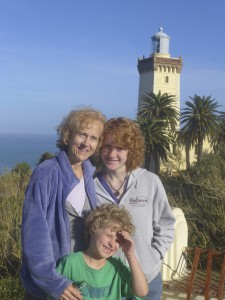

We’ve been to this site four or five times now, all told, but I’m going to make a single composite post, to try to unify our various discoveries and delights. The photo above came from our first visit, in early February. Wildflowers were already beginning to bloom in this lovely protected valley.

But the heart of this discussion comes from Zoë’s reconstruction of a late February tour led by Eric Ross and John Shoup. (James was out of the country, and I was leading digital storytelling workshops; Eric and John were astoundingly willing to let Zoë and Jeremy tag along with no parents to ride herd on them. ) I’m also including photos of some of the handouts used on that tour. When we returned in March with various family visitors, Zoë took on the role of tour guide. (Some strangers tagged along, too.)

I’m largely replicating what she channeled from John and Eric.

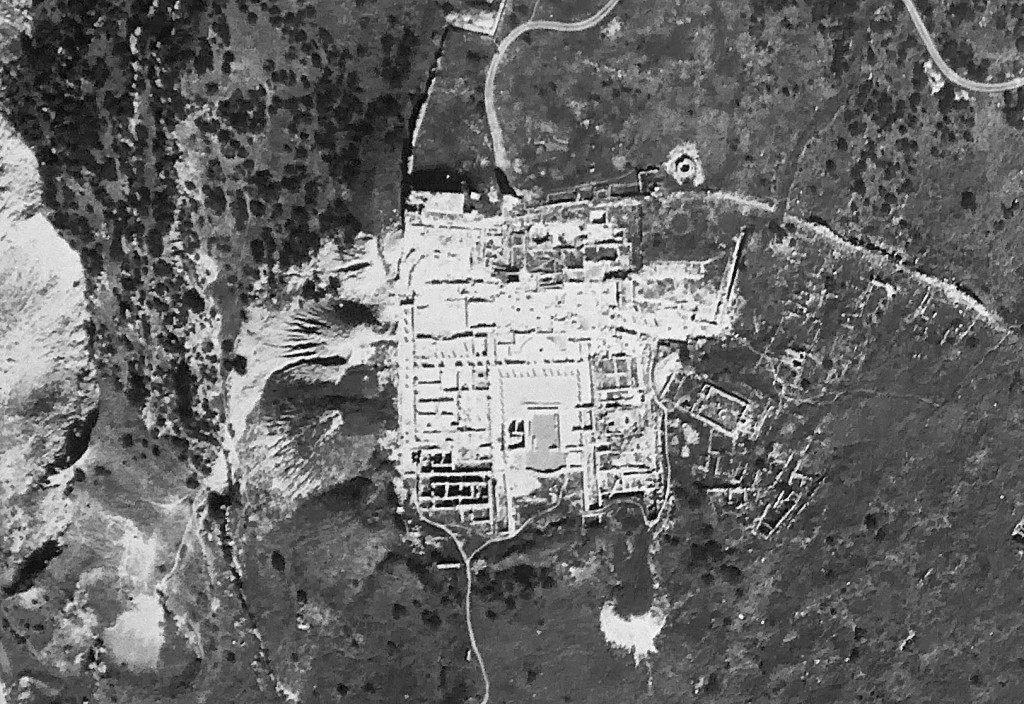

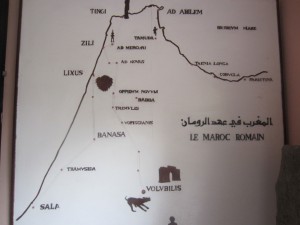

We should start by recognizing the politics of historical preservation. Many Moroccans feel no ownership of “Volubilis” because the French “discovered” the site as a Roman ruin. In fact, Walïlï is a palimpsest of settlement, with Phoenician and Carthaginian and Islamic construction bracketing Roman elements; all of these historical strands were shaped and informed by the local Imazigh people. (Timeline in French below notes the pre-Roman era, a brief Roman occupation, and a longer Islamicization of the city.)

Protectorate-era French excavated everything that came after the Romans and ignored everything that came before: Volubilis became a testament to the Roman Empire’s presence in Morocco, legitimating France’s imperial ambitions as the inheritor of the Roman empire. The massive gate at the bottom of the Decumanus Maximus, the main drag, is a bad or at least disputed reconstruction. These two aspects of the Protectorate approach to Volubilis seem related to me….

