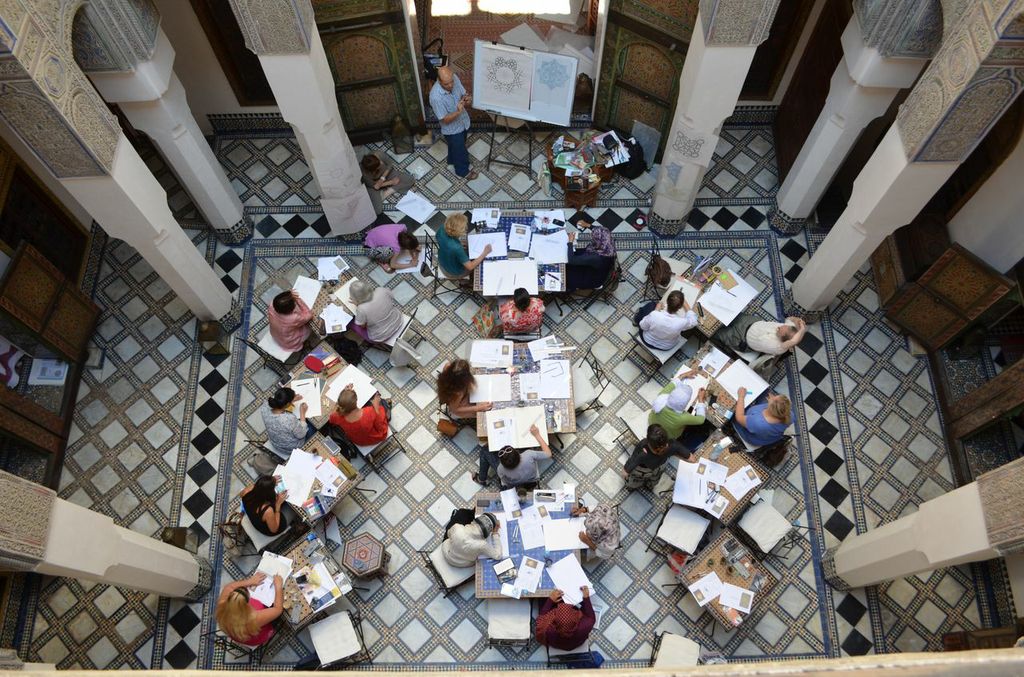

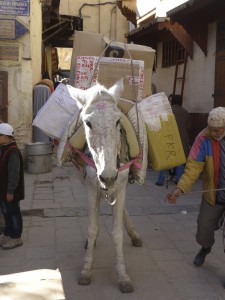

As part of the study tour, Jess Stephens split us into two groups and set up a series of visits with artisans working in the Fez medina.

Seffarine square is the brassworker’s square, with metal being hammered, joined, and heated. To make a brass pot, for instance, first the side is hammered out, then the base, then the two are joined.

Small pieces of brass and aluminum are combined to make the seam, then the seam is heated in an open fire:

Once the pot comes out of the fire, it’s beaten some more, to smooth and strengthen the seam.

Finished pots are lined with aluminum; they’re surprisingly light-weight.

Around the corner from the brassworkers is a quiet square known as Carpenter’s square, though there’s only one woodworker still present, urged by city government to remain.

He makes simple three-legged stools for other artisans in the medina; he can also make musical instruments, or even a peg-leg (a small model hangs in the doorway of his workshop as a way of clarifying specifications).

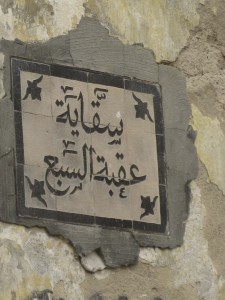

The dyer’s street (As-Sabbaghin) is also located near Seffarine square, along the river dividing the Karouine bank of Fes from the Andalusian bank. On a cool morning, the steaming pots of dying fabric have the feel of magic potions.

And it is a kind of magic, to watch the newly dyed fabric drawn up out of the bucket where it has been steeping:

Dark colors are died in hot water, light colors in cold water. These days the alum (to fix the color) is included in the dye. Traditional dyes drew colors from banana leaves, from henna, from kohl, from mint leaves, from zaatar (oregano).

