Still guided by John Shoup and Eric Ross, we are driving through a dramatic sunset to the zâwiya Sidi Al-Ghâzî to enjoy an evening of Sufi recitation.

The evening will be focused on the religious aspects of the zâwiya or the Sufi brotherhood, but I’m also thinking about the political history of the zâwiya in this region.

In the century after the fall of Sijilmassa (1393), the lack of a strong central government meant that local conflicts proliferated and escalated. In that power vacuum, saints (also called marabouts) and the zâwiyas they founded became an important source of stability: the zâwiyas often provided a physical space in which warring parties could meet to negotiate, and the saints or holy men running the zâwiyas had a powerful influence over local politics. Religiously-motivated donations to the zâwiyas also made them powerful land- and slave-owning institutions.

In a land of uncertain production, spiritual power (baraka) carries a lot of influence. Water is everything–but water comes from God. “Rain or no rain is the realm of God” (Tafilalt villager quoted by Ilahiane).

The Alawite, the royal dynasty that came to power in the seventeenth century and still rules today, rose out of the Tafilalt and derived their political and economic power from their spiritual force (baraka). Back in the 1200s, the citizens of Sijilmassa invited some 1,200 descendents of Muhammed to settle in the city; tradition states that they brought with them the cloak of Muhammed. The Alawite trace their descent from Muhammed through his daughter Fatima and son-in-law Ali: one of their mottos, visible in calligraphy throughout the country, is “Baraka Muhammed.”

Tradition also tells us that the Tafilalt region was plagued with a crippling drought and the inhabitants asked for help. According to one version of the story, the oasis-dwellers sent a message to the governor of Mecca himself, who replied by sending one of his sons to break the drought and rule the oasis, launching the Alawite dynasty. A different version of the story (quoted in Ilahiane) claims that the inhabitants asked the help of an Alawite Sharif or holy man who was headed to Mecca on pilgrimage. He promised to pray for the recovery of the palms and the oasis in exchange for the best stem of dates from each palm. When he returned, the drought was broken and the palms recovered, but the inhabitants refused to give him the agreed-upon reward. The Sharif proclaimed the entire oasis promise-breakers. He told them “tafi bi l’ahd” (honor your promise!) and they replied “la, la, la” (no, no, no): Tafilala or Tafilalet. This version of the story provides a semi-mythical explanation for the difficulties of the region: as promise-breakers, the inhabitants of the oasis and their descendants have been cursed to live in hardship and misery.

The zâwiyas too have fallen on hard times–or perhaps times were always hard. As we drive through the gathering dusk, John tells us that the particular zâwiya we are visiting is grounded in the baraka of the saint Sidi Al-Ghâzî. But three separate villages, all at war with one another, all claimed the saint as their own. The resolution was to divide the body of the saint: one third to each village.

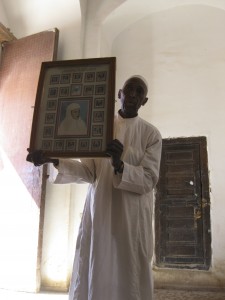

Here, thanks again to Eric and John, are a photo (John) and satellite image (Eric) of the zâwiya Sidi Al-Ghâzî:

The photo is out of date: the minaret has since collapsed. Of the satellite image, Eric notes “The actual shrine (mosque, mausolea, cemetery) in the north part of complex was destroyed by a flood in the late 1960s and is now completely ruined. Members of the Sufi order meet in the Guest House, next to the Shaykh’s house, in the complex’s eastern village. Half of this village too is ruined. The village at the west of the complex contains the shrine of Sidi al-’Arbi al-Ghâzî.”

The photo is out of date: the minaret has since collapsed. Of the satellite image, Eric notes “The actual shrine (mosque, mausolea, cemetery) in the north part of complex was destroyed by a flood in the late 1960s and is now completely ruined. Members of the Sufi order meet in the Guest House, next to the Shaykh’s house, in the complex’s eastern village. Half of this village too is ruined. The village at the west of the complex contains the shrine of Sidi al-’Arbi al-Ghâzî.”

We almost didn’t make it to the zâwiya: the piste was suddenly blocked by a pile of gravel, but the off-road edges were firm enough to take the busses.