Of course Walïlï is a critical site of Moroccan history: the city where Idriss I was first sheltered by the Awraba, a Muslim Imazigh tribe, who shared this space with Christians and Jews. Fès, founded by Idriss I and Idriss II, is in some ways a direct extension of late eighth-century Walïlï, and all of Morocco looks back politically to the Idrissids as the first Moroccan dynasty.

OK, once we’re politically oriented, we need a sense of the site overall. First a map of the entire locale, in which the area on the right was the part of town dating back to Phoenician times, and the section jutting up on the northeast was the Roman extension.

And then we zero in on that Roman section with a map of the patrician’s quarters on the north-east side of the site.

The houses are labeled by what most clearly defined them, from the marble Bacchus found on site to the mosaics or olive presses that remain.

The houses are labeled by what most clearly defined them, from the marble Bacchus found on site to the mosaics or olive presses that remain.

Zoë led us up the north-east path toward the “cortège de Venus,” pausing to point out the hill that was probably once a meeting hall (behind the flowers).

Idriss I was eventually poisoned by the Abbasids he’d been fleeing when he arrived in Walïlï (conquering Tlemcen in modern-day Algeria made him too much of a threat), but he had married Kenza, daughter of the Awraba the chieftain Ishaq ibn Mohamed, and after his death, Kenza gave birth to his son, Idriss II. A canny strategist, Kenza saw that her son was threatened from many sides. She invited various rivals to dinner at this meeting hall and massacred them there. Evidently, when the hill was excavated, the right number of human remains were found to support this story.

The cortège de Venus offers an interesting example of surviving mosaics (which should be under cover rather than exposed to the elements), with a figural center and patterned border full of motifs also found in Imazigh weaving. The center of the mosaic shows the hunter Acteon surprising Diana bathing; horns are already sprouting on his head as he begins to turn into a deer, to be destroyed by his own dogs. Right across the (overgrown) street is an olive press marking the difference between this provincial city and imperial Roman practice. In Rome itself, an olive press would never be found in the city; rather, country estates would produce olives and press the oil which would then be shipped to the city. The base of the press here has channels cut to three separate depths, to channel different grades of olive oil in different directions. Next to the press is a (now overgrown and large filled in) stone container that WPI students measured at some vast capacity.

Right across the (overgrown) street is an olive press marking the difference between this provincial city and imperial Roman practice. In Rome itself, an olive press would never be found in the city; rather, country estates would produce olives and press the oil which would then be shipped to the city. The base of the press here has channels cut to three separate depths, to channel different grades of olive oil in different directions. Next to the press is a (now overgrown and large filled in) stone container that WPI students measured at some vast capacity.

To get to the front of the Venus house (or estate), you have to walk around the corner, onto Decumanus S.1. If you look down at the paving stones under your feet at the entrance to the house, you’ll see the space underneath the stones where water came into the house, providing water for cooking and cleaning and gardening in the garden at the center of the house.

To get to the front of the Venus house (or estate), you have to walk around the corner, onto Decumanus S.1. If you look down at the paving stones under your feet at the entrance to the house, you’ll see the space underneath the stones where water came into the house, providing water for cooking and cleaning and gardening in the garden at the center of the house.

To the side of the garden, along a corridor, were the family’s private rooms; close to the front were more public rooms where the paterfamilias might have met with other patrician men.

From that patrician house, we walked up to the Tingis (or Tangier) gate: a reconstructed gate built according to the instruction manual sent out with Roman soldiers across the empire. Can’t you imagine the soldiers cursing the engineer responsible for the drawings? “Keystone arch? Easy for him to say.”

The main gate would have been closed most of the time: people would have entered the city through one of the side gates, where their possessions could be checked and taxed by city guards.

Underneath the stones marking the center of the main road, the Decumanus Maximus, there remains a large channel that was once filled with the water supply for the city.

You can see the (large!) channel through some of the larger cracks in the stones. Moroccans and their water: so clever! Here, patricians have water delivered to their homes, at first; when the water stops flowing to these aristocratic estates, people move closer to the city center, where the water is used first for a public fountain, then for public baths, and finally for public latrines.

Was this part of the aqueduct?

Perhaps the most moving part of the entire site from my perspective is the public fountain at the center of the city, where the stone has been worn into long slow waves by centuries of women leaning over to draw water from the fountain.

Up the hill, meanwhile, across from the patrician houses was an early shopping mall, covered to ensure patrician wives would not find their shopping marred by an untimely rainstorm.