Even the original silk is luscious, satisfying even just to look at: the colors gild the lily. The “silk” itself is imported from India, but it can also be sourced in Morocco from agave plants (sabra). Sabra silk is preferred to silk from silkworms because Mohammed banned his male followers from wearing gold or silk, but Sabra silk is a vegetable fibre, exempt from this prohibition.

The knife sharpening shops were not as picturesque as some of the other workshops, but here I had a sense of the ongoing life of the medina.

Everyone needs sharp knives and scissors, after all.

And the shop next store was well-stocked with the small motors that are used to twist the braids that are used to trim djellabas–and we had been ducking those twisting threads at various points on our wanders through the medina.

Fès used to have a public bakery in every neighborhood; people would make their bread at home, and then carry it to the public bakery to be cooked. Now, as more and more people have ovens at home, the public bakeries are becoming increasingly scarce. A pity, since the smell of baking bread wafting through the streets is pretty wonderful.

The horn-carver also seems poised on the brink of the past: very picturesque, but I suspect he survives mostly on purchases from foreign tourists. He takes a sheep horn, and straightens it with a vise to flatten it out.

Then he cuts, trims, and carves different shapes and utensils out of that horn:

The smallest shapes, like toothpicks, involved fine levels of sanding (and tough heels!):

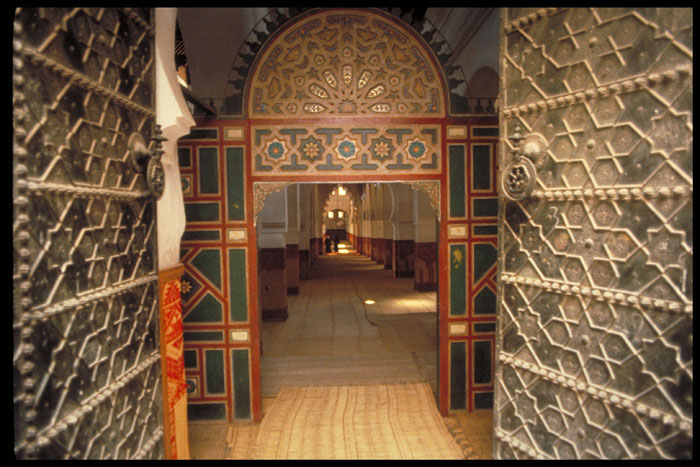

The metal embossing seemed most directly relevant to our study of Islamic pattern: the tools, the patterns, the geometric relationships.

The artisan had worked all over the world: Spain, the United States. But Fès is home.

Some of his work is drawn from patterns; other pieces he seems to know by heart.

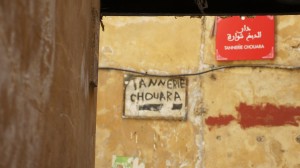

In early fall, by the time you see the sign for the tannery, you’ve already been smelling its potent presence for a while. Jess handed out squares of ambergris to sniff as a kind of antidote for the smell.

We started up in a shop overlooking the tanneries. Here you can get a kind of overview of the process: (some of) the pools of white are filled with chalk and salt, to separate the skin from the fur. Then there are the pools of pigeon droppings, to soften the leather.

The dying containers are filled with colors derived from vegetables: red from poppy, blue from indigo, tan from a combination of saffron and mimosa. There are no yellow vats: unadulterated saffron is so precious and powerful that the dye is painted directly on the pre-softened skins.

The men who work in the tanneries coat their bare legs and hands with olive oil to protect them from the dyes. (But I don’t imagine the work is good for one’s health.)

That was the overview. Then two of us went into the tannery itself for a closer look:

Lots of skins. If you can get past the corpse effect, you can see why softening might be desirable.

Painting the skin with chalk-salt solution just inside the entrance to the tannery:

Clearly, the work is physically hard; there’s also an art and a rhythm to it.

And a community among the tanners:

The dyed skins are laid out to dry on any available surface: rooftops, hillsides (near the Merenid tombs).

After drying, the skins are scraped with a half-moon shaped knife, to soften them even more. FInally, the carefully treated leather is cut and stitched into bags, shoes, belts, and other accoutrements.