Once there, we were welcomed with cushioned seats, ritual hand-washing, cups of tea and peanuts. Zoë sat in the place once occupied by Hassan II.

As we spoke with Sidi Mustafa al-Ghâzî, the muqqadam or leader of the zâwiya, about Sufi practices, he (and later his son) came around sprinkling us with orange-blossom water from this container. That felt an unmistakeable blessing: such a lovely scent!

“Can women be Sufis?” we wanted to know. (John had told us that for the purposes of this evening, we would all be considered “honorary men.” No women would appear though they would have cooked the dinner for us; if the women of the community wanted a look at us, they would peek in through the opening in the roof–and it would be rude to stare at any woman who was looking in at the roof.)

“Oh, yes! A very important early Sufi was a woman,” Sidi Mustafa replied. (Rabi’a al-Adawiyya, 717-801 A.D.) Eric confirms the existence of women Sufis: “In fact, I was once honored to be included as an honorary woman at a gathering of women Sufis in Senegal.”

I don’t quite have the chutzpah to ask how one would cross the gap between the invisible cooking women and these female Sufis. If a daughter of this community wanted to follow the Sufi way, how would that desire be accomodated? Or would it?

The best question of the night: “What’s the hardest thing about following the Sufi way?”

Reply: “Doing what the master tells you to do. Accepting that guidance.”

After several refills of tea and a dinner consisting of medfouna (a savory stuffed bread), bread and heaping platters of chicken for non-vegetarians, we move from discussion to recitation of the Qu’ran and of Sufi poetry. After the recitation (which to uneducated ears sounds very musical) comes songs, accompanied by drumming.

We loved the joy on the face of the muqaddam’s son, holding the hand drum in the photo above. The young man below, a teacher in the local schools, did a soulful solo and eventually stood up to “dance”–this was a bouncing straight up and down, arms swinging out to the sides in a relaxed way, with some turning in a circular motion.

As John had stressed before our arrival, the entire evening was carefully controlled by the muqaddam, whose drumming, voice, and non-verbal cues set the pace for every step of the evening.

Sufism in Morocco is sometimes associated with extreme ritual action, such as the self-mutilation of the Hamadsha, as detailed by Edith Wharton with a mix of gory fascination and cynicism:

At first these stripes and stains suggested only a gaudy ritual ornament like the pattern on the drums; then one saw that the paint, or whatever it was, kept dripping down from the whirling caftans and forming fresh pools among the stones; that as one of the pools dried up another formed, redder and more glistening, and that these pools were fed from great gashes which the dancers hacked in their own skulls and breasts with hatchets and sharpened stones. […] Gradually, however, it became evident that many of the dancers simply rocked and howled, without hacking themselves, and that most of the bleeding skulls and breasts belonged to negroes. […] Hamadch, it appears, had a faithful slave, who, when his master died, killed himself in despair, and the self-inflicted wounds of the brotherhood are supposed to symbolize the slave’s suicide. [… This account] enables the devotees to divide their ritual duties into two classes, the devotions of the free men being addressed to the saint who died in his bed, which the slaves belong to the slave, and must therefore simulate his horrid end.

Vincent Crapanzano offered a more nuanced psychological (or psychiatric) analysis of these rites of self-mutilation in the 1980s (The Hamadsha: a Study in Moroccan Ethnopsychiatry), but in any case, it’s hard to imagine anything further from the delightful devotions so graciously shared with us this evening. We felt tremendously honored to be included in the evening, allowed a glimpse of faith in action.