The small shops here, like hanouts in the modern-day marché or medina, would have had a shopkeeper at the front to fetch whatever his customers wanted to examine or buy.

A little further down the hill, we come to the building that houses “the labors of Hercules,” with the mosaic located behind the remaining triple arch on the Decumanus Maximus.

The triple arch itself is adorned with faces, the identities of whom I found but have since lost.

As the map below shows, the house itself would have been entered from the southwest, with entry-ways leading to the hall surrounding a central peristyle (columned porch or open colonnade) and a fountain.  Zoë is quite indignant about guides who not only tell tourists that the fountain was a bath but damage the remaining Roman cement of the fountain as they climb in to demonstrate the luxuries of bathing. The pink cement dates from Roman times; repairs can be seen in the whiter cement of recent history.

Zoë is quite indignant about guides who not only tell tourists that the fountain was a bath but damage the remaining Roman cement of the fountain as they climb in to demonstrate the luxuries of bathing. The pink cement dates from Roman times; repairs can be seen in the whiter cement of recent history.

At the end of the house closest to the street, we find a large Roman fishtank (cold water pool)–but these fish were kept in order to have a supply of fresh fishy food.

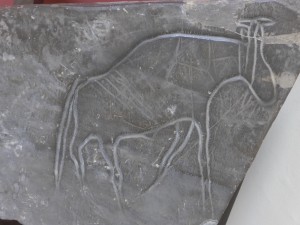

Most of the inhabitants of Walïlï are thought to have been Awraba (Imazigh) rather than Roman colonizers, a hypothesis supported by the base of the columns in this house. Roman Corinthian columns would never include a design like this at the base–and this design is a kind of fertility symbol, designed to bless the inhabitants of the house.