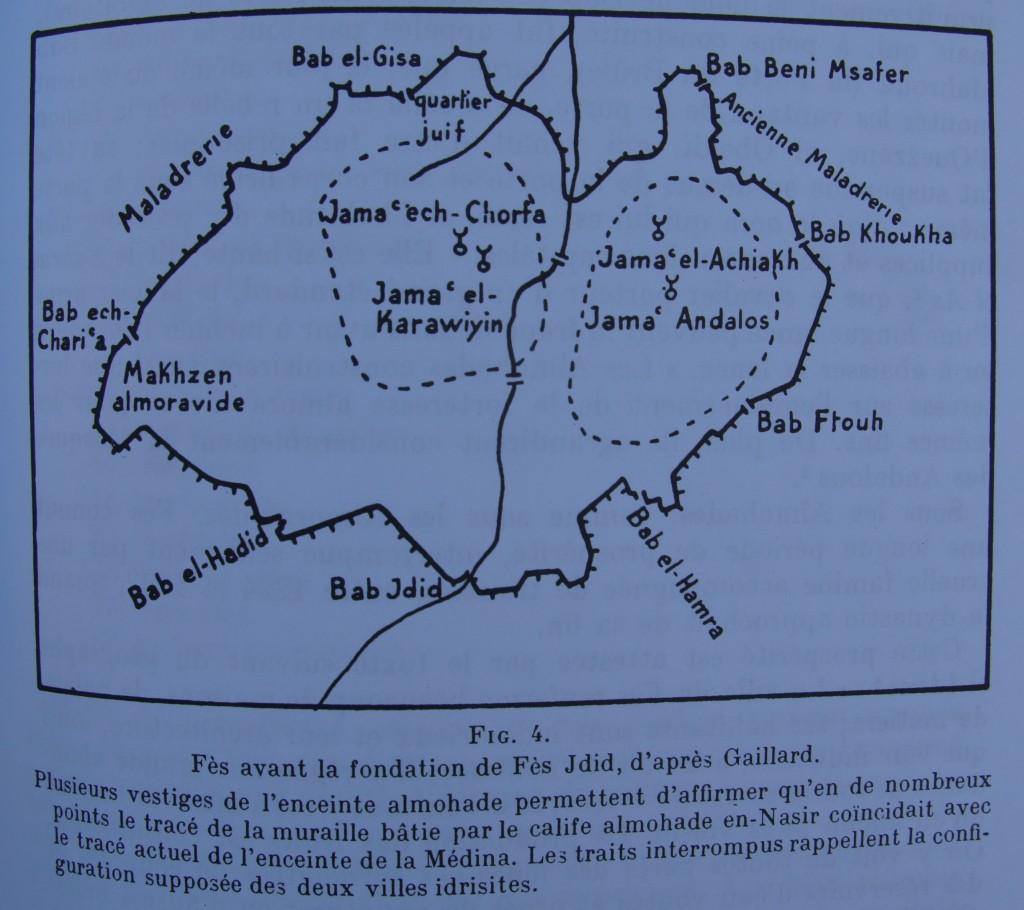

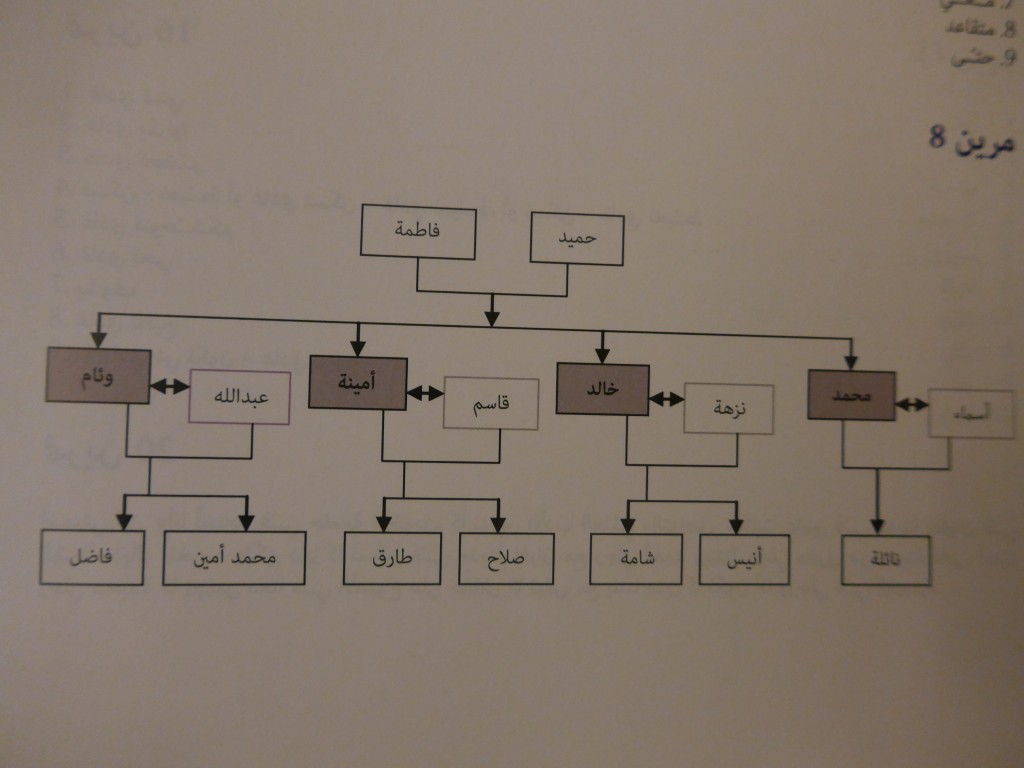

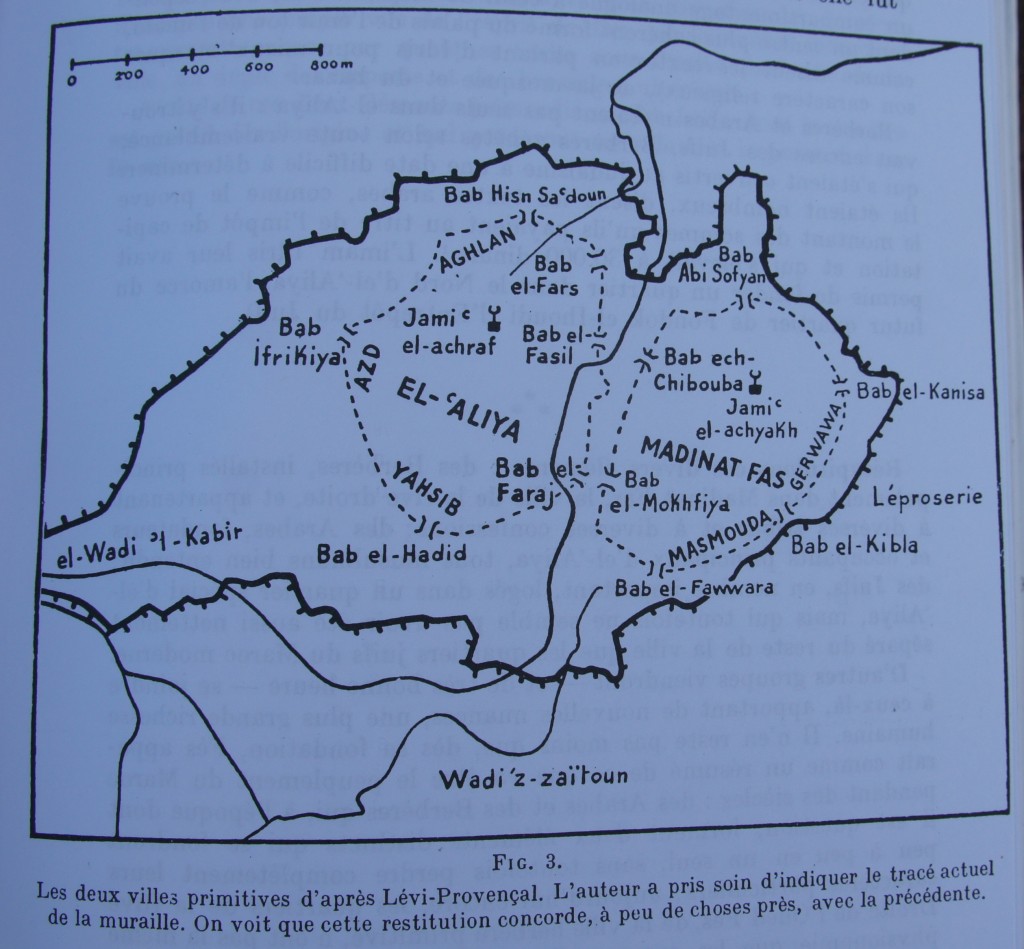

Notice the important rivers (wadis or oueds) running between and around the two towns

Notice the important rivers (wadis or oueds) running between and around the two towns