-in-law miserable.”

Wow. I make a face at Youssef to show I’m a little taken aback.

He nods and grins. “You won’t find this in any books, but this is what I say. This is what I see. It’s not so bad now, but in the old days it was very hard.”

Talk about names within the family leads to a discussion of how affection is expressed. Parents are called by their titles: El Haj (marking those who have been on hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca, but the title is used more generally to indicate respect); a Lalla. Children kiss their parents’ hands; parents kiss their children’s (bent) heads. On the street, of course, there is the double kiss–cheeks pressed together on both sides of the face–and often an embrace, mostly between people of the same sex. Youssef imagines I want to know how to say ‘I love you,’ though I don’t think I’ve asked this. “The young people use ‘bgheet’ (the same as ‘to want’) but the old people don’t say this word. They show love by helping each other with burdens or giving a hand down a steep path, but they don’t say the word. The young people–it’s the opposite. They say the word, but they don’t show it!”

Youssef and I are very different from one another, and Youssef works, often visibly, to overcome the strangeness our family represents. When we invite him into a different part of the house, beyond the public area of the Moroccan salon, he pauses and then physically pushes himself forward into this inappropriate interior. When I bring up one of the famous secret prisons from Morocco’s “years of lead,” he startles, but again pushes on: “In this context” of tutoring, he states explicitly, “we can say anything.” The statement demonstrates openness and tolerance even as it marks a political gulf between us.

He’s happier to talking about the Green March, celebrated each November 4-6 in Morocco. During the Green March, some 350,000 Moroccans (escorted by 20,000 army troops) marched into the disputed territory of the (then Spanish) Western Sahara: they marched singing, carrying Qurans and Moroccan flags.

image from Morocco World News image from dynamicafrica.tumblr.com

“My uncle was a part of the Green March,” Youssef tells me, exultantly. “He was so happy: they were all so happy! Marching, singing! It was a wonderful time!” The Western Sahara, cannily annexed without bloodshed during this Green March, continues to be a vexed political issue, underscored by a 16-year war and ongoing conflict with the Polisario front, but it’s clearly important to Moroccan patriotic feeling.

When my tutoring sessions with Youssef come to an end, we take some photos to help us remember our time together.

Youssef wants photos with Jeremy and James; James insists on taking a photo of Youssef with me. I can feel Youssef’s discomfort despite Jeremy’s presence between us.

Once the photo has been taken, Youssef leaps away and then steps back to tell me I am like a mother to him. I would have chosen younger brother rather than son (is this vanity on my part or immaturity?), but I take his point. He has coped so well with this strange family, has worked diligently at this odd relationship with an uncovered, inappropriately dressed older woman. A lalla Betsy: Ms. Betsy. How do we resolve this odd, uncanny friendship? Through the model of family. Khuya: my brother. Umi: my mother.