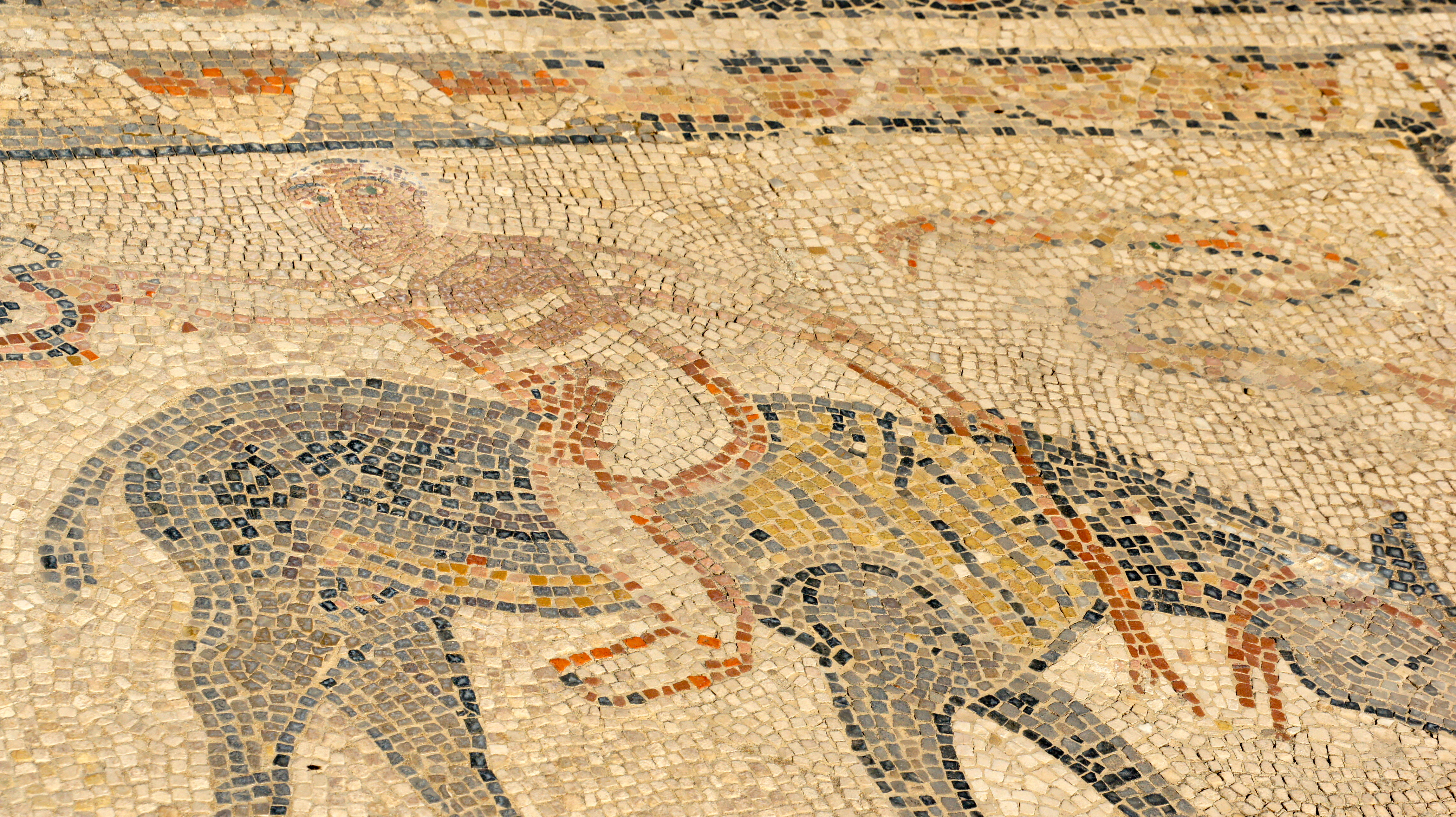

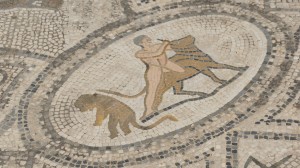

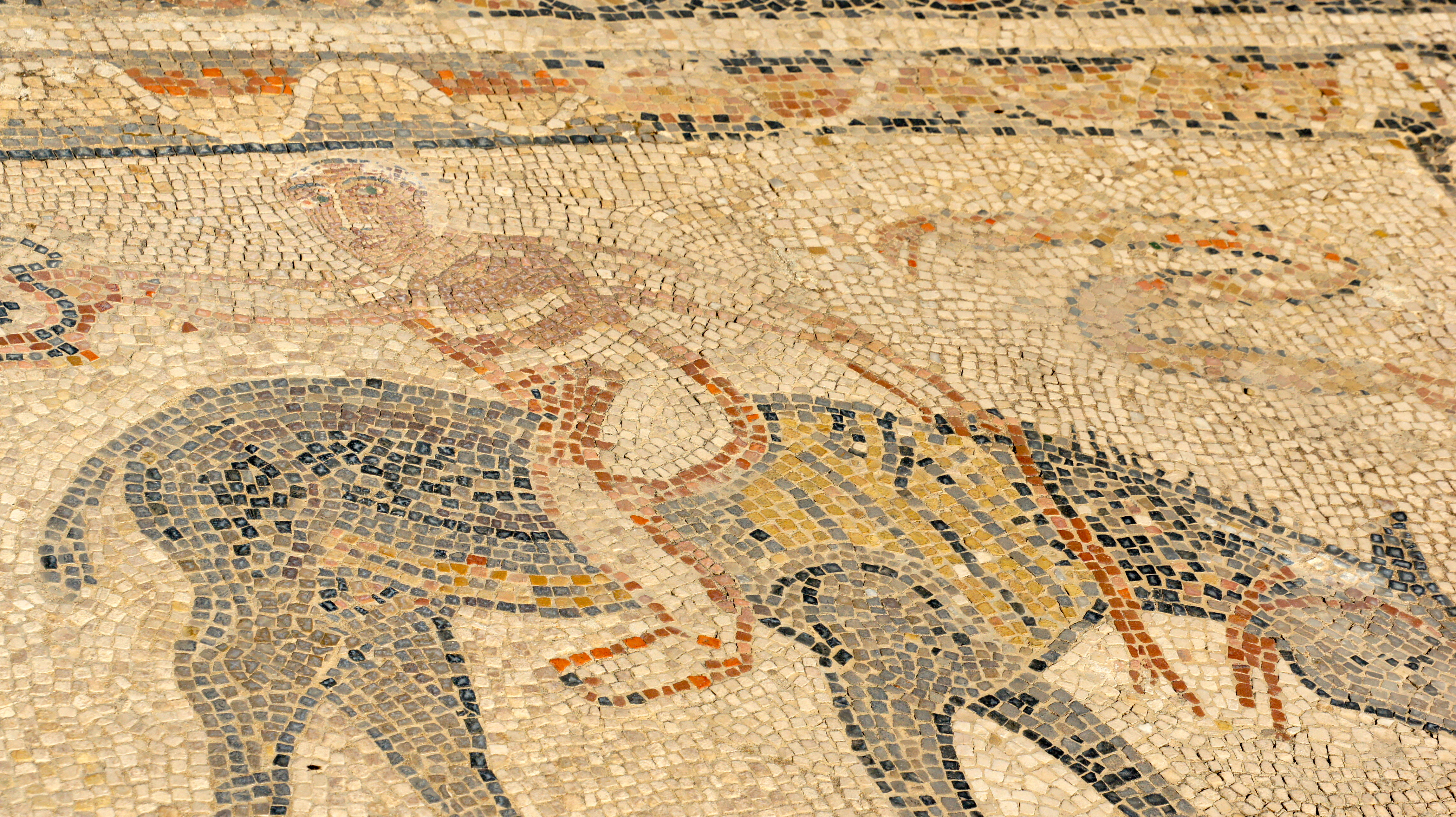

The “Labors of Hercules” mosaic is off in a side room: one would walk through the entrance, around the fountain, and into the room. Four portraits (two in good condition) occupy the corners of the figural section of the mosaic; each portrait is surrounded by flowers and bovine-looking patterns in a curved diamond shape, with four lozenges filling in the corners.

The outside lozenge (constituting the outer corner of the figural pattern) is a somewhat abstract shape; the other three represent the labors of Hercules. The complexity of these interwoven patterns is both impressive and pleasing–and that’s not even addressing the geometric surround.

The labors of Hercules included (1) killing the invulnerable Nemean lion,

(2) killing the Lernean hydra (though this looks more like infant Hercules strangling snakes–a different story),

(3) bringing the hind of Ceryneia to king Eurystheus,[?]

(4) bringing the Erymanthian boar to Eurystheus alive, [?]

(5) cleaning the Augean stables [guessing: about to open path for rivers?],

(6) driving away the Stymphalian birds (helped with clackers made by Hephaistos, Hercules flushed the birds out of their hiding place, then shot them),

(7) defeating the Cretan bull by wrestling him to the ground,

(8) capturing the man-eating horses of Diomedes, [?]

(9) acquiring the belt of the Amazon queen, Hippolyte, [total guess]

(10) driving to Eurystheus the cattle of Geryon,

(11) bringing Eurystheus the golden apples of Zeus,

(12) kidnapping Cerberus.

Two of the images have been destroyed, and you can see I’m guessing on many of the others. (I’d be very happy with a low pass on these attributions: it’s not so easy to see the connection between image and myth.)

Another important mosaic in the same house represents the four seasons, with Jupiter and his lover Ganymede.

Here’s one more map, this one of the central area around the arch, the Basilica and the Capitoline Temple.

The “House of the Knight” contains a mosaic of Bacchus coming upon Ariadne, presumably before he’s fathered six children on her.