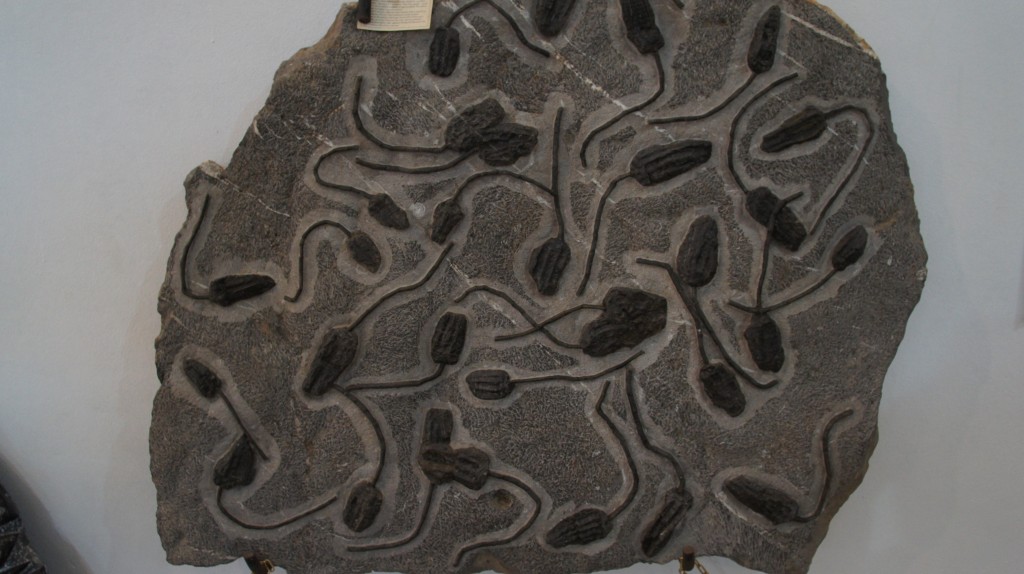

There you are, driving through the desert, and you see a bunch of enormous anthills. Really? Ant-hills? Maybe mole hills? How big are those moles? The size of camels?

There you are, driving through the desert, and you see a bunch of enormous anthills. Really? Ant-hills? Maybe mole hills? How big are those moles? The size of camels?

What’s visible on the surface are merely the waste piles: the heaps of sand and scree dug out of the water channel and removed to the surface of the earth.

What’s visible on the surface are merely the waste piles: the heaps of sand and scree dug out of the water channel and removed to the surface of the earth.

Area of heavy resistance to the French

Area of heavy resistance to the French

What remains of Sijilmassa today are actually the ruins of a mosque built in the 1600s and 1700s by the Alawite dynasty. These are atmospheric if somewhat misleading: I spent ages imagining (incorrectly) thousands of camels parading through these walls.

What remains of Sijilmassa today are actually the ruins of a mosque built in the 1600s and 1700s by the Alawite dynasty. These are atmospheric if somewhat misleading: I spent ages imagining (incorrectly) thousands of camels parading through these walls.

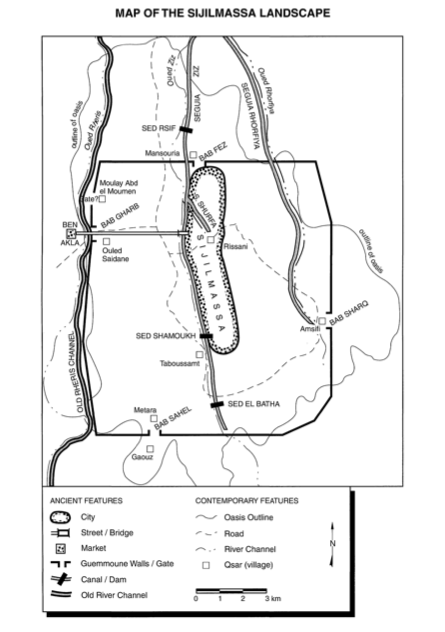

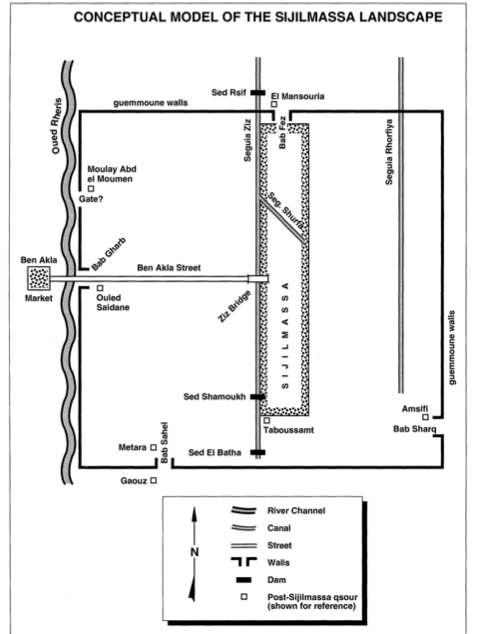

(Image from Lightfoot & Miller, 1996)

(Image from Lightfoot & Miller, 1996)