Next door we find the house of perhaps the only true Roman in town. The columns in this house exceed the capacity of local craftsmen: those curving lines define a column that would have been made in what is modern-day Italy and imported here to the outskirts of the empire.

Back in the private area of the house, we find another fountain in front of what were likely the family’s bedrooms.

These rooms would have had no windows: the Romans thought night air was dangerous, and to drive out the night air, they would have smoked each room before its inhabitant retired to sleep. Their theory might have been a little off, but their practice would have been very effective in protecting themselves against mosquito-borne malaria.

On to the forum!

This space (through the arches) in front of the major structure of the site, would have been the forum, where politicians would come to give speeches and hand out free wine to rouse the rabble who lived in the district down below the forum.

Even now that rabble-dwelling area feels a little “low” and uncared-for,

even though it includes named houses with mosaics like the one of the Desultor–an acrobat specializing in leaping from one horse to another. (Either the mosaic pictures a victorious acrobat, or else it represents something very different: the comic figure of Silenus. Who knows which?)

The large open space of the basilicum would have been the place where taxes were collected. Since taxes were paid in kind (sheep, grain, olives, oil), the government needed a large space in which to gather these goods. As Christianity grew in importance, and the imperial governing structures began to decay, the church took over this space: the “basilica” of a cathedral is a direct descendant of this tax-gathering space of the Roman empire. Evidence of Christian usage can be seen in the low semi-circular baptismal font, now overgrown:

I’ll include below the hypothetical evolution of the monumental center even though neither Zoë nor I could quite map it onto the visible remains of the site. Perhaps you’ll do better.

To the southwest of the basilicum, the temple of Jupiter (Minerva, Juno) overlooks all. Standing on the platform above the monumental steps, we have an overview of the basilicum and what I take to be the place of sacrifice in the middle of the square.

One can imagine impressive effects, given the right timing for the position of the sun.

From further down the hillside, the temple and the remains of the basilicum merge into a single ideal nesting spot for the resident storks…

On the sides of the temple square are smaller alcoves where other gods could be worshipped. Evidently, you would buy a small clay plaque with a symbol of what you were requesting and leave that plaque as an offering for the god or goddess of your choice.

Discovery of an offering to Osiris, the Egyptian god, gives a sense of how far people may have traveled to arrive in Walïlï.

Further down the hill is a reconstructed olive press, much like those (reconstructed and still functioning) we saw in Demnate and Ourika.

And at the edge of the site, we find the house of Orpheus and Galen’s baths. Here, it may be helpful to have both a map of the house and a cross-section to show how the baths worked.

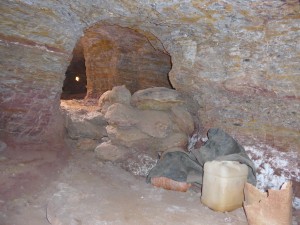

The laconicum was a dry heated room, designed for sweating. The caldarium was a room with a hot plunge bath. The tepidarium was the “warm room,” with pleasing radiant heat. All of these were heated by steam in the walls and underfoot: the famous Roman hypocaust.

And here’s what the remains of that system looks like at Walïlï:

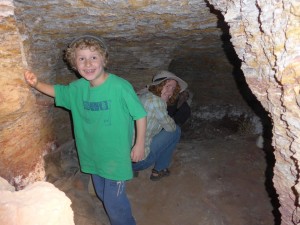

In this last picture, James is in the hypocaust; Jeremy is in the heated space above.

The mosaic of Orpheus appears in the triclinium or the formal dining room:

The colors here seem especially vibrant to me, even given the harsh sunlight.

The colors here seem especially vibrant to me, even given the harsh sunlight.

Here ends the formal tour. But I’d like to put in a quick word for the amazing wildflowers we’ve watched developing all spring. March brought a different palette than February.

And April had its own ideas:

For what it’s worth, when I asked a Moroccan (carrying a load of biomass designed for fodder up the Decumanus Maximus) what was the flower that gave Walïlï its name, he pulled up a morning glory (the last flower above) to show me. But the UNESCO World Heritage site specifies oleander as oualilt instead:

In any case, this region of Zerhoun is a biodiversity hotspot, rightly celebrated for the range of plants and animals it supports, as the young macaque at the entrance to Walïlï seems to remind us.

According to Derek Workman, during the Roman’s two hundred year occupation, “not only was Volubilis one of the gems of the Roman Empire in North Africa but it was also the site of a major ecological disaster. Vast swathes of forests were cleared to create space to grow the enormous quantity of wheat needed to meet the annona, the free grain allowance that was every Roman citizen’s basic right, while the hunting of wild animals for gladiatorial games almost drove indigenous species such as the Atlas Bear and the Barbary Lion into extinction.” [http://www.journeybeyondtravel.com/news/morocco-travel/roman-ruins-volubilis-morocco-2.html]

Still, what remains is beautiful:

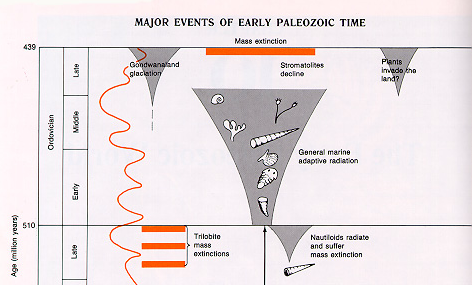

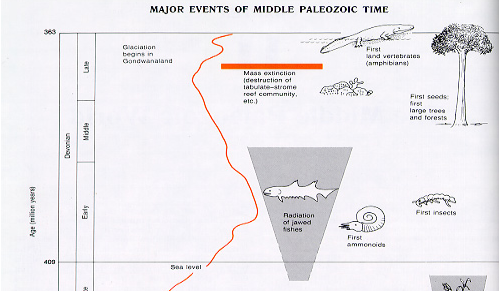

(see earth.usc.edu)

(see earth.usc.edu)

(photo Zoë)

(photo Zoë)

In the black or grey stone, they make me think of shooting stars, as if the residue of this little squid were a path through the stone, light through the darkness.

In the black or grey stone, they make me think of shooting stars, as if the residue of this little squid were a path through the stone, light through the darkness.